Carbon offsets: New $100 billion market faces disputes over trading rules

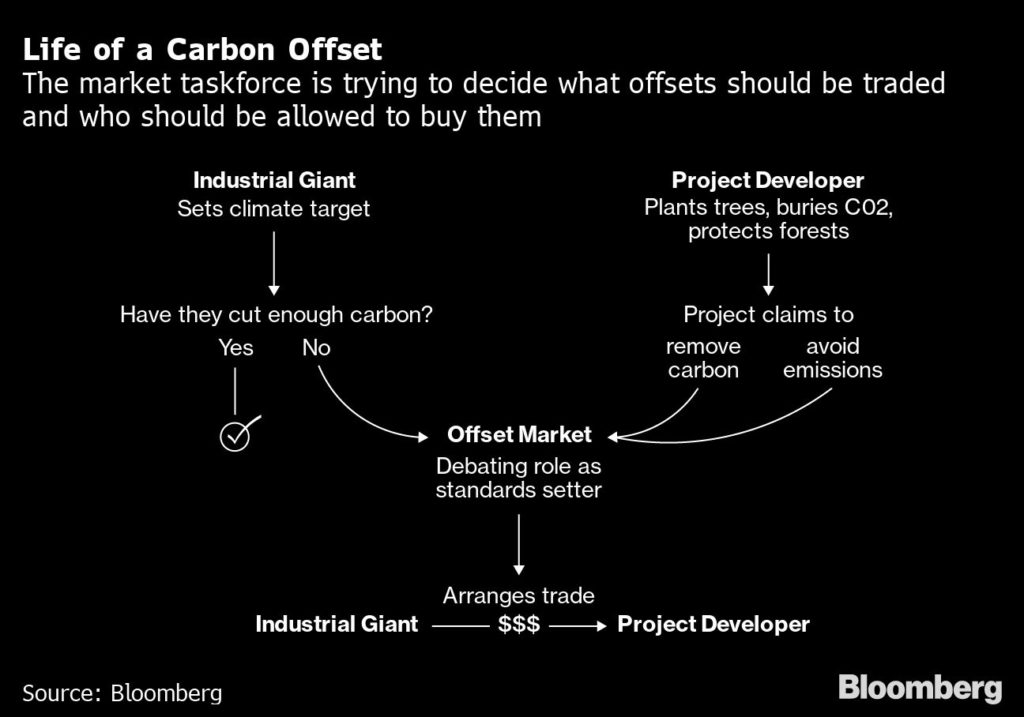

Global warming is the world’s biggest market failure, so the solution might just be better trading. On one side of the trade would be the companies clogging the atmosphere with heat-trapping gases; on the other countless projects to eliminate the problem by planting trees or building machines that capture carbon dioxide. Create a market that turns a ton of removed carbon into a commodity just like corn or copper, and money will flow from the emitters to the fixers.

That’s the theory behind the new carbon-offset market being conceived by Mark Carney, a former governor of the Bank of England, and Bill Winters, the chief executive of Standard Chartered Plc. The two financial veterans late last year set up a rule-making taskforce populated by hundreds of bankers, airline executives, sustainability experts, commodities traders, scientists and other business leaders.

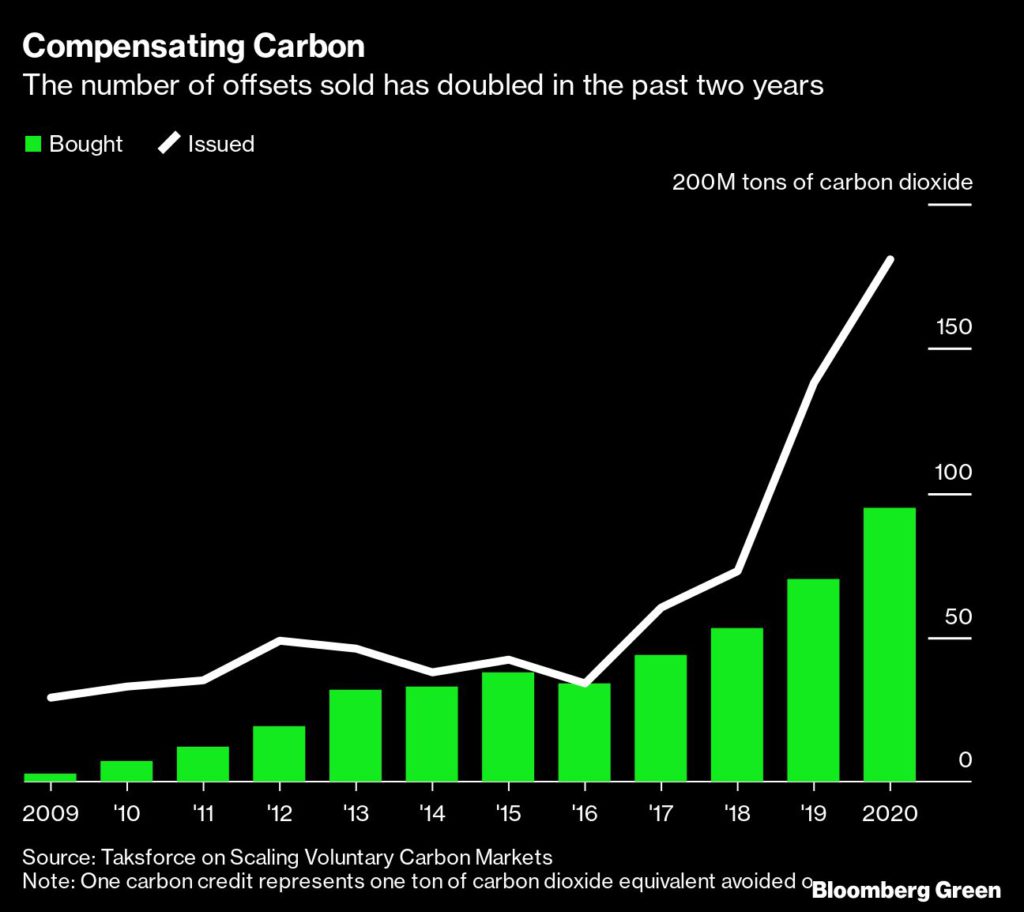

Carney says the unified market for carbon offsets could be worth $100 billion by the end of the decade, up from about $300 million in 2018. He and Winters plan to use the findings of the private-sector Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets to help launch a pilot program before November, when the next round of global climate talks will be held in Scotland.

But the taskforce’s closed-door deliberations have dragged on for months. With time running low, there’s sharp debate on fundamental questions.

Interviews with more than a dozen people involved in this new initiative as well as internal emails seen by Bloomberg Green reveal impasses over make-or-break issues such as which companies can use offsets to reach their climate goals and whether credits based on avoiding emissions—the vast majority of offsets currently available—should be part of net-zero plans. (Bloomberg Philanthropies has pledged funding for the initiative.)

“The more time passes, the more pressure there is,” said Eli Mitchell-Larson, an Oxford University environmental scientist helping to develop the rules for this new market. He said some leading members are rushing to start trading without first agreeing on how offsets fit into the climate fight. “People want to buy a product.”

Getting the contours of the market right could create a powerful, standardized weapon in the fight against rising temperatures—a tool that can be embraced by scores of companies that have pledged to reach net-zero emissions. A key objective is to come up with a “core carbon principle” label that could be used to mark offsets that meet its standards, akin to how groceries might be labeled organic. Members have spent months arguing over the criteria for inclusion, with sharp divides over how high to set the bar.

If Carney’s forecast for market demand proves correct, hundreds of companies will soon begin a buying spree for carbon offsets. Just the 18 oil majors that already have net-zero goals will eventually need to erase 3.3 billion metric tons of annual emissions, according to clean-energy researchers at BloombergNEF. That’s nearly 18 times the amount of carbon offsets issued in 2020.

But getting the new market rules wrong could be even more powerful—and deeply damaging. To succeed as a clearinghouse for greenhouse-gas removals, what’s sold on the market has to be beyond doubt. “If they generate a lower carbon benefit than they claim and the company is still emitting, well then you end up with more emissions than you would have otherwise,” said Mitchell-Larson. “We have to be open to the idea that the voluntary market might fail.”

That makes ongoing debates about what can and can’t be traded crucially important, especially if respected corporate participants or climate organizations end up declining to support the taskforce’s nonbinding recommendations. In one email exchange between members, Unilever Plc’s representative, Thomas Lingard, suggested the consumer-product giant would consider withdrawing support if there wasn’t more transparency on decisions.

The job for Carney and Winters now is to resolve disagreements among the 400-plus taskforce participants, even as many important players remain at odds. Interviews and statements from the two taskforce organizers, rank-and-file members and experts, some of whom requested anonymity, show the fault lines that remain with just months left to finish the work.

Here’s a look at the four biggest questions hanging over the taskforce.

Who gets to buy offsets?

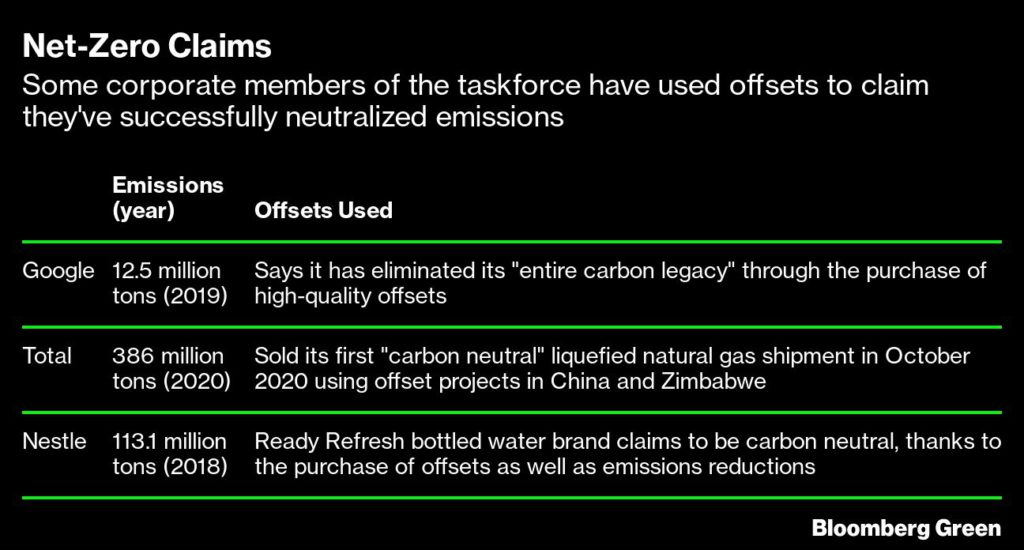

Customers in the U.K. filling up their tanks with Royal Dutch Shell Plc’s gasoline today will see advertisements about the beneficial role of carbon offsets. Pay a small fee at the pump, drivers are told, and their emissions are neutralized by funding a forest program in Peru. There’s more than marketing happening here: Shell is one of a growing group of companies with commitments to zero out emissions by mid-century, and purchasing offsets is a significant part of the solution.

The danger is that cheap offsets can be used to avoid the hard work of actually cutting emissions. The practice is so common that the certificates are often described by critics as “papal indulgences,” reminiscent of the way Catholics in the Middle Ages made payments to the Church to eliminate the stain of sinful deeds.

For weeks, taskforce participants have been mired in a debate over when corporate emitters can tap the offset market to cover their ongoing climate sins. Should companies be allowed to balance their carbon ledgers by purchasing offsets without first exhausting all other options to clean up their business?

“That’s not our job to answer that question,” Winters told Bloomberg Green in an interview on May 19. “The whole subject of corporate claims was one that we always recognized was not part of the core mandate of the taskforce.”

Yet last month organizers of the taskforce appeared to backtrack, proposing a statement that would wade into the debate by suggesting that companies should be able to use offsets to boost their climate credentials. Some taskforce members refused to put their names on the document because it verged on greenwashing. A sizeable faction argued that companies shouldn’t be able to use offsets if they’re not taking direct steps to cut pollution.

Carney has even expressed this view himself: “You can’t buy offsets, as a company, unless you are reducing your absolute emissions, unless you have a high-quality net- zero plan,” he told Bloomberg in April.

The comments from Winters and Carney don’t reflect conflict so much as the complexity of an issue with broad disagreement. Winters as taskforce chair now has more direct involvement in the work; Carney, through a spokesperson, said he’s not a leader or member of the taskforce but an “initiator” who acted as an organizer.

Sonja Gibbs, an official from the International Institute of Finance, which helps oversee the taskforce, acknowledged the difficulty of settling the question of who can access the market. “It is clear that we will not be able to reach 100% consensus,” she wrote in an email to members.

Will climate players endorse the rules?

To be taken seriously, the taskforce has to gain the endorsement of an influential gatekeeper in the world of corporate climate accounting. The Science-Based Targets initiative, or SBTi, is a group of experts that sets widely respected standards on what it takes for a company to reach net zero. SBTi doesn’t approve the use of carbon offsets for short-term climate plans until a company has tried every other available fix, be that installing wind turbines, boosting efficiency or switching to cleaner fuel.

The issue of whether a global offset market should accommodate all corporate buyers is so sensitive that taskforce adviser Cynthia Cummis from World Resources Institute, an SBTi member group, would only address the topic in general terms. “It’s a company’s responsibility to reduce emissions,” she said, cautioning against “cheap offsets” that would supplant emissions cuts. SBTi might one day support the use of offsets but only for “residual emissions” that can’t be easily cut, Cummis said, citing air travel as an example.

A split could grow into a bigger problem. Companies with the most widely lauded net-zero goals, such as Unilever and Microsoft Corp., have in-house teams that assess potential offset projects. It’s a bespoke approach that many smaller companies can’t afford. If these well-regarded companies continue to vet projects without adopting the common standard, one senior member of the taskforce predicted that the market won’t take off.

Who governs a global voluntary market?

Financial markets are overseen by government regulators like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which ensure manipulation and fraud are punished. Carney and Winters are advocating for a voluntary market—and that means no government oversight.

Regulating a carbon-offset market isn’t just about stopping rogue traders. The projects themselves can be a source of fraud and abuse. Researchers at the nonprofit group CarbonPlan recently discovered $400 million worth of offsets had been sold in California without absorbing a single ton of CO₂. The Finland-based nonprofit Compensate found 90% of offsets fail to deliver or come with damaging side effects for local communities.

Verifying that an offset corresponds to a ton of CO₂ removed from the real-world atmosphere is a problem climate experts have been trying to solve for years. The new market would only compound this difficulty by demanding clear answers to thorny questions. Should the market allow trade in forest-protection offsets linked to well-documented failures? For how long should an offset remain valid after the original carbon removal?

The clock is now ticking for Carney and Winters as they prepare to finish the preparatory work and disband the taskforce. The hope is that by the end of June the group will have agreed on a set of recommendations for a smaller and more permanent governance. Winters said it hasn’t been decided who will sit on the governing body.

Climate experts participating on the taskforce have expressed concern that finance veterans don’t necessarily have the skills to deal with all the scientific complexities. “It’s overly simplistic to think we might get better results by requiring the presentation of some kind of return-on-investment analysis,” scientist Derik Broekhoff of the Stockholm Environment Institute wrote in an internal taskforce feedback document. In an interview, he said there’s too much focus on enlarging the market without enough concern for the trade-off between quality and quantity.

Mitchell-Larson, the Oxford scholar, said the taskforce hasn’t sorted out how to screen against poorly managed projects. During discussions he’s participated in, he said members couldn’t agree on whether to allow some projects that claim to prevent deforestation. Large offset brokers such as Carbon Direct and registries such as Gold Standard already bar such credits.

What about all those ‘avoided emissions’?

The multiple roles occupied by Carney point to another hurdle in setting up the carbon-offset market. He currently serves both as British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s top climate adviser and a convening figure behind the taskforce. Plus, Carney is a vice chair at Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management, which manages a half-trillion dollar portfolio with an enormous stake in renewable energy.

Brookfield isn’t directly participating in the taskforce but does own Hartree Partners, a commodities-trading firm that is taking part in the process. While Carney has said there’s no conflict of interest, his heavyweight status as leading figure in climate finance means his statements are closely watched by everyone taking part in these debates.

As an organizer of the COP26 climate talks hosted by the U.K., Carney is obliged to remain neutral ahead of negotiations over offsets used by governments and corporations as laid out in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Alok Sharma, the U.K. minister in charge of COP26, has said neither Carney nor the taskforce will inform the government’s position on Article 6. But it’s a fine line to tread.

Carney said in an April interview that the private sector will adhere to decisions about offsets made at COP26. The taskforce said early on that Carney wouldn’t participate in talks that overlapped with Article 6, according to a member who asked not to be named. One result, this person said, is that senior figures behind the taskforce haven’t taken a firm stance on crucial issues such as what counts as a credible offset.

Instead, members have looked at Carney’s public statements for clues. In February, he walked back statements claiming Brookfield had used “avoided emissions” from clean-energy projects to cancel out its entire carbon footprint, including ownership stakes in dozens of fossil-fuel assets.

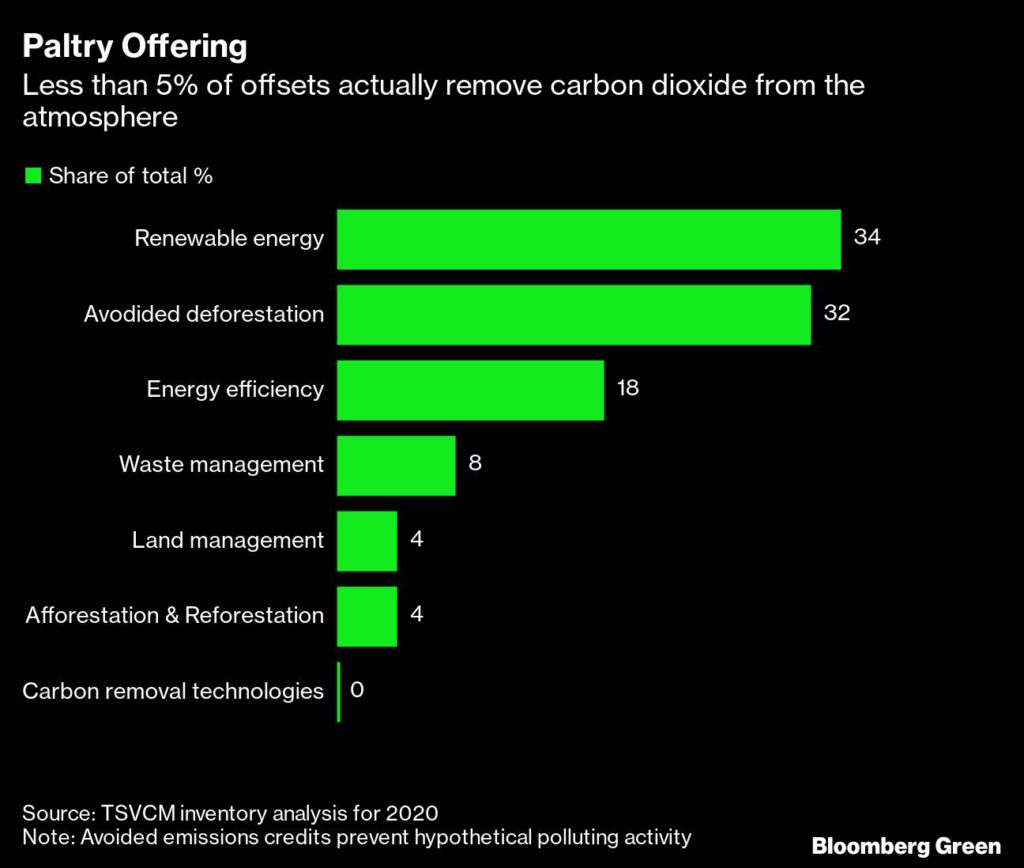

Avoided emissions are widespread—and controversial. Most projects designed to generate carbon offsets seek to prevent trees from being cut down. In other cases a company can claim credit for switching from fossil fuel to cleaner energy. Offsets from avoided emissions made up 96% of all contracts issued last year, according to data compiled by the taskforce.

But to effectively tackle climate change, the majority of offsets sold will have to actually remove CO₂, by planting forests or using technology that can suck carbon out of the air. Groups like SBTi and most climate scientists do not accept avoided emissions. Some companies inside the taskforce are still arguing in favor of avoided-emission credits.

Lowering standards is a concern for member Owen Hewlett, chief technology officer of offset broker Gold Standard, which is backed by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature. Hewlett is also on an advisory group for SBTi. “Pressing others to give recognition to companies for using those credits—it’s like having part of an answer and then demanding a question is made to fit it,” he said. “You can’t offset your way to net zero.

(By Jess Shankleman and Akshat Rathi)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Philip

There is NO global warming… its now called climate change because the global warming theory was baloney… as for carbon credits, trading carbon credits, raising the cost of carbon per ton AS A TAX… just shows it is another way for government to take more and more of your money because they need to pay themselves more, conduct massive corruption around the world and keep you from creating wealth and becoming more free of them. Screw carbon credits – carbon taxes.