World needs Congo copper to kick fossil fuels, Friedland says

An African nation emerging from decades of conflict and corruption holds the key to greening the global economy.

That’s the view of mining magnate Robert Friedland, whose Kamoa-Kakula venture just started producing copper in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. After scouring 59 countries over more than three decades, the Canadian billionaire says Congo has the world’s best deposits of the metal used in everything from electric cars to solar panels and power grids.

Governments and companies are embracing electrification to wean the world off fossil fuels, but shortages of metals loom as a major bottleneck unless miners can crank up output at an unprecedented rate. Congolese deposits are taking the spotlight as growth in top supplier Chile slows amid deteriorating ore quality and huge investment burdens.

“If we came from Mars and we were sent in our flying saucer to orbit the Earth to find copper, we would definitely go to Katanga in the southern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo as the richest place on the planet for copper,” Friedland said in an interview.

While geologists have long known about Congo’s potential, exploration and extraction have been hampered by political instability and a lack of transparency and infrastructure.

“If we came from Mars and we were sent in our flying saucer to orbit the Earth to find copper, we would definitely go to Katanga in the southern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo as the richest place on the planet”

Robert Friedland

Some deterrents linger. The need for power in particular is holding back development, said Paul Mabolia Yenga, head of the planning agency at Congo’s mining ministry. While the largest miners are building or renovating hydroelectric plants, dirty diesel generators are still the norm at many sites.

Legal security is also still an issue in the central African nation, with producers having to negotiate waivers on a ban on semi-processed copper exports. Companies including Glencore Plc, which runs two large copper and cobalt mines in Congo, have been pressing to amend a mining code that was revised in 2018 to boost the country’s share of industry profits.

Friedland’s Ivanhoe Mines Ltd. is comfortable operating in Congo and “certain” of being able to ship concentrates until it builds a smelter, he said. The company’s founder and executive co-chairman — who made his fortune from a Canadian nickel project and was behind a massive copper-gold discovery in Mongolia — wants to turn the new DRC mine into one of the world’s largest and greenest.

With a nascent energy transformation making copper the new oil, he likens Congo to Saudi Arabia in the 1950s when the giant Ghawar oil field started. With a government focused on fighting corruption and poverty, money from China, the Middle East and Europe is coming in to a nation whose young, skilled population is anxious to lift up the country, Friedland said.

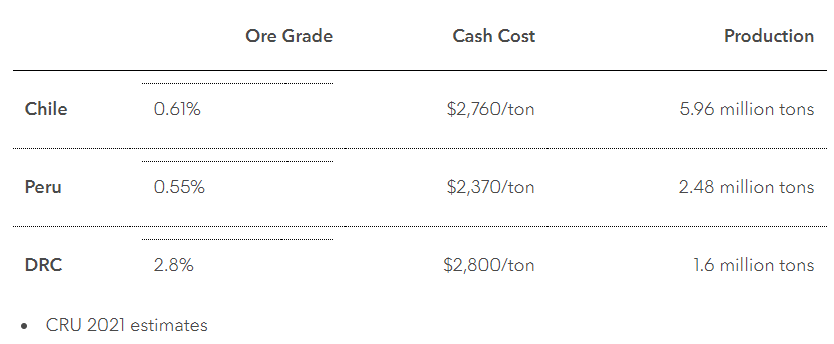

While more established copper jurisdictions such as Chile and Peru still command a greater share of mining investment, project development is accelerating faster in Congo, according to CRU Group.

“It’s not that the DRC has really reduced its country risk dramatically,” Erik Heimlich, a Santiago-based copper analyst with the research firm. “Everywhere is becoming more complicated to develop projects so by comparison they look better.”

The enormous task of meeting supercharged copper demand in the coming decades means developing more of Congo’s mineral potential will be just a part of the solution. CRU estimates the industry will need to commit an additional $100 billion to fill a supply gap of 5.9 million tons by 2031.

“The industry must reinvent itself to gain the trust and participation of host nations, investors and the broader community to sustainably produce enough conductive metals for electrification”

Robert Friedland

Copper supply growth in the 1990s and 2000s was centered around Latin America’s porphyry deposits mined at giant open pits like BHP Group’s Escondida in Chile. The tide is turning against such deposits as declining ore quality and the need to de-carbonize operations expose how much power and water mines use, Friedland said. Richer deposits in Congo can run at a much smaller scale using hydro power, limiting their carbon footprint.

“It’s not clear any longer, when global warming gas becomes a central indicia, that Chile is the obvious place to mine,” Friedland said. “Quite the contrary. The obvious place to mine is now the Congo.”

A push by politicians in Chile and Peru to take a bigger share of industry profits also challenges country-risk assumptions as Congo appears to welcome back investors. The presence of BlackRock and Fidelity on Ivanhoe’s shareholder register underscores the transparency of the Vancouver-based company’s Congo operations, he said.

Ivanhoe started churning out concentrates late last month at its Kamoa-Kakula venture with partners Zijin Mining Group Co. and the DRC government. A first phase is set to produce 200,000 tons a year. Eventually output could exceed 800,000 tons given the “ocean” of available mineral, as long as the operation gets enough hydroelectricity.

“Our geologists are very confident that, with continued exploration and given what we know about the district, it could be 10 times bigger than what we see today,” Friedland said.

The discovery and development of such a large deposit by a relatively small company shows Congo’s mineral wealth is still untested and deserves more exploration, he said. “We need scores of discoveries at this scale if we are going to electrify the world economy.”

The industry must reinvent itself to gain the trust and participation of host nations, investors and the broader community to sustainably produce enough conductive metals for electrification, he said.

It’ll be a massive task after a period of low prices saw miners slash budgets to focus on balance sheets and dividends, leading to a dearth of discoveries. Projects are getting trickier and pricier to build and run amid rising environmental and social standards, and there’s general ignorance about where the building blocks of a carbon-neutral world will come from, Friedland said.

“The average person just doesn’t understand the scale of the implication for raw materials,” he said. “If you’re not just green washing, and you really mean it, then it is the revenge of the miners.”

(By James Attwood, Erik Schatzker and Michael J. Kavanagh)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Kimbrough Williford

I will keep my eyes on this subject.