Visualizing two decades of Central Bank gold reserve changes

Gold-hoarding nations: Changing gold reserves since 2000

Gold has long been an important hedge in times of uncertainty, and unlike foreign currencies, equities, or debt securities, its value is not dependent on any company or nation’s solvency.

This has made gold an essential part of many national central bank reserves, especially as the monetary supply of many nations continues to expand and central banks are exploring digital currencies which could be reserve or gold backed.

With gold still making up a large part of many nations’ reserves, how have central banks been managing the precious metal?

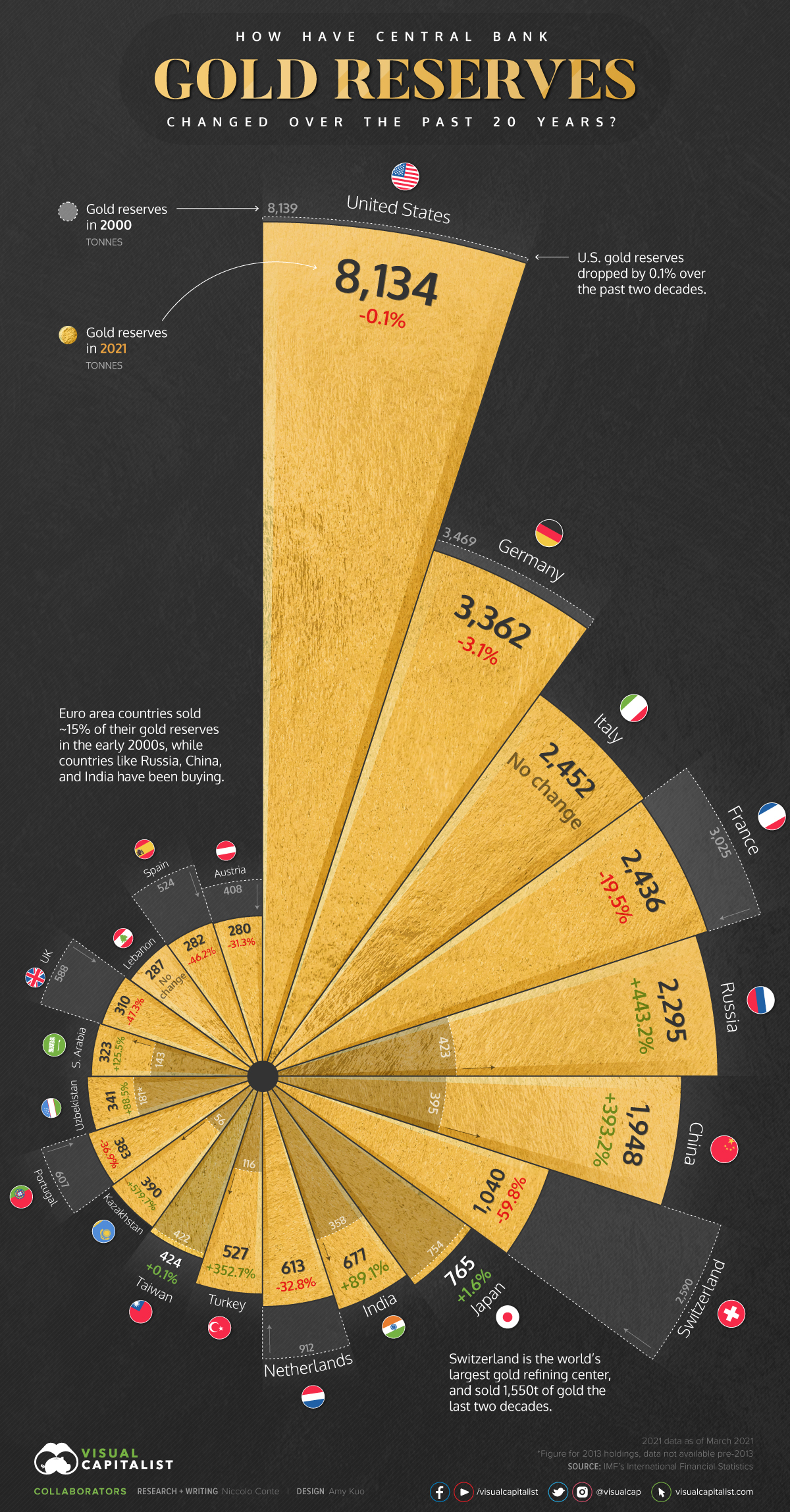

Using data from the IMF’s International Financial Statistics, this infographic looks at the top 20 countries by their central bank’s gold holdings and how their national gold reserves have changed since 2000.

European nations sold gold, but still hold plenty

Many European nations started the millennium by reducing their gold holdings. The Euro Area (including the European Central Bank) sold a total of 1,885.3 tonnes over the past two decades, reducing gold holdings by around 15%.

Despite this, European nations like Germany, Italy, and France still retain some of the largest gold reserves, with Italy not having touched their gold at all over the past 20 years.

After the termination of the Central Bank Gold Agreement in July of 2019, the European Central Bank made it clear that gold is still held in high standard by the Euro Area’s nations:

“The signatories confirm that gold remains an important element of global monetary reserves, as it continues to provide asset diversification benefits and none of them currently has plans to sell significant amounts of gold.”

– ECB

Small countries, big buyers

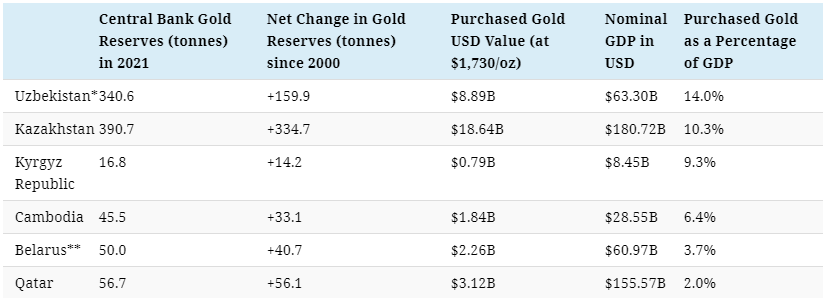

While nations across Europe sold off some of their central bank gold reserves, smaller countries like Kazakhstan, Cambodia, Kyrgyz Republic, Belarus, Qatar, and Uzbekistan have been some of the biggest gold purchasers relative to their GDP.

Large gold purchases of six small nations

*Uzbekistan data only available from 2013 onwards

**Belarus data only available from 2002 onwards

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Database

None of the nations in the table above rank in the top 50 by nominal GDP, however, their central bank reserves have greatly grown in value thanks to their gold accumulation over the past 20 years. Along with this, countries like Uzbekistan are focusing on making gold production and circulation a key part of their economies.

In November of 2020, Uzbekistan introduced a new gold product available at commercial banks to make buying and selling gold more accessible: gold bars weighing 5, 10, 20, and 50 grams in a protective card packaging with a matching QR code for authentication.

As Uzbekistan pushes to become one of the world’s largest gold producers over the next few years, this product reintroduces gold in smaller purchasable amounts for everyday citizens.

A Turkish delight of gold purchases

Since 2017, Turkey has increased gold within their central bank reserves from 116 to 527 tonnes (a 354% increase), while wrestling with rising inflation and a plummeting Turkish lira.

Alongside the central bank’s gold purchases, the Turkish government introduced gold-backed bonds and changes to gold regulations in an attempt to draw out household gold deposits. To further strengthen the nation’s economic independence and cut down gold import costs, Turkey is planning to radically ramp up domestic gold production to 100 tonnes of gold per year.

The country broke records in 2020 with 42 tonnes of gold produced, and the recent discovery of a 3.5M oz gold deposit (valued ~$6B) will help supply the nation’s surging demand for the precious metal.

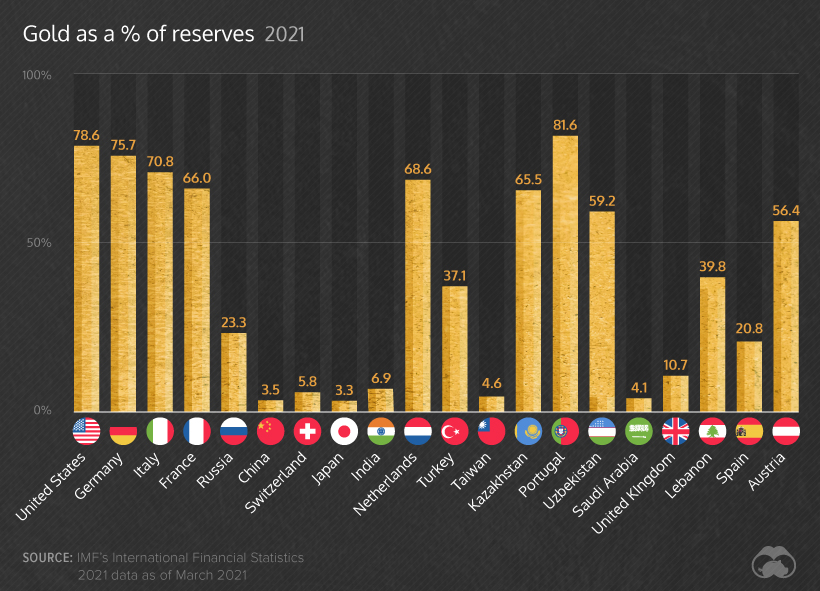

A common trend: Gold is rising as a percentage of reserves

One trend that is common across many nations: gold as a percentage of reserves has risen consistently since Q3 of 2018 as gold’s price has skyrocketed.

Most European central banks have gold reserves above the 50% mark of their reserves despite mostly selling gold over the past two decades. On the other hand, China and India have been aggressively purchasing gold since 2000, and yet gold still remains at single-digit percentages of their total reserves with plenty of room for expansion.

While some major nations’ gold holdings are reaching 70-80% of their reserves, the head of foreign exchange reserves management for the Central Bank of Hungary, Róbert Rékási, doesn’t think that nations are approaching a ceiling for this figure, and that central banks are still willing to increase their gold exposure.

China and Russia’s 20-year accumulation

The two nations that have increased their gold exposure the most over these past two decades have been China and Russia, which have purchased 1,553 tonnes (393% increase) and 1,873 tonnes (443% increase) respectively.

These aggressive purchases highlight a potential distancing from a weakening U.S. monetary system. The U.S. dollar was recently overtaken by gold as a percentage of Russian reserves, and has fallen to 25-year lows in global central bank foreign exchange reserves.

As both China and Russia have begun preparing central bank digital currencies, the two nations could be looking to set new monetary standards and strengthen their roles in the world’s evolving financial system.

The next 20 years of gold reserves

Gold’s value has stagnated over the past few months while bitcoin and equities have taken the spotlight, however, central banks still consider it an essential part of their reserves.

Developing nations and global heavyweights like Russia, China, and India have all been accumulating and prioritizing gold production, and while European countries have sold some gold the past two decades, they still rank among the largest holders of the precious metal.

As central bank digital currencies loom on the horizon, gold still plays an essential role in the composition of national central bank reserves backing these new financial systems, providing a familiar inflation hedge for central banks and investors in these uncertain monetary times.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments