Vale misled public on dangerous dams, prompting Brazil probe — source

Faced with public outrage after its second mining dam collapse in four years killed at least 240 people in Brazil, Vale SA misrepresented what it had done to shut down its riskiest dams, a review of the company’s statements shows.

Fabio Schvartsman, Vale’s then-chief executive, said at a nationally broadcast news conference days after the dam burst in late January that the company had already decommissioned nine “upstream dams” in the wake of a 2015 disaster involving the same type of structure, and planned to dismantle 10 more over the next few years. The company repeated the claim in a statement on its website.

Prosecutors are looking into ex-CEO Schvartsman’s declaration that Vale had already shuttered nine upstream dams in response to the 2015 collapse

Reuters asked Vale for details on these moves on February 5, seven days after Schvartsman’s news conference.

In March, some five weeks later, Vale gave Reuters a list of nine dams that it said it had closed since 2014, a year before the Mariana disaster. They all were smaller structures and not the dangerous upstream type, according to Eduardo Leão, a director of the Brazilian mining regulator ANM, and another expert who reviewed the list for Reuters. Vale also listed the 10 dams that it said it planned to close, including the collapsed one at Brumadinho.

Brazilian prosecutors now are looking into Schvartsman’s declaration that Vale had already shuttered nine upstream dams in response to the 2015 collapse as part of a wider criminal probe into the company’s conduct, an individual close to the investigation said. The widening of the probe has not been previously reported.

The 2015 collapse, at its Samarco joint venture with BHP Group, killed 19 people near the town of Mariana.

“There was a lot of talk about measures being taken to avoid a repetition of what happened, but it was nothing more than talk,” the source added.

Schvartsman’s representatives at the law firm of Bottini & Tamasauskas declined to comment.

In a statement, Vale said the original figures that Schvartsman provided were based on “information available at the time, provided by employees from the company’s ferrous metals area at the time of the (news conference) and that it had later sent revised data to Reuters and other news outlets.”

Vale said its statements surrounding the dams had been made in good faith, and added that it had done a lot to prevent a recurrence of the Mariana disaster and that much “is still being done.”

The latest development adds to the mining giant’s legal troubles. Brazilian prosecutors have said they are looking into whether senior Vale executives were aware of stability issues at Brumadinho and other dams but failed to disclose them or take adequate actions to resolve them.

Brazilian market regulator CVM has also opened at least two different administrative probes into Vale’s handling of the disaster, while the company faces U.S. class actions and at least one investor arbitration case in Brazil.

Mining watchdog ANM is carrying out a separate investigation into the causes of the dam burst as well as whether any mining or other administrative rules were broken.

“In my view, it’s clear that the CEO of any company, public or private, will certainly be held accountable by shareholders and the authorities for any kind of statement, especially if it is proven to be untrue,” said Luigi Bonizzato, a professor of constitutional law at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Different dams

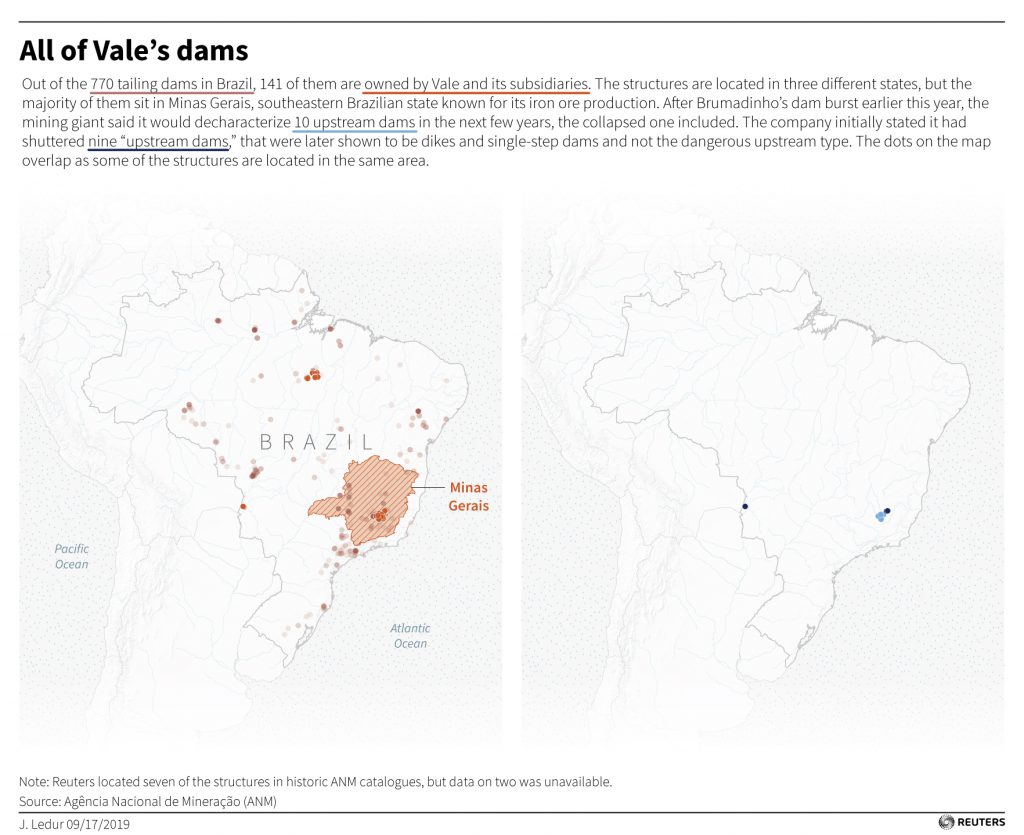

Vale operates several different kinds of dams in Brazil to store the muddy detritus of its mining activity known as “tailings.” The two that collapsed used an upstream technique in which the dam is gradually built upon a reservoir of sludge.

Such dams are generally cheaper to build, but they run a higher risk of water seeping under the dam and weakening the structure, mining experts told Reuters.

Chile and Peru have long banned the construction of such dams, because of the risks of collapse. In February, Brazil’s ANM banned new upstream tailings dams and told miners they had to decommission existing ones by Aug. 15, 2023, a deadline it recently pushed back by as many as four years.

In May, the company told investors that it expected to spend $1.855 billion to shutter the 10 upstream dams it planned to close

Vale, the world’s largest iron ore exporter, is not the only big miner that operates upstream dams. At BHP, for example, 43% of its 67 operated dams are upstream, although only five of those are active, according to a slide presentation on its website from June, with the sole active ones among those based in Chile and Australia. BHP verified that the numbers were accurate.

Schvartsman was removed from the CEO job in early March at the urging of prosecutors who said in a letter to the board that his and other top Vale executives’ continued presence at the company posed “immeasurable risks to society.”

In May, the company told investors that it expected to spend $1.855 billion to shutter the 10 upstream dams it planned to close.

For now, the company’s dams continue to pose risks. In May, one of the upstream dams slated to be decommissioned, called Sul Superior, came close to breaking, Brazilian regulators and Vale said, threatening to force the evacuation of 10,000 people from three historic towns.

Vale said the dam at that mine, known as Gongo Soco, was being monitored in real time by systems capable of detecting millimetric movements, as well as by drones. It added that the company in May started building a concrete containment wall 6 kilometers downstream from the dam that would be able to hold back a large portion of the tailings if the dam collapsed.

(By Marta Nogueira, Jake Spring and Christian Plumb; Editing by Amy Stevens and Paritosh Bansal)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments