World’s copper mines struggling with covid-19

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters)

The deadly coronavirus has taken a heavy toll on the world’s copper mines.

Output in key producer countries such as Peru cratered over the second quarter of 2020 as lockdowns and quarantine measures caused many mines drastically to reduce operations.

Recovery has been patchy. Peruvian mines had just about returned to normal run-rates by October, but output in Chile, the world’s largest copper producer, started sliding in the third quarter after a robust first half of the year.

Global mine output in the first 10 months of 2020 was still 0.5% lower than 2019 levels, according to the International Copper Study Group (ICSG).

What was supposed to be a year of mined supply growth turned out to be the second consecutive year of zero growth.

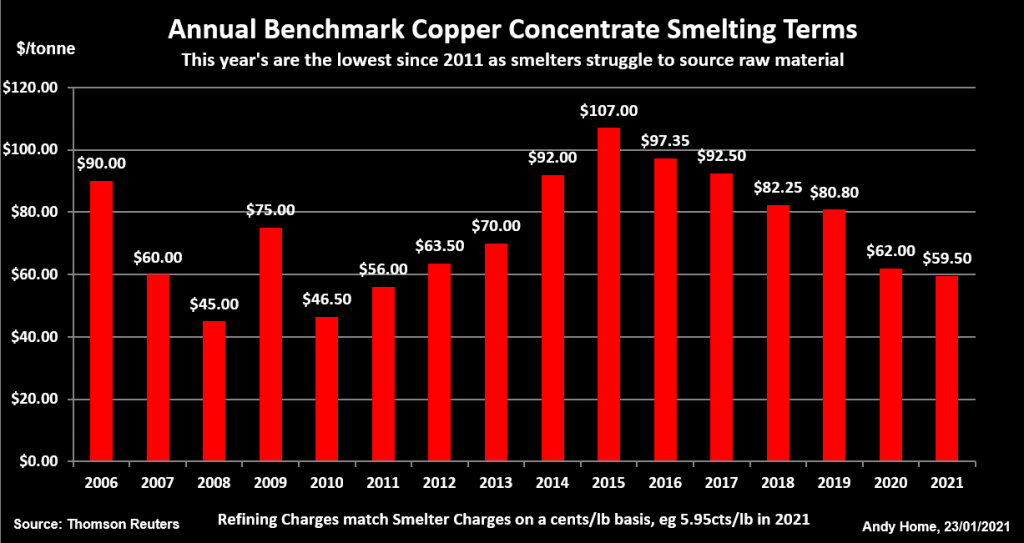

The resulting supply chain stress is manifest in this year’s benchmark smelter terms which are the lowest in a decade.

The message is clear. There’s not enough concentrate to go around

There is as yet no sign of a turnaround in the raw materials segment of the copper supply chain, suggesting full covid-19 recovery could be a protracted affair.

Falling benchmark

Treatment and refining charges, which are what a smelter levies for processing copper concentrates into refined metal, are the best indicator of what is going on in the opaque raw materials market.

And the message is clear. There’s not enough concentrate to go around.

The benchmark terms for this year’s shipments fell to $59.50 per tonne and 5.95 cents per pound from what was already a lowball $62.00 and 6.2 cents in 2019. They haven’t been this low since 2011, another year of mine supply stress, when they were settled at $56.00 and 5.6 cents.

Last year’s supply woes coincided with increased appetite in China as new smelters entered the competition for raw materials.

That should have translated into more concentrates imports. But after increases of 14% and 12% in 2018 and 2019 respectively, imports were down by 1% over the first 11 months of 2020 as smelters struggled to source material.

Output in Chile, the world’s largest copper producer, started sliding in the third quarter after a robust first half of the year

Unless there was a big rebound in December itself, 2020 could be the first year of lower concentrates arrivals since 2011.

An unofficial ban on Australian material hasn’t helped. Strained bilateral relations between Australia and China have impacted Chinese purchases of copper concentrates, which fell to zero in December.

However, Australia was only the fifth-largest supplier to China in 2019 and although constricted trade has exacerbated the tightness, the root cause has been covid-19 disruption, particularly in Peru.

What is normally China’s second top supplier after Chile saw mined copper production contract by 38% over April and May and by 14.5% over the January-October period, according to the ICSG.

Smelter squeeze

There is no sign of any short-term alleviation of the squeeze on smelter margins.

Indeed, it may be getting worse.

China’s Smelter Purchase Team, a grouping of some of the country’s biggest players, has lowered its floor purchase terms to $53.00 and 5.3 cents for the first quarter.

The Team has considerable negotiating muscle and its quarterly minimum terms are a strong signal as to the state of play in the concentrates market.

This quarter’s floor terms are down from $58.00 and 5.8 cents in the fourth quarter and from $67.00 and 6.7 cents in the first quarter of 2020.

Even this low first-quarter floor may be on the optimistic side, since Fastmarkets is assessing the spot market for copper concentrates at below $50.00 and 5 cents.

Quite evidently, copper mine production still has a way to go before satisfying smelter demand.

Long recovery?

Supply should improve as mine activity normalises along with everything else in the wake of covid-19 vaccination programs.

Although Las Bambas like other mines has learned to live with covid-19, it has done so at the cost of deferring expansion work

The ICSG’s October forecast was for world mined copper production to fall by 1.5% in 2020 but to come roaring back with 4.6% growth in 2021.

Things, however, may not be that simple.

Consider the case of the Las Bambas mine in Peru. Production last year was 311,000 tonnes of copper in concentrate, according to mine operator MMG Ltd.

The mine took a 70,000-tonne hit from a combination of COVID-19 restrictions on personnel, unplanned maintenance and, to a lesser degree, community road blockages.

Production recovered to pre-pandemic rates in the fourth quarter with onsite workforce levels “now in excess of 90% of normal, with expanded COVID safe accommodation options available at site and in local communities,” MMG said,

But last year’s disruption will have a long tail.

It was supposed to be “a year of transition for Las Bambas, with an intended focus on continuing to increase mining volumes to open up additional operating faces, completion of the third ball mill and the development of the (new) Chalcobamba pit.”

Most of that activity will now fall into this year “with a return to higher production volumes in following years,” according to MMG. Production in 2021 is expected to come in close to 2020 levels at 310,000-330,000 tonnes of contained copper before rising to 400,000 tonnes in subsequent years.

Although Las Bambas like other mines has learned to live with COVID-19, it has done so at the cost of deferring expansion work.

Long covid-19

When copper smelter terms were last this low – 2010 and 2011 – the copper price was at record highs.

That was no coincidence. The world’s miners were collectively blindsided by the strength of China’s demand for industrial metals. Their inability to respond saw tightness in the concentrates segment of the supply chain transmitted into the refined metal section.

With Chinese demand again booming and analysts looking for a strong pick-up in demand from the rest of the world on the back of “green” technology roll-out, copper mine supply needs to react.

However, if Las Bambas is indicative of operational stresses in the rest of the sector, production is not going to miraculously snap back to pre-pandemic levels this year.

Just as the world starts to consider the effects of “long COVID-19” on human health, the copper market needs to start doing the same for mine supply.

(Editing by David Evans)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments