Want to see a real short squeeze? Come to the tin market

(The opinions expressed here are those of Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

Finding financial market shorts to squeeze is this year’s investment rage.

After the Reddit assault on individual stocks, retail investors tried, unsuccessfully, to pull the same trick in the silver market.

Commodity markets are tougher to crack than individual shares, particularly if there’s no underlying shortage. Silver notched up consecutive years of oversupply between 2016 and 2019, according to the World Silver Institute.

Tin has been in three years of global supply deficit, according to the International Tin Association

Tin, by contrast, has been in three years of global supply deficit, according to the International Tin Association (ITA).

So if you want to see what a real commodity squeeze looks like, come to the London Metal Exchange (LME) tin market.

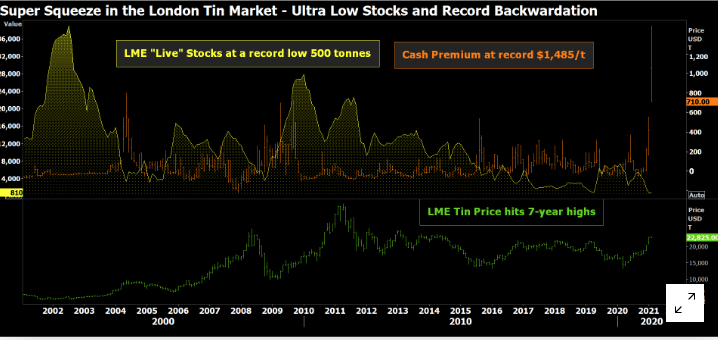

Stocks are nearly depleted, the contract is experiencing unprecedented degrees of technical tightness and the tin price is punching out seven-year highs.

The big short in the tin market is not a hedge fund but rather the physical supply chain, which is struggling to meet resurgent demand.

Tin turns wild

There are currently 810 tonnes of registered LME tin stocks, which is a lot less than the 33,608 tonnes of silver sitting in London vaults at the end of December.

With 310 tonnes awaiting load-out, the physical liquidity base of the LME tin contract has shrunk to a record low of just 500 tonnes. That’s half a day’s worth of global consumption.

Time-spreads have whipped out to surreal levels. The premium for cash metal over three-month delivery closed Tuesday valued at a record $1,485 per tonne.

The London tin market has seen low stocks and bouts of tightness before. It’s even had its own version of the Hunt brothers’ infamous silver squeeze with a prolonged attempted corner of the market in 2009-2010.

But this week’s spread action has been unprecedented. Even after easing to $990 per tonne by Thursday’s close, the cash-to-three-months time-spread hasn’t been as tight this century.

Outright prices, meanwhile, have marched ever higher, with three-month tin hitting a seven-year high of $23,435 per tonne this week and cash metal touching an eight-year high of $25,001.

Physical squeeze

Such a high premium for cash metal should suck physical tin into the LME’s warehouse system.

But it’s unclear how much is available given clear signs of tightness in the physical market, where premiums are soaring, particularly in the United States.

The premium for tin in warehouse in Baltimore rose from $550-650 per tonne to $775-1,000 per tonne over LME cash during January, according to Fastmarkets, the highest level since it started assessing the U.S. tin market in 2016.

Imports have been hit by a lack of containers, part of the broader COVID-19 disruption to shipping, and the LME’s U.S. warehouses hold only a residual 20 tonnes.

European premiums are assessed at a more modest $400-500 per tonne over LME cash but they too are rising as holders become increasingly reluctant to part with units. LME warehouses in Europe hold just 15 tonnes, all at Rotterdam and all awaiting departure.

It’s this physical tightness that has driven the tin price higher in recent weeks, according to the ITA which says “we expect prices to hold with no end to logistics issues currently in sight.” (“Tin in the News,” Jan. 28, 2020).

It also means that LME paper shorts are competing with physical shorts for spare units.

Shanghai exuberance

It’s probably just as well the Robinhood army hasn’t found a way to surge into the LME tin arena, which remains populated by industrial hedgers and a smattering of professional funds.

The London market is doing just fine generating its own tightness without any retail investment help.

However, in China, there seems to have been a mass stampede to join the action.

The Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE) tin contract, launched in 2015, hit life-of-contract highs at the end of January with volumes and open interest exploding.

China’s production was severely disrupted by the pandemic last year, even as its manufacturing sector roared back into life

The equivalent of almost 500,000 tonnes traded over just two days at the turn of the month – more than a year’s worth of global tin production. Market open interest hit a life-of-contract high of 80,686 contracts.

Such activity spikes in China’s commodity markets are a sure sign of retail crowd surges and tin seems to have moved onto the Shanghai street’s investment radar.

Ironically, ShFE stocks of tin at 7,450 tonnes look positively bountiful relative to the depleted LME.

But the proportion of metal on warrant is 93%, very high by ShFE standards, suggesting inventory is going to be sticky.

And, of course, it’s in China, where the broader market seems also to be running short of metal.

The world’s largest producer was a net exporter of refined tin in 2018 and 2019 after doing away with a previous export tax.

But last year saw trade invert as imports ballooned to 17,700 tonnes from 3,000 tonnes in 2019. Net imports of 13,200 tonnes were the highest yearly total since 2012.

China’s production was severely disrupted by the pandemic last year, even as its manufacturing sector roared back into life.

Time trial

The ITA has said it expects global tin output to normalise this year, both in China and in the rest of the world. But it warned that supply would struggle if demand staged the same sort of sharp recovery seen ten years ago after the Global Financial Crisis

All the evidence points to just such a demand rebound and a supply chain that is now working hard to find units in the right place at the right time.

And time is of the essence for anyone short of LME tin because the worst sort of market squeeze is the one when no-one seems to have anything to spare.

(Editing by Kirsten Donovan)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments