Why the Fed must pivot

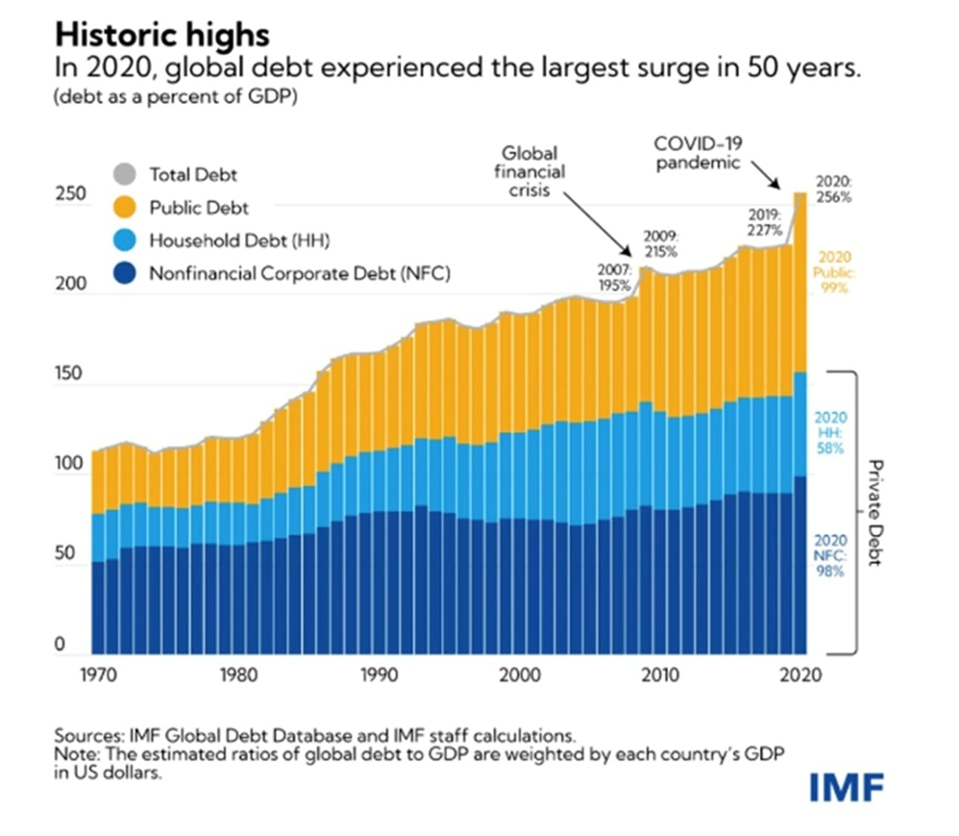

According to the Institute of International Finance (IIF), the value of global debt was slightly below $300 trillion in 2022. The world debt to GDP ratio fell last year but it is still above pre-pandemic levels.

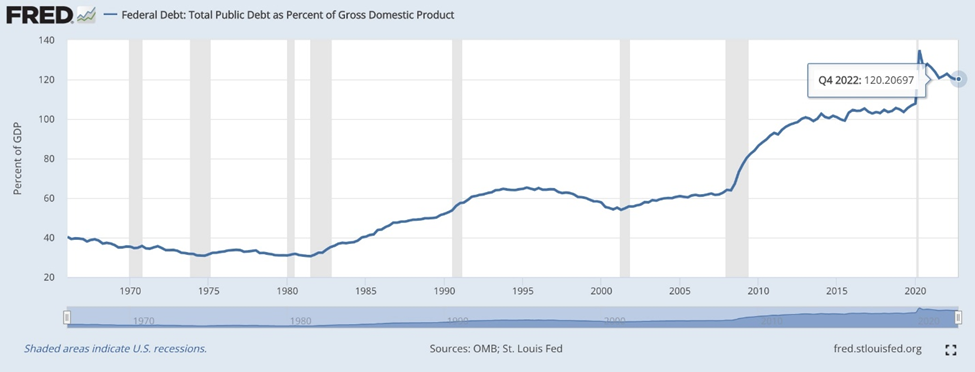

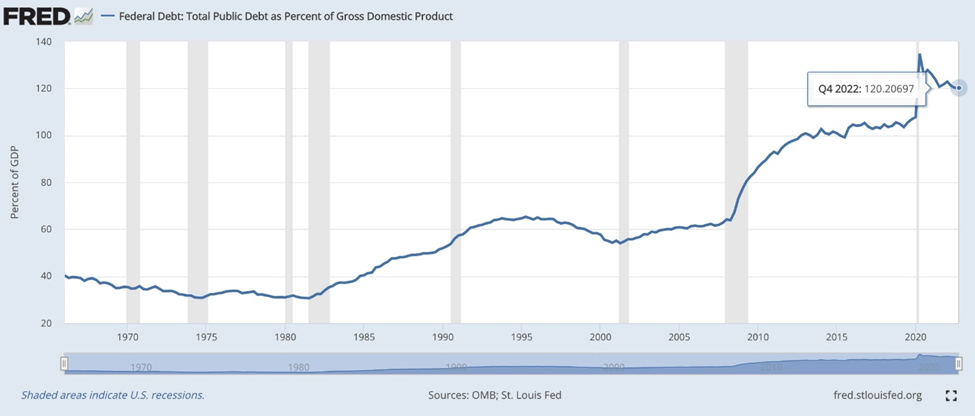

The US debt to GDP ratio in 1982 was around 35%. Today it is more than three times higher, at 120%.

The issuance of European and American high-yield bonds reached a record-high $1.6 trillion in 2021, according to the IMF. A lot of this debt is rolling over at much higher interest rates, pushing pressure on the governments who issued it to pay out the interest when the bonds mature.

Economist Nouriel Roubini believes, and I agree, that the increase in long-term interest rates is leading to massive losses for creditors/banks holding long-duration assets such as 10, 20, 30-year Treasuries. The economy is thus falling into a “debt trap”, and central banks confronting this dilemma will end their monetary tightening/ inflation fight so as to avoid a financial and economic meltdown.

How did we get here? And what’s next for the Fed?

Dash for cash

Investopedia defines a bank run “when a large number of customers of a bank or other financial institution withdraw their deposits at the same time over fears about the bank’s solvency. As more people withdraw their funds, the probability of default increases, which, in turn, can cause more people to withdraw their deposits. In extreme cases, the bank’s reserves may not be sufficient to cover the withdrawals.”

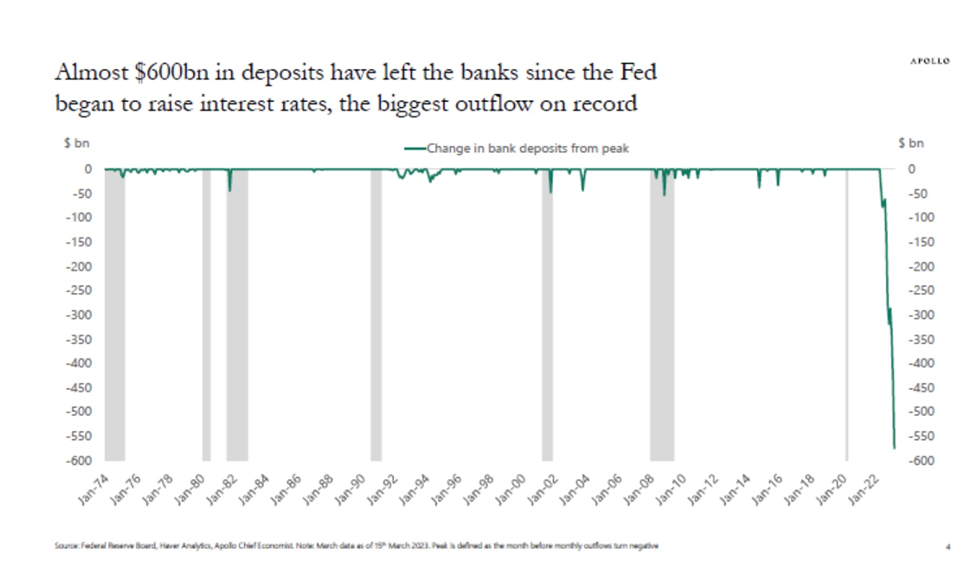

Historically high interest rates have led to the collapse of three US banks — Silicon Valley, Silvergate and Signature — and the Swiss government-assisted rescue of Credit Suisse. Other US regional banks including First Republic, are in distress due to excessive levels of deposit flight.

Indeed investors are piling into cash at their fastest pace since the pandemic, Bloomberg wrote recently, spooked by a series of bank runs while seeking higher interest rates in money-market funds.

According to a report from Bank of America, during the first quarter of 2023 investors dumped $508 billion into cash funds, with more than $100 billion going into the money markets, which pay higher interest.

Data from the Investment Company Institute said money-market funds are now flush with a record $5.2 trillion, with over $300 billion added in the three weeks to March 29.

The Federal Reserve said depositors withdrew $126 billion from US banks during the week ending March 22, with the biggest 25 banks losing $90 billion on a seasonally adjusted basis.

Total industry deposits fell to $17.3 trillion, down 4.4% from the same week a year ago, which is the lowest since 2021. Yahoo Finance notes deposits had been declining even before the SVB failure, down 5% annually in the fourth quarter of 2022.

The article also says ‘The challenge the deposit outflows create for all banks is that if they raise rates on their deposits to keep customers, that could make them less profitable. But if they lose too many customers, as Silicon Valley Bank did, they give up critical funding and may have to sell assets at a loss to cover withdrawals.’

The latter is precisely what happened to Silicon Valley Bank. Customers withdrew $42 billion in one day, leaving the bank with a negative cash balance of $958B, forcing regulators to seize it.

Since then, government and industry officials have been trying to prevent further bank runs, pledging to cover all depositors at the seized banks and promising to help other regional banks. Eleven large banks including JP Morgan Chase, Wells Fargo and BoA provided First Republic with $30B in uninsured deposits to stabilize the situation.

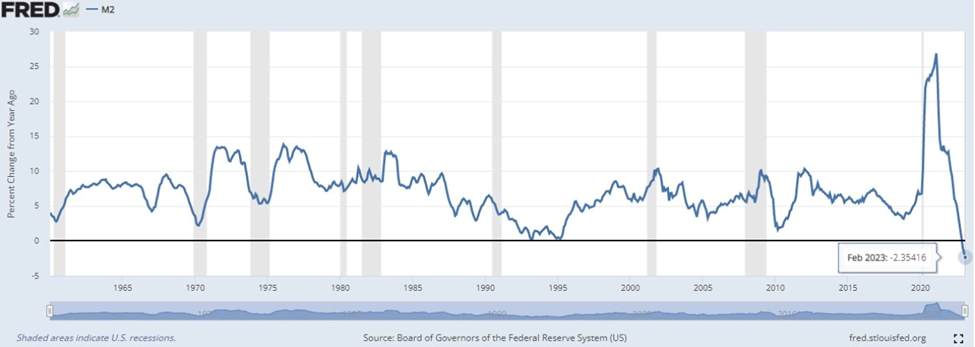

Money supply falling

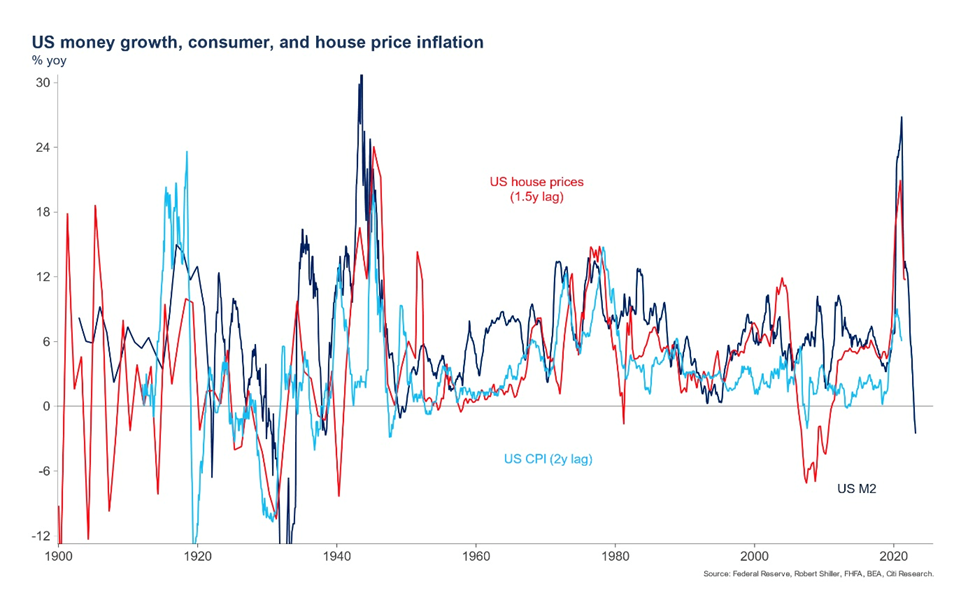

M2 money supply is a measure of how much cash and cash-like assets (e.g. bank deposits, money market funds) is circulating in the US economy. M2 contracted in December for the first time since the 1940s, falling a non-seasonally adjusted 2.2% to $21.099 trillion in February, from the same period a year earlier.

The contraction is due to the US Federal Reserve purposefully unwinding its balance sheet by selling government bonds and other assets, a process known as quantitative tightening, or QT.

The Fed really has only two levers it can push or pull when it comes to monetary policy: interest rates and the money supply. For the past 30 years or so, money supply manipulation has taken a back seat to interest rate hikes or cuts, because the former is seen as less reliable for policymaking. Central banks now typically use interest rates as the primary tool for achieving inflation targets, usually around 2%.

Reuters quotes Matt King at Citi in London, an expert on capital flows and liquidity, saying that the reduction of US money supply is a red flag for the economy and financial markets.

“M2 is a driver of broader asset price inflation, consumer inflation, equities, and real estate. It is sending quite a negative signal for all of those now, and will likely feed through to broader economic weakness,” he said.

The article goes further to state that, all things being equal, it is a sign the Fed has no need to raise interest rates further. Given the lag of one to two years between money supply changes and the impact on asset prices and inflation, it may even be a sign that the U.S. central bank should be cutting rates.

Quantitative destruction

As I’ve said, the Fed knew full well what would happen to banks and themselves if they started raising interest rates.

“Down in the footnotes of the recently released financial statements of the combined Federal Reserve Banks for the second quarter of 2022, we find this startling disclosure: the mark to market loss on June 30 had increased to $720 billion. That’s a number to get your attention, even in these days of counting in billions, especially when compared to the Fed’s reported total capital on the same date of only $42 billion. The Fed’s mark to market or economic loss at the end of the second quarter was thus 17 times its total capital, making it deeply insolvent on a mark to market basis. (Woe to any bank supervised by the Fed which gets itself in the same situation! Oh yes, we know the Fed will earnestly insist that it is different, but that doesn’t change the fact of the market value losses.)”

- The Federalist Society, ‘The Fed’s Mark to Market Loss Approaches $1 trillion, while the write-off of student loans hits $420 billion’, Sept. 28, 2022

The situation since last June has only gotten worse. The Federalist Society estimates the Fed’s market value loss in its investment portfolio during the third quarter increased by $275 billion, bringing total losses to about $995B. Considering the Fed raised the federal funds rate 25 basis points to 4.75-5% in March, pushing borrowing costs to the highest since 2007, Fed losses have probably surpassed $1 trillion.

Remember, these are only “paper losses”. Until the Fed actually sells them, they only exist as an accounting entry. But, as the Federalist Society notes, even if the Fed never sells any of its underwater bonds and mortgage-backed securities, it must finance its long-term fixed rate assets with floating rate liabilities at ever-higher interest rates.

The Fed knew that by hiking interest rates, it would crater the value of its own vast investment portfolio. What it may not have foreseen is the damage higher rates are doing to the greater financial system.

A recent Financial Times article states the recent spate of bank failures is a symptom of “quantitative destruction”. This is what happens when the institutional structures that thrived in a decade of near-zero interest rates and easy liquidity are suddenly replaced by the largest and fastest interest rate hikes in 40 years, combined with central bank balance sheet reductions (QT).

Here’s how it works: during the easy-money years of QE, liquidity was plentiful and companies could easily access debt and equity markets. This becomes harder as rates rise and liquidity evaporates. The danger comes when asset owners have to sell publicly listed assets so they can re-invest in funds they have committed to.

This is precisely what happened during the UK pension fund crisis. In September 2022, a series of interest rate increases exposed vulnerabilities in liability-driven investment funds (LDIs) held by UK pension schemes. A number of pension funds were hours from collapse when the Bank of England rescued them by intervening in the long-dated bond market.

These “gilts” are used by LDIs s as collateral to raise cash.

But as CNBC describes, LDIs were forced to sell gilts, which in turn pushed down prices. This sent the value of their assets below that of their liabilities, meaning the pension funds holding them risked falling into insolvency.

A New York Federal Reserve Board paper cited by the FT highlighted how these kind of asset fire sales by non-bank financial institutions — which now account for $60tn of global assets — could inject systemic risk back into the banking system.

Stagflationary debt crisis looms

Nouriel Roubini, the economist who famously predicted the 2008 financial crisis, says that banking-sector stress makes a stagflationary debt crisis more likely and potentially more severe.

Writing for Project Syndicate, “Dr. Doom” starts crafting his argument with an observation about “duration risk”. Higher inflation leads to higher bond yields because investors demand a better return on investment due to inflation. However, this also means a decline in bond prices, since yields and prices move in opposite directions.

“As rising inflation in 2022 led to higher bond yields, 10-year Treasurys lost more value (-20%) than the S&P 500 (-15%), and anyone with long-duration fixed-income assets denominated in U.S. dollars or euros was left holding the bag,” Roubini writes, arguing that:

“The consequences for these investors have been severe. By the end of 2022, U.S. banks’ unrealized losses on securities had reached $620 billion, about 28% of their total capital ($2.2 trillion).”

“Making matters worse, higher interest rates have reduced the market value of banks’ other assets as well… Accounting for this implies that U.S. banks’ unrealized losses actually amount to $1.75 trillion, or 80% of their capital.”

And then there’s this:

“[M]ost U.S. banks are technically near insolvency, and hundreds are already fully insolvent.”(again, this is “on paper”. The current regulatory regime allows banks to value securities and loans at their book value rather than their market value)

Where the rubber hits the road, so to speak, is what happens when depositors start withdrawing their money.

Deposit franchise refers to an asset that is not on a bank’s balance sheet. By some estimates rising interest rates have increased US banks’ total deposit-franchise value by about $1.75 trillion.

“But this asset exists only if deposits remain with banks as rates rise, and we now know from Silicon Valley Bank and the experience of other U.S. regional banks that such stickiness is far from assured,” Roubini writes.

“If depositors flee, the deposit franchise evaporates, and the unrealized losses on securities become realized as banks sell them to meet withdrawal demands. Bankruptcy then becomes unavoidable.”

Now consider the effects of this on the broader economy. Roubini says The credit crunch caused by today’s banking stress will create a harder landing for the U.S. economy, owing to the key role that regional banks play in financing small- and medium-size enterprises and households.

Not only are borrowers facing higher interest rates, the increase in long-term rates is also, as mentioned, leading to massive losses for creditors holding long-duration assets such as US Treasuries. This will result in the economy falling into a “debt trap”.

We’ve heard this from Roubini before. Last fall, the economist made headlines for his views on global debt, which, when combined with the coming stagflation, set up a “stagflationary debt crisis”. What would this look like? Stagflation is what happens when low economic growth is combined with high inflation.

The first thing to understand, is this stagflationary period differs from that of the late 1970s/ early 1980s, due to the much higher debt levels.

According to the FRED chart below, the US debt to GDP ratio in the ‘70s was around 35%. Today it has more than tripled, at 120%.

This severely limits how much and how quickly the Fed can raise interest rates, due to the amount of interest that the federal government will be forced to pay on its debt.

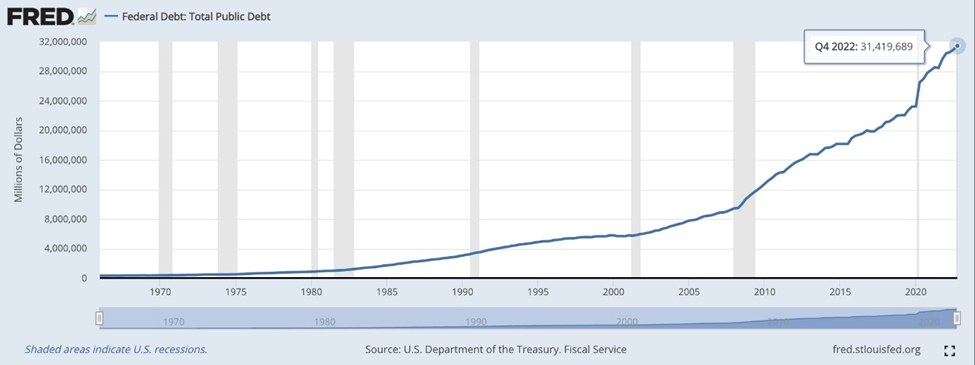

Each interest rate rise means the federal government must spend more on interest. That increase is reflected in the annual budget deficit, which keeps getting added to the national debt, now sitting at a shocking $31.6 trillion.

What will the Fed do?

As for what a banking crisis means for the Fed, Roubini believes that continuing to raise interest rates to fight inflation will fuel systemic debt crisis that liquidity support will be insufficient to resolve.

(After UBS announced it would buy Credit Suisse, the Fed joined other central banks in a coordinated action to provide liquidity through standing US dollar swap line arrangements.)

He maintains that A severe recession is the only thing that can temper price and wage inflation, but it will make the debt crisis more severe, and that in turn will feed back into an even deeper economic downturn. Since liquidity support cannot prevent this systemic doom loop, everyone should be preparing for the coming stagflationary debt crisis.

Other commentators say that, by effectively reducing the money supply, quantitative tightening has amplified the impact of rising rates throughout the economy.

The New York Times’ Jeff Sommer writes that the Fed’s current tightening program hasn’t made much of a dent in its balance sheet, which currently has assets of $8.4 trillion. Continuing at this slow pace of securities sales, it would take two years to reach the $6 trillion range.

The effects of slowing growth, increased unemployment and reduced inflation are hard to calculate, but Solomon Tadesse, the head of North American Quantitative Equity Strategies for Société Générale, estimates that a $2T reduction would be roughly equivalent to adding 2.4 percentage points to the federal funds rate. “It would have a serious impact,” he told Jeff Sommer.

What kind of impact? “If the Fed keeps tightening,” Sommer writes, “it will have to remain a behind-the-scenes giant in the mortgage market for many years — or sell large quantities of securities at a loss. Such sales would risk a new market debacle that could make mortgage rates soar further, adding to the damage in the housing and construction and real estate industries.”

“Of course, the Fed could abandon rate increases and quantitative tightening. That would mean an end to the Fed’s inflation fighting, and was unthinkable a short time ago. But it could happen if banking problems escalate and a recession is evident.”

Conclusion

The Fed’s QT program has contributed to the US regional banking crisis and to the high mortgage rates that have made it difficult for ordinary Americans and Canadians to afford homes.

Silicon Valley Bank failed because it took on too much duration risk, essentially, investing too many deposits in long-term Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, which paid higher interest than short-term securities.

This was fine when interest rates were low, but when they went up quickly and by a lot, bond prices crashed. Over the past year, the US bond market has fallen over 18%, as interest rates rose from 0% to 5%. That kind of rise is unprecedented.

When SVB depositors started withdrawing their cash, the bank had no choice but to sell its long-term bonds at a loss. When news of that hit social media, depositors panicked, triggering a bank run.

How many other small US regional banks are at risk of default?

To paraphrase Warren Buffet, “it’s only when the tide goes out that you can see who’s swimming naked.”

Many American bank customers aren’t taking any chances. During the first quarter of 2023, investors dumped $508 billion into cash funds, with more than $100 billion going into the money markets, which pay higher interest.

According to a report form Bank of America, during Q1 2023 investors dumped $508 billion into cash funds.

Nouriel Roubini says most US banks are technically near insolvency, and hundreds are already fully insolvent.

Could it happen to the Fed?

For the first time ever, last September, it was reported the Fed lost money, almost 3/4 of a trillion dollars on mark to market.

That’s a result of the plummeting prices of the Fed’s government bonds and mortgage-backed securities.

The Fed’s loss at the end of the second quarter was 17 times its total capital, making it deeply insolvent on a mark to market basis. If the Fed was a regional bank it would have been closed and taken over.

Of course, the Fed will never go bust. If it needs to intervene in the bond market, like the Bank of England did, it can just print money to buy government bonds being dumped by failing banks.

But many including myself are increasingly calling for the Fed to pause its inflation-fighting interest rate hikes because of the current banking sector chaos. To be clear, the Fed must pivot; there is no alternative.

Is it any wonder that gold shot to within $50 of its all-time high on Tuesday, breaking $2,000 as the dollar and bond yields fell?

It’s not likely the Fed will raise another .25% May. If they do it’ll be the last raise and they will pause over the summer. The dollar will weaken and precious, industrial and battery metals will soar in price.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments