War derails plan to ditch coal after UK championed global cuts

When the COP26 climate talks concluded in November, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson declared the world had reached a point of no return in phasing out coal. At the same time, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba warned Europe that Russia was amassing forces near its border.

Those seemingly unrelated proclamations in Glasgow and Kyiv have become entwined seven months later as Russia’s war on Ukraine forces countries to make up for limited gas supplies. The UK now aims to keep a reserve of coal-fired plants available this winter rather than shutting almost all of them over the next three months as planned.

Efforts to get rid of dirty power are being slowed as the war hits European economies, with soaring gas and electricity prices stoking inflation and raising the spectre of recession. While peers such as Germany are also rethinking coal ahead of this winter, the change of tack by the UK in particular highlights how energy security has turned into the top political priority in such a short time for a government that was so zealous at COP26.

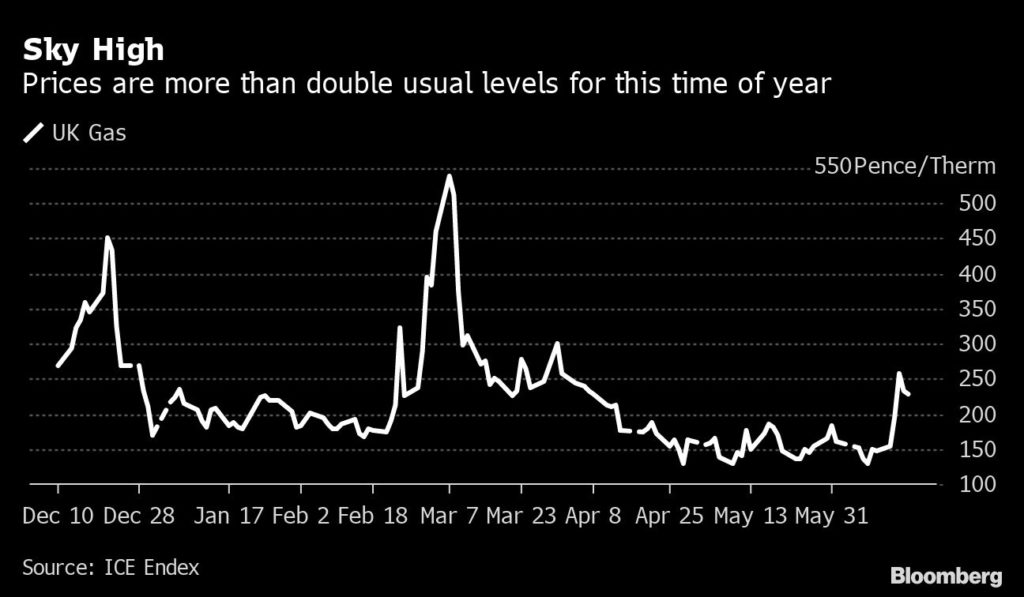

UK gas prices were up almost 50% last week alone. While the country only imports 4% of its gas from Russia, the market is exposed to prices in Europe where cuts to flows along a key pipeline are driving huge spikes in costs. Even environmentalists concede that higher emissions in the short term may be the cost of reducing reliance on Russian fuels in the longer term.

“We have bigger problems to worry about,” said Dave Jones, a global electricity analyst at London-based climate think tank Ember. “The government is taking some decisions — like keeping a coal power plant open — that, to some people, look like a softening on fossil fuels. To me, it looks like a rational short-term decision to help keep the lights on.”

The commitment remains to end coal generation by 2024 and boost renewable sources such as wind and nuclear energy. Coal emits almost twice as much carbon as burning natural gas. The issue now, though, is timing. Operations are being extended at least at one station that would otherwise have closed. Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng has described the measure as a “sensible, precautionary step.”

Last week, Electricite de France SA signed a deal to keep a unit of its West Burton A coal plant on standby in case it’s needed this winter. That comes after the government asked National Grid Plc in May to secure extra backup supply from plants that were about to close or weren’t operating. Deals with Drax Plc and Uniper SE are expected to be announced soon, too.

“With uncertainty in Europe following the invasion, it’s right we explore all options to bolster supply,” Kwarteng said on Twitter on June 14. “If we have available backup power, let’s keep it online just in case. I’m not taking chances.”

In Germany, a similar reserve is being extended to include retired stations in case Russia cuts off supplies to Europe completely. The stations could be used for six months as a lever in a three-stage emergency plan. Unlike the UK, Germany is abandoning nuclear after a promise made in the wake of the Fukushima disaster in 2011 and shut down the remainder of its nuclear capacity this year.

Playing it safe, though, won’t come cheap for the UK. EDF, France’s biggest power supplier, will receive tens of millions of pounds for keeping the plant available, a person familiar with the matter said. That extra cost will be recouped from households at a time when people are already struggling with record-high bills and interest rates are rising.

Johnson’s Conservative government has been excoriated by opponents for not doing enough to help the nation through the worst cost-of-living crisis for decades. It refused to impose a windfall tax on energy company profits like in other European countries, though backtracked as inflation accelerated. Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak also promised a one-time payment for all households to help reduce energy bills in the fall when a price cap set by the regulator is expected to jump again.

“Once again this government finds itself flailing around for answers to the energy crisis, and costing us all more in the process,” said Alan Whitehead, the energy spokesman for the opposition Labour Party, which overtook the Conservatives in opinion polls late last year. “In its efforts to keep the lights on this winter — the most basic requirement of our energy system — it’s now having to rely on more coal, the most-polluting form of energy.”

Leaders around Europe agree that building more renewable capacity is the best way to wean the continent off Russian gas and ultimately cut emissions. If ministers allowed the lights to go out this winter, though, that could harm the push to net zero in the long run, said Josh Buckland, partner at energy consultant Flint Global and a former government adviser.

The UK government’s stance toward phasing out oil and gas supplies has indeed softened in recent months. When the COP26 summit ended, Johnson said the final communique agreed by leaders “united the world in calling time on coal.” The pact, signed by nearly 200 countries, pledged to phase down the use of unabated coal power.

“We will hold all coal producers, importers and mining countries around the world to their commitments to reduce our global dependence on coal,” Johnson told the UK Parliament. “They have made them in black and white in the Glasgow climate pact and we will hold them to account.”

Spin forward, and the Jackdaw natural gas field in the North Sea was approved earlier in June, eight months after the country’s regulator blocked the project on environmental concerns. Companies will also be able to offset some of the new 25% windfall tax on oil and gas profits by making fresh investments in oil and gas extraction.

The UK has gone from spearheading the end of coal to a “farcical” extension of coal-fired power stations, said Luke Murphy, associate director for energy, climate, housing, and infrastructure at think tank IPPR.

Part of the problem is that the UK government didn’t focus on energy security in recent years, leading to under-investment in the industry, said John Browne, the former chief executive officer of oil giant BP Plc. “It’s a bit like defense: a nation can’t work without energy,” he said.

In particular, the rapid decline in North Sea oil and gas production has left the UK without enough homegrown power sources and more vulnerable to any kind of external shock. That will keep dirty fossil fuels such as coal in the mix, said Browne, regardless of the “aggressive push” by the government. “They will be with us for quite a long time,” he said.

(By Rachel Morison and Jess Shankleman)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

JOHN ENGLAND

The UK has a particularly difficult problem;its few remaining coal fired power stations are all geriatric and operate very inefficiently at subcritical pressure. The high point in Government energy policy was at the beginnining of 2007 when Gordon Brown launched the first carbon capture competition. Every decision taken since then by politicians from all parties have been stupid. In 2010 I was part of the team trying to develop the Hatfield Coal fFired Carbon Capture Project which was comfortably Europe’s leading Carbon Capture Project. It would have been built by now if the Government had supported it as they should have done.