Zinc squeeze worsens as a second European smelter closes

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

The year has not gotten off to a good start for European zinc buyers.

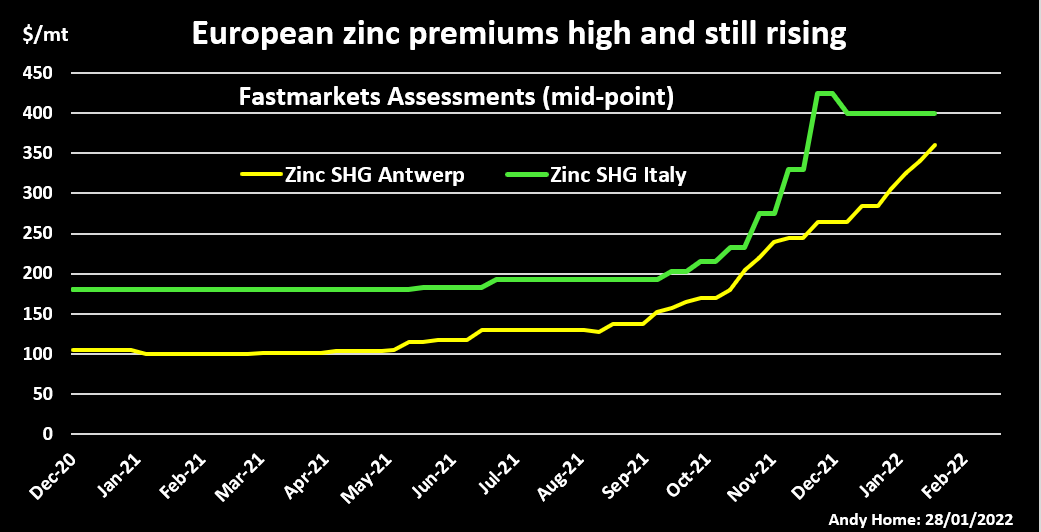

Premiums for physical zinc are at record highs as the market scrambles for metal after the closure of a second zinc smelter due to high power costs.

Nyrstar is placing its Auby smelter in France on care and maintenance, citing “historically high” European electricity prices which show no signs of abating.

Glencore has already closed its Portovesme zinc plant for the same reason.

The unexpected curtailment of the two plants has blown a 260,000-tonne hole in the European zinc supply chain.

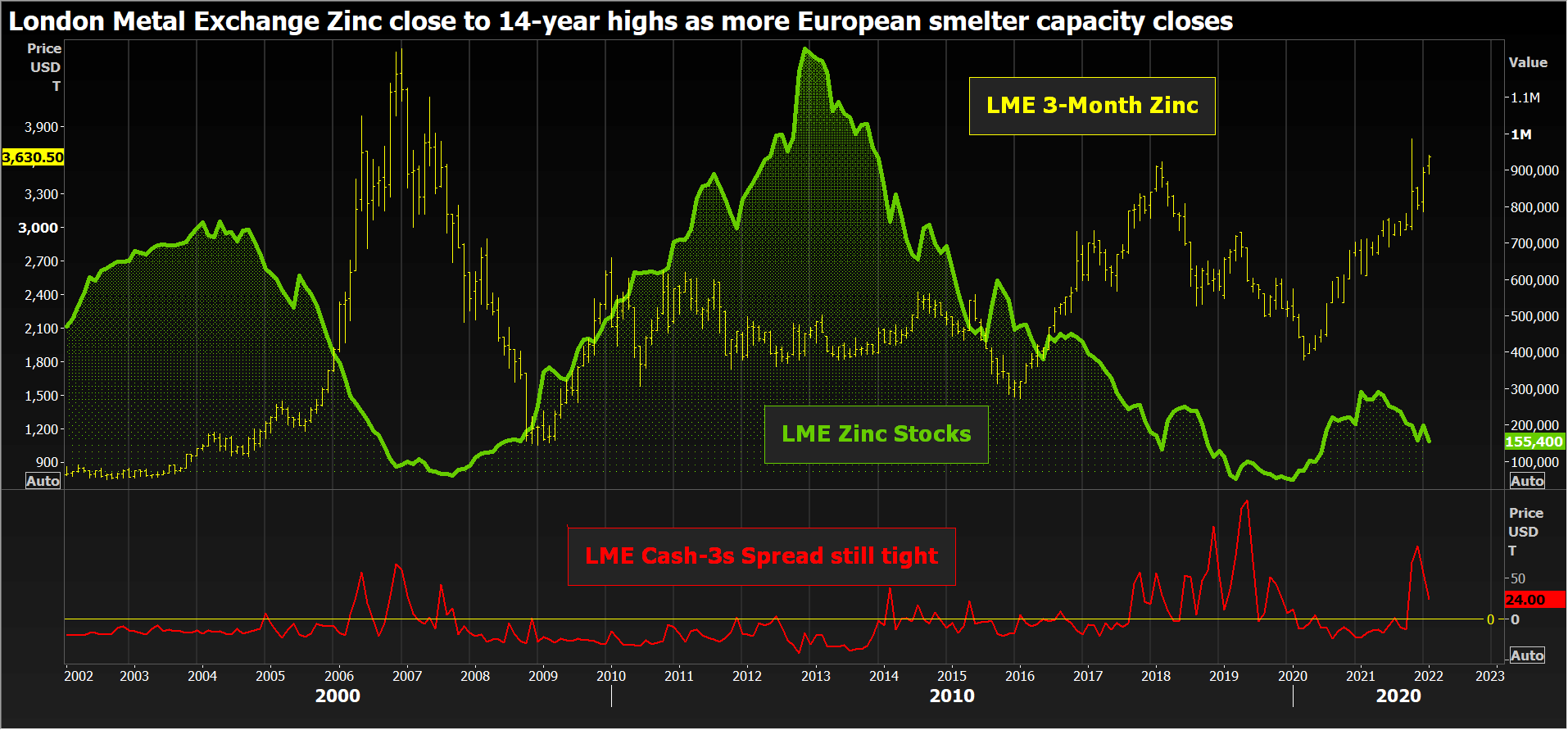

It has also galvanized the London Metal Exchange (LME) zinc price, which is creeping back up towards October’s decade highs with time-spreads still tense.

Europe squeezed

Premiums for physical zinc in Antwerp and Rotterdam have doubled since last October to $320-380 per tonne over the LME cash price.

The cost of getting hold of spot zinc in Northern Europe has now surpassed the previous peak dating back to 2005, according to Fastmarkets which assesses the premiums.

Southern European buyers are paying yet more, although the Italian premium has stopped rising and is now holding steady at $380-420 per tonne.

Europe’s power crisis and the resulting hit on regional zinc smelters has happened so fast it has completely wrong-footed the market.

Low stocks have left European buyers particularly exposed.

LME warehouses across Europe hold just 1,350 tonnes of zinc, split between 1,325 tonnes at the Spanish port of Bilbao and 25 tonnes at the Dutch port of Vlissingen. Only 50 tonnes is actually available, the rest awaiting physical load-out.

LME registered stocks in the United States are higher at over 33,000 tonnes but that hasn’t stopped local premiums rising in sympathy with Europe. Fastmarkets has just lifted its assessment of the Midwest premium for 18-23 cents per lb to 20-24 cents.

It’s a rational price reaction, given both regions will now be competing for imports.

Asian abundance

The extra metal will have to come from Asia, which in stark contrast to the West seems to have plenty of spare zinc.

Most of the zinc sitting in LME warehouses is located at Asian ports, particularly Singapore, which holds 82,050 tonnes, and South Korea’s Port Klang, which holds 30,950 tonnes.

Zinc inventory in China is also rising as the Lunar New Year holiday slowdown is compounded by weakness in the construction sector, a key user of zinc in the form of galvanised steel.

Shanghai Futures Exchange stocks jumped another 23% this week to 92,333 tonnes, the highest level since May last year.

There is potential for an arbitrage-induced flow of Chinese exports to fill the West’s growing supply-chain gap.

However, the lead market should serve as warning that stocks redistribution can be a slow process against a backdrop of continued port disruption and high freight rates.

The global lead market spent most of last year polarised between high stocks in China and shortfall everywhere else. Despite an open arbitrage window, refined lead only started leaving Chinese ports in the fourth quarter of the year.

Fluctuating fortunes

While stocks may take time to shift out of Asia, buyers everywhere else are left trying to gauge a constantly fluctuating power price picture.

Nyrstar had already warned it was reducing production at its European smelters even before the Auby announcement. Like other zinc operators it has likely been trying to reduce amperage around peak usage times.

The impact of such load-adjusting across Europe is difficult to assess but it’s possible there may be a greater loss of metal supply than implied by the two confirmed smelter closures.

It all depends on spot power markets, which are experiencing unprecedented volatility.

The future power price outlook is equally uncertain.

Everyone is assuming that Portovesme and Auby will return once Europe emerges from winter and power prices dip into the warmer summer months.

But what happens next winter? Or the winter after that?

The rolling European power crisis has revealed structural problems in the region’s energy mix which will only become more acute as the bloc moves down the decarbonisation pathway.

Perilous position

This is a big problem for Europe’s zinc smelters.

Even the combination of higher LME price and record high premiums isn’t enough to compensate for the scale of the power cost rise, according to Macquarie Bank.

An analysis of costs for a smelter in the Netherlands reveals it managed break-even across 2021 as a whole but cash margins “are now firmly into negative territory,” Macquarie said. (“Zinc: Higher prices and premiums cannot compensate for higher power costs,” Jan. 6, 2022)

Even if the LME zinc price rose to $4,000 per tonne, a zinc smelter would need a breakeven power price of $157 per MWh, which is still well below both the one month forward and one year forward prices for the Netherlands, Italy and Spain, the bank added.

The LME zinc price almost got there last October, three-month metal hitting a 14-year high of $3,944 per tonne when Glencore and Nyrstar first raised the alarm over rising energy costs in Europe.

The subsequent slide back to the $3,100 level in December was down to market scepticism that the impact on metal supply would be significant.

But the closure first of Portovesme and now Auby leaves no doubt about the perilous cost position of Europe’s zinc smelter sector.

Which is why the LME zinc price is now marching higher again, last trading just above the $3,600 level, and why cash metal is still commanding a premium of $25.

Europe’s zinc buyers can only hope warmer spring weather comes early this year.

(Editing by David Evans)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments