Who are behind the gold and silver buying — part II

In our previous article outlining the key players in the precious metals market, we highlighted global central banks as being one of the main driving forces behind gold’s rising demand.

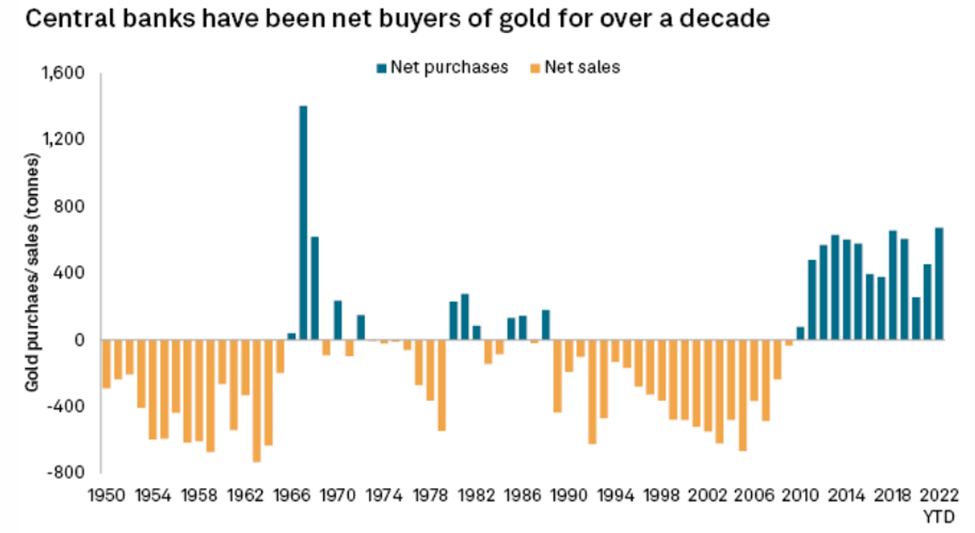

The lender of last resort for their respective countries, central banks have been stacking up on gold to meet their financial obligations since the 2007-08 financial crisis. Bloomberg previously reported that banks have been buying the most gold since the United States abandoned the gold standard in 1971.

As of today, central banks are enjoying their longest period of gold buying, which represents a dramatic shift in attitude from the 1990s and early 2000s.

Strong central bank buying

Latest data from the World Gold Council further solidifies the trend of relentless gold buying by central banks observed in recent times. During the first quarter of the year, the banks collectively added 228 tonnes to global reserves, representing the highest rate of purchases seen in a first quarter since WGC began recording the data in 2000.

This follows up on what was already an impressive year of buying 2022, during which central banks’ added 1,136 tonnes valued at some $70 billion, their most amount of purchases in 11 years. Most of these were made during the second half, which saw 862 tonnes purchased.

The continued buying, as mentioned before, underlines a monumental shift in official attitudes towards gold for nearly two decades starting from the 90s, when central banks, particularly those in Western Europe that own a lot of bullion, were selling hundreds of tonnes a year.

After the financial crisis, European banks stopped selling, and a growing number of emerging economies have become major buyers.

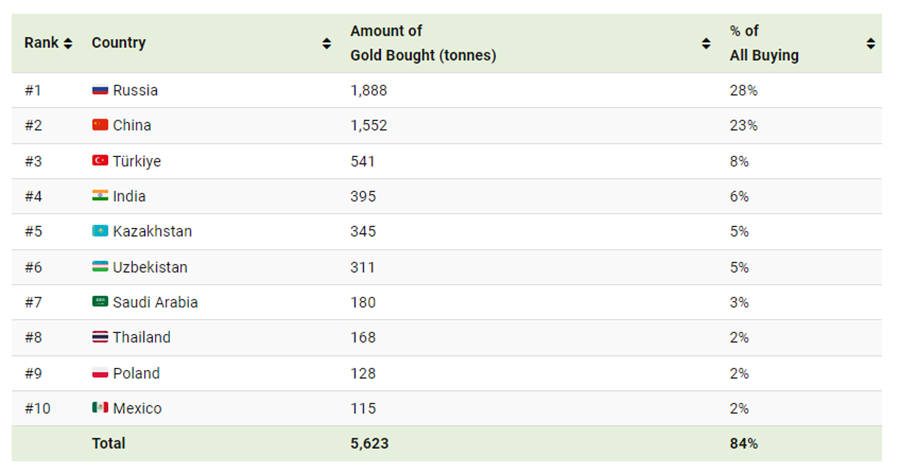

Amongst the most aggressive buyers are Russia and China, which make up about half of the total tonnage bought worldwide over the past 20 years. Behind them was Turkey, which ramped up purchases to a world-leading 148 tonnes last year.

Commenting on this recent trend, the WGC said it expects net central bank gold buying to remain robust through 2023 given the better-than-expected Q1 data, as emerging market banks will remain relatively under-allocated to gold.

More than just diversification

At AOTH, we think there are multiple layers to the recent patterns in central bank buying that go beyond bullion’s functions as a reserve asset.

Central banks traditionally like gold because the metal is expected to hold its value through turbulent times and, unlike currencies and bonds, it does not rely on any issuer or government. It also enables central banks to diversify away from assets like US Treasuries and the dollar.

Louise Street, senior market analyst, said in a CNBC interview that: “Top of the tree for gold in terms of why official sector institutions hold it is always things like its role as a diversification asset, its long term store of value, but increasingly over the last two years, we’ve seen how the importance that they placed on its performance during times of crisis.

So in the aftermath of what’s considered the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, followed by a global health crisis, it would make sense to stockpile bullion for its safe-haven qualities; yet this may not tell the whole story.

After all, as WGC’s data showed, central banks have been stashing gold for well over a decade, even during periods when the global economy seemed healthy leading up to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

“It predates COVID. It predates sanctions,” said Joe Cavatoni, chief market strategist for North America with the WGC, in reference to the next wave of crises that sparked safe-haven demand.

‘Strategic asset’

As mentioned earlier, leading this new wave of gold purchases are the so-called “emerging market/developing economies”, which were some of the biggest buyers for over two decades.

These EMDE banks operate a bit differently from Western banks as their economies are under greater risk during geopolitical struggles, and they also tend not to trust the USD reserves.

It’s worth noting that gold-buying statistics like the one shown above only reflect what’s being reported by central banks; analysts believe there is more gold, likely much more, being purchased by the likes of Russia and China than what’s made public.

The rationale behind these purchases, according to industry experts, is to protect against foreign seizures, as many of these banks want to hold more bullion as a buffer against any current or future sanctions. The Central Bank of Russia, for example, can use gold to replace the USD (i.e. “de-dollarization”) and circumvent Western sanctions when it comes to international trade.

“We think this trend of central bank buying is likely to continue amid heightened geopolitical risks and elevated inflation,” UBS said via a Business Insider report. “In fact, the US decision to freeze Russian foreign exchange reserves in the aftermath of the war in Ukraine may have led to a long-term impact on the behavior of central banks.”

In short, there’s an added layer to the motives behind most of the gold buying by today’s central banks.

Forbes Finance Council’s Sanford Mann describes the distinction perfectly: “Where US, European and Asian banks tend to see gold as a historical legacy asset, EMDE banks tend to see it as a strategic asset.”

“As globalization accelerates, the non-G-10 nations are expected to ‘re-commoditize’ and ramp up gold holdings,” Nicky Shiels, head of metals strategy at MKS PAMP, mentioned to Forbes.

We also can’t forget that gold is one of the best hedges against inflation. Consider this: in the 110 years since the US Federal Reserve was created, the USD has lost 99% of its purchasing power, while gold has barely been touched by relentless annual inflation. Inflation is also a main reason why countries like Turkey, which saw an over 80% rise in price levels, bought more gold last year.

But what if all of these motives don’t fully explain the recent CB purchases? After all, central banks are experiencing by far the longest period of net purchases on record since 1950.

Most prerequisites for past gold purchases (risk of financial turmoil, inflation etc.) are still prevalent, yet the buying patterns over recent years display something stronger — another motive, per se — that propels banks to buy more gold.

Potential gold revaluation

A deeper analysis left us with an interesting idea: All this gold buying may have to do with the massive losses central banks have accrued over the years – gold can be used to help them get out of debt.

The idea is quite simple; It revolves around using the increased value of the banks’ gold holdings (i.e. what investors call “unrealized gains”) to write off sovereign bonds. This practice would be especially applicable to the European central banks, as they accumulated most of their bullion during the Bretton Woods era when gold was valued at a measly $35 an ounce.

Now that the metal is trading at about $2,000/oz, central banks are now sitting on unrealized gains worth hundreds of billions of dollars (Germany, for example, bought its gold for €8 billion euros; today they’re worth around €180 billion euros). Of the many ways in which these humongous gains can be “weaponized” to their advantage, banks can simply use them to cover debt.

We also need to remember that the government-debt-to-GDP ratios in many European countries are at all-time records, so this is a critical time for their central banks to make a call on whether to write off sovereign debt and provide relief to their respective governments.

But just how are central banks able to do that? As we explained earlier, all it takes is a simple maneuvering of the balance sheet with the so-called “Gold Revaluation Account” (GRA), which can be used to record the increased nominal value of the gold reserves and offset the losses from other asset classes (i.e. currency, bonds).

In a way, a GRA functions like equity, and it can inflate a bank’s balance sheet because it effectively has no limit, as its value is synced with that of gold (i.e. when gold price goes up, the GRA goes up). Though should gold prices plummet, it could also sink the balance sheet, as the GRA would turn negative and eat into a bank’s net worth.

For this exact reason, GRAs are currently prohibited within the EU, but when push comes to shove, rules can always be bent especially during a mounting debt crisis.

Interestingly, GRAs have been used once before. In the 1930s, gold was “revalued” by central banks after countries went off the gold standard and devalued against gold. Eventually, the banks re-pegged their currencies to gold at a higher price, leaving GRAs to be used as they saw fit.

Another gold standard?

Of course, everything is just speculation at this point, but it’s still interesting to see that none of the European banks have publicly ruled out another gold revaluation.

At least those asked by Jan Nieuwenhuijs, a gold analyst at Gainesville Coins who has been driving this narrative and staying on top of this for about two years, didn’t deny such a possibility.

In his blog, Nieuwenhuijs noted that countries like Germany and France have been repatriating their gold and bolstering their reserves up to wholesale industry standards, as if there was an unwritten rule within the Euro nations.

The drastic change in Europeans’ stance on gold from the 90s, according to Nieuwenhuijs, seems to be part of a much “bigger project” in preparation for a new version of the gold standard in Europe.

To do that, as he speculates, gold must be spread evenly across the Eurozone countries so that everyone can benefit to the same degree. Nieuwenhuijs believes there is already a mechanism in place to “harmonize” their gold reserves, drawing evidence from statements shown on various banks’ official websites.

A deeper dive into data showing how much gold these nations are holding relative to their reserves, as well as the ratio of total reserves to GDP, backs up Nieuwenhuijs’ hypothesis, which is: Gold reserves evenly spread across nations, proportionally to their GDP, allows a smooth transition towards a global gold standard.

In short, there can be a multitude of reasons explaining why central banks across the world are buying gold. Macroeconomic and geopolitical risks are just one part of the equation, but the more fascinating angle would be the massive debt and financial losses accumulated by these banks.

Higher investment in gold

Rising alongside central bank purchases is gold’s investment demand, which picked up steam following the recent banking crisis in the United States.

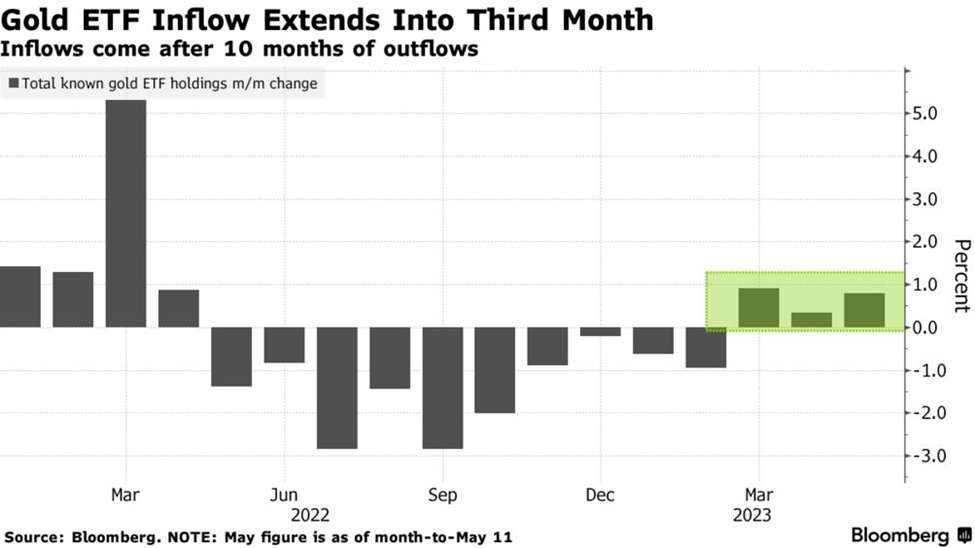

In the same CNBC interview, WGC’s Street noted that there was a noticeable spike in gold demand in March after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the first of what has become a series of failures in the US banking system among regional institutions exposed by higher interest rates.

As a result, the month of March saw significant gold-backed ETF inflows driven by the fears of systemic risk in the economy, which partially offset outflows over the first two months of the year. These risks also extended the inflows into April, with North American funds leading the way by adding $1 billion worth of holdings.

Analysts at ANZ Banking Group predict that flows into gold-backed exchange-traded funds are likely to stay positive for the rest of this year given the many tailwinds for gold, in particular as the Federal Reserve nears the end of its rate-hike cycle.

As the WGC had previously pointed out, ETFs and similar products now account for a significant part of the gold market, with institutional and individual investors using them to implement many of their investment strategies.

Speaking of investment strategies, the latest quarter saw a noticeable recovery in the OTC market that is consistent with investor positioning in the futures market, taking overall gold demand 1% higher year-on-year globally.

Gold bar and coin investment remained strong as well, exceeding 300 tonnes for the third consecutive quarter – the first time this has happened since 2013, WGC data showed.

Overall, global investment demand totalled 274 tonnes in Q1 2023, up 9% on the previous quarter.

Conclusion

Increased demand from both central banks and investors provides further confirmation that precious metals, in particular gold, are the commodities to look at in 2023. It’s not a coincidence that gold prices have been flirting with record highs over the past weeks; silver, too, has been pegged to hit multi-year highs.

Experts remain bullish on gold (and silver) for the rest of the year, with a pivot in the Federal Reserve’s rate hike path acting as the next trigger. Most investors now anticipate the US central banking cutting rates sooner than previously anticipated, with over a 70% chance of that happening in July.

As we’ve previously established, gold’s value tends to be negatively correlated with real interest rates, as well as the US dollar, which many suspect is losing its dominance on the global stage. The banking crisis pretty much affirmed the USD’s vulnerabilities.

CMC Markets recently said a Fed pivot will trigger a sell-off in the US dollar and tank bond yields, sending gold prices up to between $2,500 and $2,600 per troy ounce.

“The story is all about gold,” Will Rhind, founder and CEO of GraniteShares, recently said on ETF Edge, a CNBC segment covering various topics on modern investing. ”[It’s] the only major metal to remain firmly in the green for this year.”

“Gold is really serving its purpose at the moment as a way for people to park money in a non-correlated asset as they worry about what might happen,” Rhind added, referring to the ongoing banking crisis as well as the potential fallout from rising debt.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments