Volatility storm adds to pain for Chile’s battered markets

The last few months of white-knuckle trading in Chilean assets, on a par with the most unstable of its emerging-market peers, is erasing the final traces of the country’s reputation as the most stable of Latin America.

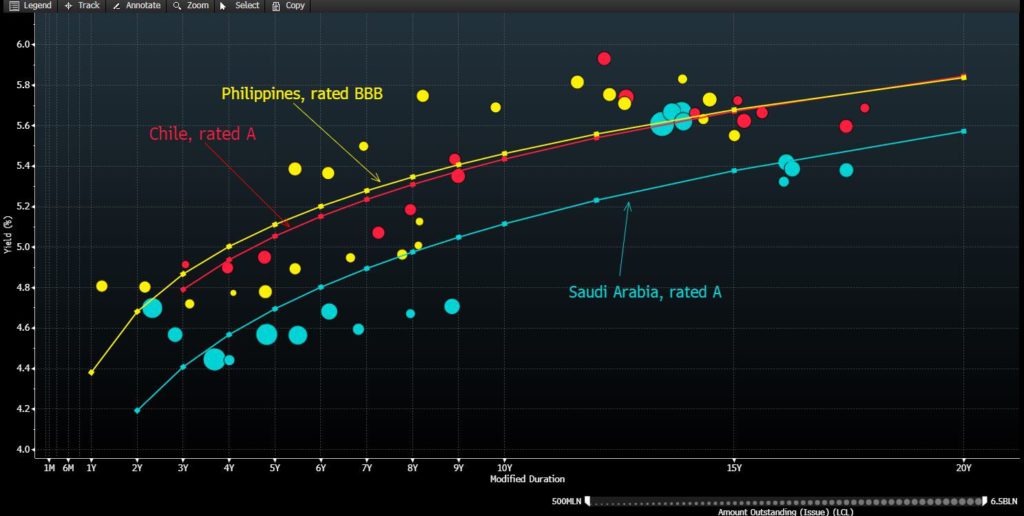

Peso volatility is the highest in the world after the Russian ruble, while local swap rates have swung at an almost unprecedented pace. That unpredictability has pushed many investors to the sidelines, with the nation’s sovereign dollar debt now trading at levels similar to the Philippines, rated two notches below Chile.

Chile’s fall from grace has been a long-time coming. It started even before the explosion of social rage three years ago that brought much of the country to a standstill and shell shocked investors lulled into a sense of security by three decades of steady growth and low inflation. Now, there seems no remedy to the decline. Even the rejection in a referendum of a new constitution that many had warned would undermine investment and growth only heralded fresh declines last month.

“Chile used to be a byword for stability and security, but now that is a distant memory,” said Mario Castro, a fixed income strategist at Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA in New York. “There has been a structural change in Chile, which involves an institutional deterioration and a shift toward a welfare state that will push up fiscal pressure.”

The volatility has reached new highs recently as emerging-market currencies were hit by the strong dollar at a time when Chile is struggling to finance one of the highest current account deficits in the world. That pushed the peso to record lows in July and prompted the biggest intervention program in the central bank’s history.

A-rated

It all used to be so different.

Back in 2017, Chile was rated AA- at S&P Global Inc., on a par with market favorites such as Taiwan and the Czech Republic. Then a mounting fiscal deficit led to a downgrade to A+ that year, followed by another cut to A in 2020.

Now, even that rating seems to flatter Chile, with its dollar debt trading at yields similar to those of countries with a BBB rating such as the Philippines, and far above similarly rated Saudi Arabia, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“There are downgrade pressures” on Chile’s rating, said Valerie Ho, a portfolio manager at Doubleline Group LP in Los Angeles. “The vulnerabilities of Chile are a weaker growth outlook, the uncertainty over future policy in the mining sector and spending plans.”

Chile’s Finance Ministry didn’t respond a request for comment.

Going wrong

What really shook Chile and markets out of their 30-year slumber was the riots of October 2019 that brought the army back on the streets and saw the then president almost besieged in the Moneda palace. Nothing has been the same since.

The market-friendly policies that have characterized the country since the 1980s were called into question, along with the parties that have dominated politics since the end of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in 1990.

Now President Gabriel Boric heads Chile’s most left-wing government in half a century, pushing for constitutional change, while looking to hike taxes on the mining industry, improve labor rights and redesign a pension system based on personal savings. All that within the framework of stalling growth, the fastest inflation in three decades and a soaring current account deficit.

Still hope

Still, a downgrade isn’t inevitable.

Chile’s current account gap will narrow sharply next year as the economy contracts, while inflation slows. At the same time, many expect the price of copper, which accounts for about half of exports, to improve, while output of the metal should rise.

What’s more, Chile is already one of the few countries in the world expected to post a near balanced budget this year.

“Chile will improve in time and will look closer to what it was before,” said Andres Abadia, an economist at Pantheon Economics. “However, returning to being a safe haven in Latin America will depend on how the rules of the game remain in the new Constitution.”

But for now, investors are struggling to make sense of all the changes. The yield on the 5-year peso-Camara interest rate swap, one of the most liquid in the markets, has moved an average 14 basis points per day this year. That compares with an average of about 6 basis points in 2020 and little more than 4 in 2018.

It’s the same with the currency. The peso’s 30-day volatility has risen above that in Brazil’s real and Colombia’s peso.

“For many years inflation was basically nowhere and rates were not moving,” said Carlos Fernandez-Aller, global head of FX and emerging markets macro trading at Bank of America. “A five-basis-point move in Chile was a big deal. Now it’s a completely, completely different story.”

(By Eduardo Thomson, Maria Elena Vizcaino and Valentina Fuentes)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments