Want to dismantle coal power faster? Green the grid

The air is hot, gritty and tastes metallic inside Australia’s largest coal-fired electricity plant, the aging Eraring Power Station that’s into its fourth decade of operations.

At the site’s cavernous turbine hall as much as 6 million tons of coal a year is crushed and loaded into furnaces which reach temperatures of 1,480 degrees Celsius (2,696 Fahrenheit) — about enough to melt steel — to heat 24-story high water-filled boilers. The process creates enough steam to spin giant turbines that generate almost 2.9 gigawatts of electricity annually, a quarter of power demand in Australia’s most populous state.

For now, there’s the same thunderous roar from the process that’s continued since Eraring became fully operational in 1984. But, as soon as August 2025, the plant north of Sydney is scheduled to fall silent.

The asset’s owner, utility Origin Energy Ltd., in February brought forward the site’s planned retirement by seven years. Chief Executive Officer Frank Calabria cited the crumbling viability of coal-fired electricity as a reason, as the fuel faces competition from lower cost energy sources such as solar, wind and batteries.

To shutter Eraring, it’s “not quite as simple as just turning a switch off,” said Tony Phillips, Eraring’s group manager of coal asset operations. First, the burners will be extinguished and then the boilers brought to a halt, taking three to four days to cool down. After that, there’s an arduous process of dismantling, repurposing and rehabilitating the land where the coal plant sits.

With a sprawling area that includes neat rows of electricity transmission lines, Eraring has vast potential to become a location for green energy instead. Origin plans to begin installation of a 700-megawatt storage battery before the coal plant shuts down, and complete the project by 2026 to integrate it with renewables developments across New South Wales. The site itself could host further new infrastructure over time, the company said.

The switch won’t be cheap. Origin estimates restoration and rehabilitation will cost A$240 million ($170 million), and it’ll spend A$5 million over 10 years on community support. Major efforts are underway to find workers new jobs, or to retrain staff, according to Phillips.

There’d been concern from Australia’s previous government that dismantling Eraring years ahead of schedule could make the country’s main electricity grid less reliable, and raise power prices. But those fears are probably misplaced, according to the Australian Energy Market Operator, which manages national electricity and gas systems. Plans to add new transmission and renewables in New South Wales, including proposals for 1.7 gigawatts of large-scale wind and solar, mean the region’s electricity network is likely to “meet or exceed the reliability standard,” even without the coal plant, according to Merryn York, AEMO’s executive general manager of system design.

Australia’s been able to accelerate its move away from coal because renewables are growing so quickly, thanks to abundant sunshine and wind and relatively low costs of installations. The country is a world leader in residential solar, with almost a third of homes fitted with panels.

That influx of clean power assets has sent wholesale electricity prices tumbling and seen daytime power demand — when rooftops are bathed in sunshine — hit record lows, eroding profits for more expensive coal-based power generation.

“The amount of daytime demand is becoming so small that coal plants are left in a battle amongst each other to remain online,” said Johanna Bowyer, a lead research analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Aging coal plants are also struggling with reliability, with outages this month removing about a third of the fleet’s capacity to produce power.

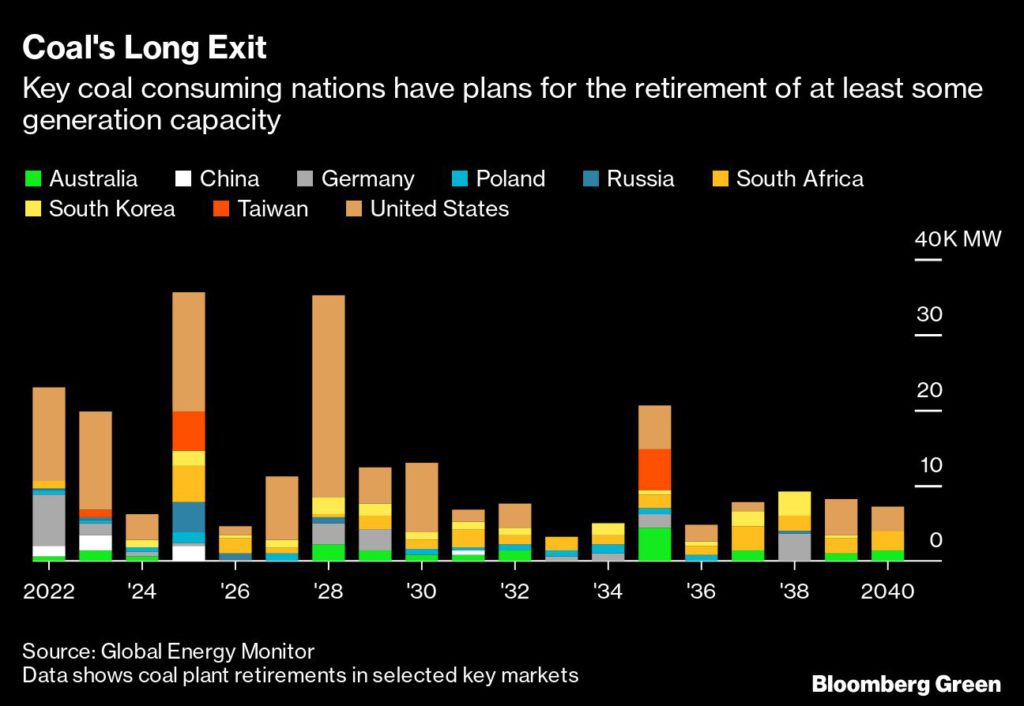

That makes Australia a global test case for the transition of power grids that remain dominated by coal, including in the US, South Africa and some European nations aiming to end reliance on Russia’s fuel exports. South Australia in particular, where renewables accounted for 100% of demand on 180 days last year, is being looked to for lessons on how best to remodel post-coal energy systems.

Australians added a record 3.2 gigawatts of household solar last year. That’s “more than the output of Eraring and it’s cheaper than what we can produce energy for,” said Phillips. “Really, that makes coal-fired power stations into the future uneconomical.”

Hong Kong-based CLP Holdings Ltd.’s EnergyAustralia unit has made a similar conclusion, and aims to close its Yallourn power station in 2028, four years ahead of previous plans. It’ll also close down its Mt Piper plant early, in 2040. AGL Energy Ltd., the utility responsible for the largest share of Australia’s direct greenhouse gas emissions, rebuffed a takeover approach led by Brookfield Asset Management Inc. aimed at speeding its path to net zero. Technology billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes has become its largest shareholder and is pressing to shutter coal plants and add more renewables.

AGL estimates there’s a A$1.4 billion cost to replace its Liddell coal plant in the Hunter Valley mining region of New South Wales, which will close by next April. It’ll add new assets in the area including a 500-megawatt battery, renewables, gas peaker plants, pumped-hydro storage and a synchronous condenser.

A fresh Australian government, along with an expanded slate of climate-focused independent and Greens legislators, should add further support to the nation’s energy transition. Scott Morrison, ousted as prime minister last week, had previously backed the country’s coal fleet to continue “as long as you possibly can,” and rejected global pacts on phasing out the use of the fuel.

Australia’s electricity sector accounts for almost a third of the nation’s direct emissions, and more than 85% of that total comes from the country’s coal-fired plants. Origin’s Eraring alone emits 12.7 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent a year.

That one of the world’s largest coal exporters and the source of some of the highest per-capita emissions from the fuel is abandoning it faster than expected is testament that the transition is possible, said Richie Merzian, director of the climate and energy program at the Australia Institute think tank, which presses for more additional emissions reduction.

“To see Australia plan for the future past coal is a demonstration of transition from one of the last holdouts,” he said.

(By Georgina McKay and David Stringer)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Steve O'Dea

Interesting article… could use the correct units for power though as this would materially change the conclusions of the article.

Power can be considered as a moving object where the speed is watts and the distance covered is watt-hours; describing a power station as “generating 2.9 gigawatts of electricity annually” is like saying a car “travelled 100km/h annually”… it doesn’t make sense.

Eraring, which has a generating capacity of 2.9 GW, has historically generated ~16,000 GWh annually (~62% utilisation).

The 3.2 GW of household solar installed last year is great, but unfortunately it doesn’t replace a 2.9 GW capacity coal station due to significantly lower utilisation. Household solar in Australia has a utilisation of around 23%.