Why Freeland’s “friend-shoring” is such a bad idea

Chrystia Freeland is Canada’s Deputy Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance. Previously she was the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Many people see her as taking over from Prime Minister Trudeau, whose popularity has waned amid a series of scandals, and the arrogance that comes with winning government for two straight terms.

Last week Freeland was in Washington, D.C. giving a speech to the Brookings Institution about Canada’s role in world affairs. Usually these talks are nothing but hot air so I tune out, but in this case, Freeland had some important things to say, on a subject we have previously written about: friend-shoring.

To summarize, Friedland’s position is that we must abandon the optimism, inherent in globalization, that post-communist countries would gradually turn into healthy democracies and good global citizens.

In her speech, ‘How Democracies Can Shape a Changed Global Economy’, Freeland insisted that we stop supporting autocracies such as Russia and China and focus on trade and investment in the countries of our democratic allies.

Putin’s Russia and Xi’s China have both moved the goalposts far down the field toward autocracy. Both have declared themselves presidents for life, Putin has twice invaded Ukraine and Xi has threatened to attack Taiwan, along with beefing up China’s military and bullying its neighbors in the South China Sea.

China and Russia are the antithesis of democracy, yet we continue to buy their oil and minerals.

But the problem I have with friend-shoring, is its economic costs outweigh any gains that it would bring, politically.

What is friend-shoring?

“Friend-shoring” presumes a world divided between free-market economies and countries that align with authoritarian regimes. First there was “offshoring”, which transferred manufacturing (and jobs) overseas to save money on labor and to maximize profits. Then came “onshoring”, the idea of bringing production home to reduce supply chain disruptions and to repatriate US jobs. Friend-shoring, or ally-shoring, is similar to onshoring except that it’s not restricted to domestic production. Reliable friends are also deemed okay as sources.

The idea is for a group of countries with shared values, and at a similar stage of development, to source raw materials and to manufacture goods, from within that group. The goal is to prevent less like-minded nations from exploiting their comparative advantage, or in some cases, their monopolies, in key raw materials, technologies or products.

“[Countries] that espouse a common set of values on international trade … should trade and get the benefits of trade,” US Treasury Secretary (and former Fed chair) Janet Yellen said earlier this year alongside Freeland at an event by Canada 2020, a think tank. “The idea is to ensure the US and its allies have multiple sources of supply and are not reliant excessively on sourcing critical goods from countries, especially where we have geopolitical concerns.”

According to Freeland, the assumption that the world’s countries could all “get rich together” through trade — the consensus during the 1990s, apexed by China being admitted into the World Trade Organization in 2001 — has proven overly optimistic.

“I really believe that Putin’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has shown us all: it didn’t work,” Freeland said of the world’s attempt to embrace free trade. “That era is over. We need to figure out what replaces it.”

Clearly the target is China and Russia. The US wants to reduce dependence on authoritarian regimes like China that supply the majority of the world’s rare earths and magnets, and dominate the production of several battery/ electrification metals including copper, zinc, tin, lithium and graphite; and diversify away from Russian suppliers of critical commodities such as energy, food and fertilizer. In some cases, like semiconductors, the goal is to divvy up supply between friendly nations. For example the US has recently begun engaging with South Korea to diversify chip production away from Taiwan, which is its no. 1 supplier but faces a security threat from China.

Friend-shoring isn’t just theoretical; the term has made its way into a 250-page report released by the Biden administration, titled ‘Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-Based Growth’.

An example of friend-shoring put into practice, is the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), formed in June as a sort of “metallic NATO”. Members include the United States, Canada, Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the European Commission. Note who is not in the club: China and Russia.

Another example is the section of President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act relating to electric vehicles. A system of tax credits will now apply to vehicles made in Canada (previously only American-made cars would qualify), and also requires that an eligible vehicle’s battery include a percentage of critical minerals procured from countries with which the US has a trade agreement, such as Canada. The measure is destined to curb Chinese dominance in the critical minerals supply chain.

Delivering what some are describing as an obituary for the 33 years of peace and stability between the fall of communism in 1989 and Russia’s violation of Ukrainian sovereignty this past year, Freeland also addressed the notion of “petro-tyrants” like Putin. Ongoing dependence on such leaders in countries like Russia, which are vital suppliers of oil and natural gas, cannot continue, she said, adding:

“As fall turns to winter, Europe is bracing for a cold and bitter lesson in the strategic folly of economic reliance on countries whose political and moral values are inimical to our own.”

Freeland though, raised eyebrows among the business audience when she stated that “Canada must and will show similar generosity in fast-tracking, for example, the energy and mining projects our allies need to heat their homes and to manufacture electric vehicles.”

As CBC News reports, Critics accuse Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his government of dragging their feet on approving energy projects like export terminals for liquid natural gas.

Goldy Hyder, CEO of the Business Council of Canada, so liked Freeland’s speech, that he dubbed it “the Freeland Doctrine”.

“The real test, however, is can Canada convert intentions into actions and be a reliable supplier of much-needed energy and critical minerals,” Hyder said, via the CBC.

“Can Canada expedite projects, as the prime minister has proposed, while providing regulatory predictability to attract the capital to build much-needed infrastructure?” he continued.

“This is what we will ultimately be judged by: can we deliver the goods countries need to be able to live their values by extracting themselves from relying on autocratic oil and gas?”

All good questions. As we have repeatedly stated, it can take up to 20 years for a new mine to be approved in Canada, after all the stakeholders have been consulted and the environmental regulations, that are often duplicated (federally and provincially), are satisfied.

Economic pain

Friend-shoring sounds good, but its harmful effects far outnumber its benefits.

The first criticism is that it risks being exclusionary and elitist, and can lead to protectionism and higher costs.

Friend-shoring runs counter to free-trade principles like comparative advantage, that underpin the current world order. Let’s say I need to source iron blocks. The cheapest place to buy them, and the country that has comparative advantage in iron blocks, is Afghanistan (I don’t know who actually makes the lowest-cost iron blocks, this is just an example). But Afghanistan has a poor human rights record, and is currently ruled by the Taliban, so it doesn’t make my “friends” list.

Instead, I decide to buy them from Luxembourg, not because its iron blocks are the cheapest, but because Luxembourg is part of NATO. Who wins in such an arrangement? Definitely not Joe and Jane Sixpack.

The whole system of world trade could quickly become exclusionary and elitist. By only trading with developed countries, those with high labor standards, for example, citizens will have to pay for those higher standards, and therefore, higher-priced products. Countries would also be tempted to protect their domestic industries, again resulting in higher costs to consumers. This is during a period of rampant inflation.

Friend-shoring forces companies to pick sides and can unintentionally forge bad blood with other countries, one commentary argues.

Friend-shoring is the thin edge of the wedge, of protectionist, anti-globalization measures. A good example is Donald Trump’s trade war with China, which he accused of dumping cheap aluminum and steel into the US market. The penalty was tariffs on hundreds of billions worth of Chinese imports. The war turned into a stalemate because China simply imposed countervailing duties on US imports.

As for Trump’s argument that trade deficits are bad and should be rectified through tariffs, the Cato Institute argues that protectionism in fact cannot cure the trade deficit. If Congress were to implement an “emergency tariff” of 10 to 15%, states a paper on the topic,

American imports would probably decline as intended. But fewer imports would mean fewer dollars flowing into the international currency markets, raising the value of the dollar relative to other currencies. The stronger dollar would make U.S. exports more expensive for foreign consumers and imports more attractive to Americans. Exports would fall and imports would rise until the trade balance matched the savings and investment balance.

Without a change in aggregate levels of savings and investment, the trade deficit would remain largely unaffected. All the new tariff barriers would accomplish would be to reduce the volume of both imports and exports, leaving Americans poorer by depriving them of additional gains from the specialization that accompanies expanding international trade.

Building resilient friend-shoring supply chains comes with high costs, including the steep price tag of relocating manufacturing operations to another hemisphere.

Economists argue that picking trade partners for geopolitical reasons could create a world of antagonistic blocks, similar to George Orwell’s imaginary world in ‘1984’, or the Cold War. As the Wall Street Journal maintains, the global economy could split into two hostile camps, the United States and China, thus hurting growth and accelerating inflation.

The East-West split has already begun.

Russia is attempting to build an alliance of countries, anchored by a common currency, or basket of currencies, in direct opposition to US economic hegemony.

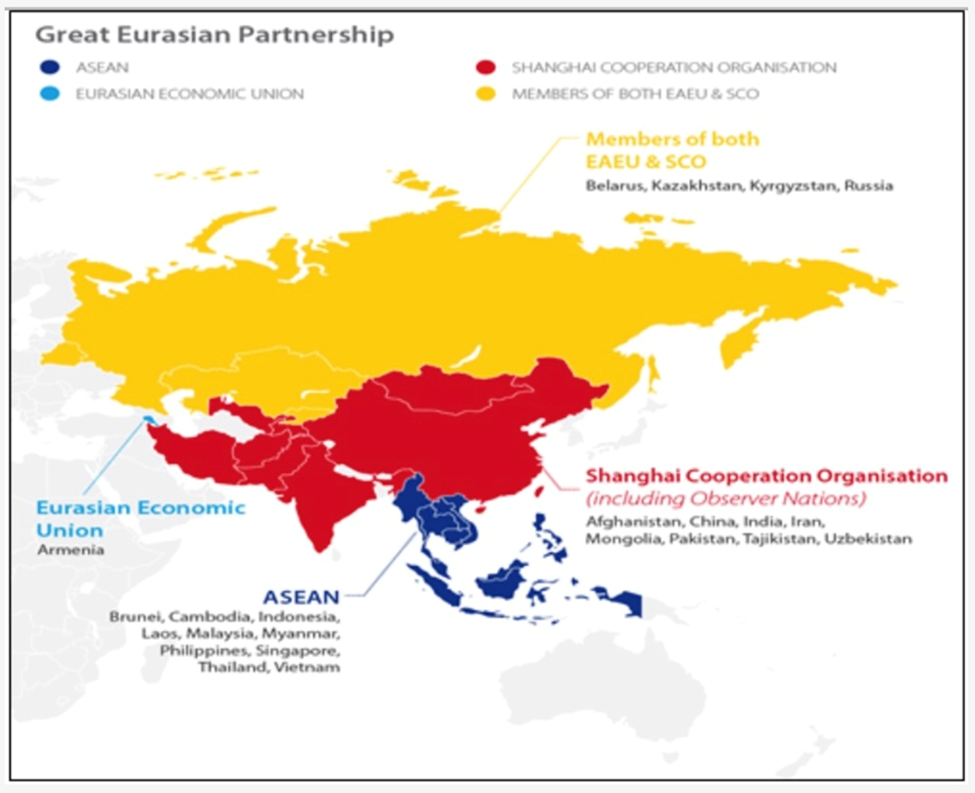

The EAEU refers to the Eurasian Economic Union, comprised of Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. BRICS is the acronym for Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. SCO is a new (2021) grouping consisting of eight member states, China, Russia, India, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, as well as four observer states, Belarus, Iran, Afghanistan, and Mongolia, and a further six dialogue partners, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Cambodia, Nepal and Sri Lanka.

Beijing has been very smart about courting developing countries by offering them financial support in exchange for access to minerals and regional influence. Excluding Mexico, which has a free-trade agreement with the United States and Canada, China is now Latin America’s largest trading partner, according to UN trade data from 2015-21. Consider this alarming statistic: in 2000 China’s trade with Latin America amounted to just $12 billion, but by 2019 it had grown 27.5X to $330 billion. By 2035 trade between China and Latin America/ the Caribbean, is expected to double again, to $700 billion.

Earlier this year, Beijing began promoting its “Global Security Initiative”, an alternative to the US-led security order. As explained by The Financial Times, the initiative is a collection of policy principles such as non-interference and grudges against US “hegemonism”.

Russia and China have both made moves to de-dollarize and set up new platforms for banking transactions outside of SWIFT that skirt US sanctions. The two nations share the same strategy of diversifying their foreign exchange reserves, encouraging more transactions in their own currencies, and reforming the global currency system through the IMF.

The West has also been forming new groupings to counter China and Russia. Last year for example, Australia, the US and the United Kingdom announced the new AUKUS security pact, widely seen as an attempt to strengthen regional military muscle in the face of China’s growing presence off Australia’s western coast.

Beata Javorcik, chief economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, calculates that the creation of a two-bloc world would lead to a 5% loss of global economic output over a 10- to 20-year period — equivalent to roughly $4.4 trillion.

Moreover, economic relationships are considered vital in keeping the peace. Trade-Peace Theory says that close economic interdependence helps to discourage countries from going to war.

The European Economic Community, the precursor to the European Union, began in the 1950s, as a way of tying European countries together through trade, to avoid another world war.

War is also extremely costly.

An attempted invasion, or blockade, of Taiwan would cause a breakdown in trade between China and North America worth hundreds of billions of dollars annually, according to Jia Wang, from the University of Alberta’s China Institute.

The main disadvantage of friend-sourcing though, comes down to who is excluded. Globalism has many flaws, but one thing it can be credited for is lifting millions out of poverty, by giving poor countries the opportunity to access wealthier markets.

“Friend-shoring would tend to exclude the poor countries that most need global trade in order to become richer and more democratic,” Raghuram Rajan, the former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund and former governor of India’s central bank, said in a recent commentary published by Project Syndicate.

For mining, it’s 20 years too late

At AOTH we’ve been saying for years that the West isn’t doing enough to secure supplies of critical minerals, so we’re behind the Minerals Security Partnership, an example of friend-shoring, 100%. The problem is it’s too late. For the past two decades, China has been signing offtake agreements to procure the metals it needs to grow and modernize its economy, the second largest in the world behind the United States.

After 20 years of investing in overseas mineral deposits, China now has a lock on many of the world’s metals, or the processing of them. This includes iron ore, copper, lithium, graphite, cobalt, and rare earths.

According to the US Geological Survey, the United States is reliant on totalitarian regimes with dictators installed for life for 32 of 47 minerals — an eye-watering 70%! We are of course talking about China (23) and Russia (9).

For friend-shoring to work with respect to mining, all the friendly countries would have to have enough resources to trade among themselves. Unfortunately, the reality is that most of the metallic resources they want are controlled by regimes hostile to them.

If most of the world’s mine production is already going to China, either through offtake agreements, Chinese state-owned ownership of overseas mines, or mines partly owned by Chinese companies, the question is, how much can friend-shoring help the West to secure supplies of industrial metals needed for infrastructure buildouts, like copper, zinc, lead and aluminum, and the new green economy that demands electrification & decarbonization metals including copper, nickel, lithium, graphite and cobalt?

At the end of the day, friend-shoring will only make existing shortages of metals worse. By only accepting 20% of the most developed countries to trade with, 80% of the world as a source for raw materials, and as a manufacturing base, would be cut off. We are talking about a very small pool of metals supply to draw from.

Conclusion

All in all, friend-shoring is a very bad idea, but it does have one silver lining. The tendency is for governments with lots of natural resources to guard them closely. Resource nationalism will limit the amount of new metal likely to come to market and climate change is already having an impact on mining, for example there is less water available for mineral processing in Chile. Friend-shoring is just one of many factors that will drive commodity prices higher, in the long-term.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments