Vanishing LME shadow stocks add to metals market turmoil

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

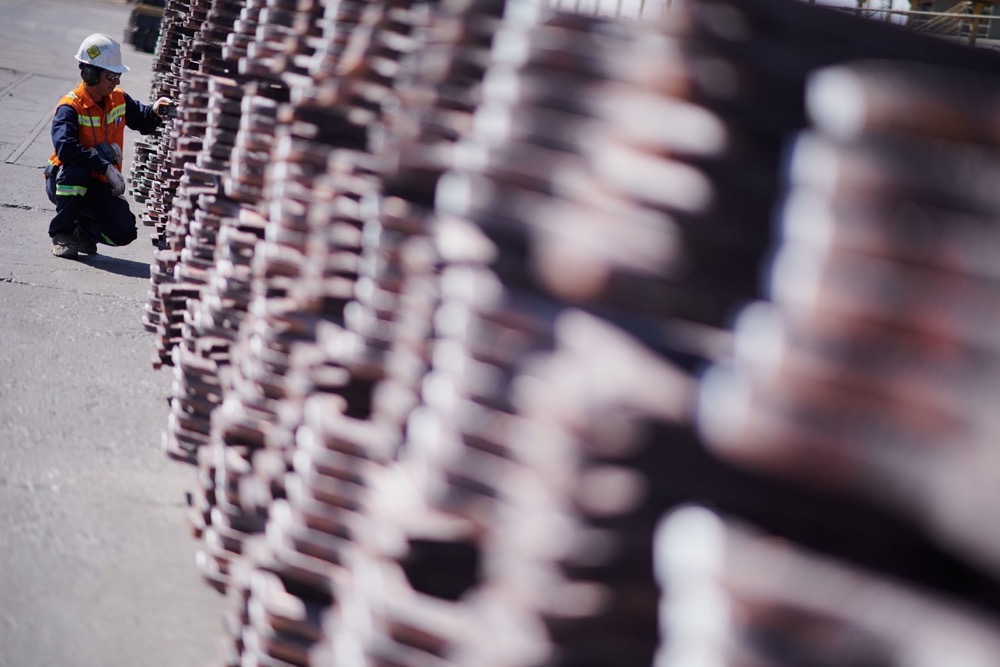

The total amount of registered metal in the London Metal Exchange’s (LME) global warehouse network fell below 1 million tonnes in March.

Exchange stocks of aluminum, copper, lead, nickel, tin, and zinc haven’t been this low since the last century.

The visible clear-out has been accompanied by an even bigger swoop on LME shadow inventory – metal stored off-market but under a warehousing contract explicitly allowing for full exchange delivery.

What the LME calls off-warrant stocks totaled just 256,000 tonnes at the end of February, down 88% on the 2 million tonnes of metal sitting in the shadows a year earlier.

The evaporation of this buffer stock means any call on metal from the market of last resort must be made on the dwindling volume of registered inventory.

It helps explain why the 145-year-old dame of industrial metals trading has been swamped by ever greater waves of market turbulence, culminating in the March suspension of the nickel contract.

Going, going…

When the LME first started publishing its monthly off-warrant stocks report in February 2020, it shone a light on 971,145 tonnes of metal hiding in the warehousing shadows.

At their peak a year later shadow stocks totaled 2.09 million tonnes, slightly more than registered inventory.

Much of the metal stored in this twilight zone has been aluminum oscillating between on- and off-market storage in search of the best financing and warehousing deals.

Shadow aluminum stocks peaked at 1.74 million tonnes in February 2021. By the end of February this year they had shrunk to just 218,000 tonnes.

The scale of the decline argues against this being a case of owners opting to move metal away from the exchange’s warehouses to avoid statistical scrutiny. Rather, it suggests radically changed market dynamics.

Firstly, aluminum is now much more valuable as a physical unit. It is commanding a premium over LME cash of around $600 per tonne in the European duty-paid market and almost $900 in the United States Midwest.

Secondly, the draw on LME stocks has tightened up the forward curve, meaning fewer spread opportunities for lucrative stocks financing deals.

The value of stockpiled aluminum, in other words, is now greater in the physical supply chain than in the financial arena and metal has been leaving exchange warehouses accordingly.

It makes sense that shadow stocks have been drawn down faster than on-market stocks because they are less sticky, not requiring an on-exchange trade and warrant cancellation to physically move into the supply chain.

The fact that both shadow and registered aluminum stocks have been falling in tandem is a sign of an under-supplied market.

China, the world’s largest producer, imported almost 2.65 million tonnes of aluminum over 2020 and 2021, draining the rest of the world’s surplus inventory.

What remains is being fed into supply-chain gaps created by lower production in Europe as the region’s smelters struggle to cope with runaway power prices.

No safety net

Shadow stocks of other metals have nearly disappeared.

Off-warrant copper inventory collapsed from 175,000 tonnes in February 2021 to just 18,352 tonnes at the end of February this year.

Nickel stocks have similarly crashed, from 44,000 tonnes to 2,428 tonnes over the same period, while lead stocks totalled a meagre 547 tonnes at the end of February.

Anyone looking for extra zinc a year ago would have been able to tap 87,000 tonnes of shadow stocks. That buffer inventory has fallen to 15,261 tonnes, most of it in the LME’s Asian warehouses.

That explains why LME on-market zinc stocks have been raided to the tune of 60,000 tonnes since the start of April.

Smelter curtailments in Europe have deepened the regional deficit and sent physical premiums soaring. With LME shadow stocks now almost fully depleted, the only source of accessible replacement metal is the zinc sitting on LME warrant.

The pressure on LME zinc stocks has inevitably tightened time-spreads and sent the three-month price surging higher, last trading at $4,500 per tonne.

With available live tonnage in the LME system standing at 45,925 tonnes, the market is now super-sensitive to further cancellations.

Stock out

The LME’s physical delivery function is doing what it’s supposed to do during times of market shortfall.

Pandemic lockdowns, logistics disruptions and smelter cutbacks in Europe have generated a massive supply-chain storm for industrial metals.

LME stocks have been drawn down to fill the resulting supply gaps, particularly in Europe.

But the result is higher pricing and heightened volatility.

The tiny LME tin market has been operating on super-low stocks for many months now.

There has been some recent rebuild to 2,665 tonnes as a result of warranting at Antwerp and Baltimore. But that’s still equivalent to under three days worth of global usage and there were only another 85 tonnes of shadow stocks as of February.

Tin is a stocked-out market and the result is historically unprecedented price strength, with LME three-month metal currently trading at $42,800 per tonne, and regular bouts of time-spread tightness.

If current trends continue, tin is not going to be the only LME metal to be defined by physical scarcity.

(Editing by Mike Harrison)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

OTOH/IMHO

“Exchange stocks of aluminum, copper, lead, nickel, tin, and zinc haven’t been this low since the last century.” Well, if the exchanges can force cash settlement for futures contracts(or better yet, fail to investigate massive naked short selling) who needs stocks at all?[sarc]