US risks stoking inflation if carbon-linked tariffs hit China

China’s steel and aluminum exports are under attack once again, as the US and European Union weigh new tariffs linked to carbon emissions.

The idea from President Joe Biden’s administration would probably have the biggest impact on the aluminum market, particularly in the EU, which has relied on Chinese smelters to plug gaps in output following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That dependency highlights the inflationary risks of any measures that would shrink supply or add costs based on climate goals.

“This is Biden potentially stoking inflation, damaging global trade and certainly not helping Sino-US relations,” Paul Gambles, MBMG Group co-founder and managing partner, said in an interview with Bloomberg TV. “It’s a triple whammy.”

The EU is already considering a carbon tax on imports including steel and aluminum, and China is the biggest producer of both metals. It exports its surplus, at times drawing accusations that Beijing is swamping the world market to the detriment of other suppliers. It’s also the world’s worst polluter. The steel industry is China’s second-biggest emitter after electricity generation, and combined with aluminum accounts for about one-fifth of the nation’s carbon.

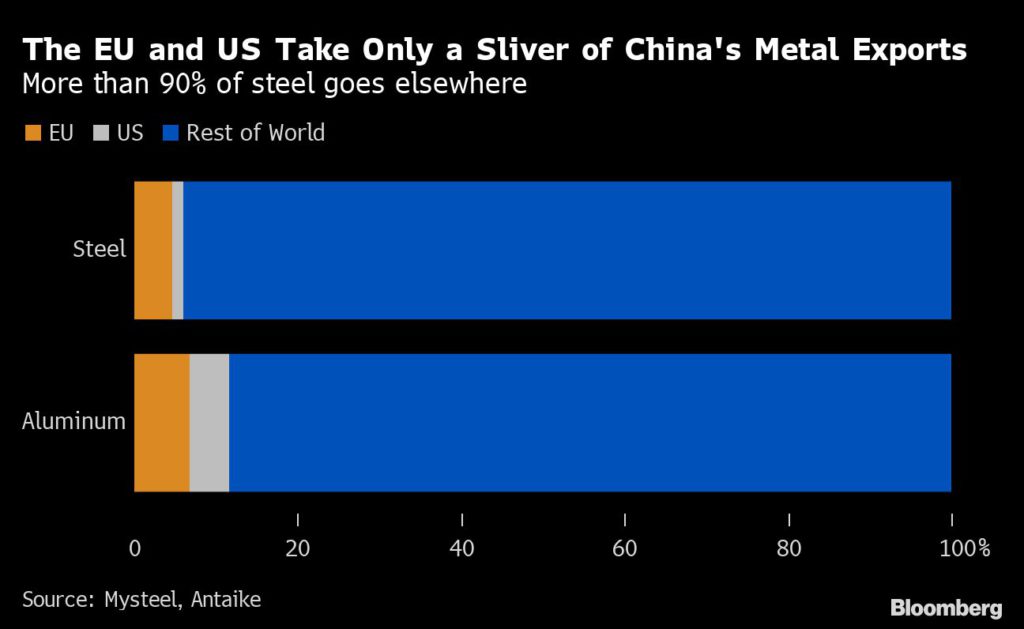

China’s steel exports peaked in 2015 at 112 million tons, earning a slap-down from the G-7, but are now running at about half that amount. Just a sliver of that ends up in the US and EU. Existing protectionist measures cut sales to the US to less than 1 million tons in 2021, just 1.3% of China’s total exports of the alloy, according to research firm Mysteel.

More steel — just over 3 million tons last year or 4.6% of exports — is sold to the EU. “Potential tariffs will have a bigger impact on high-end steel products exports to the region,” said Mysteel analyst Xu Xiangchun. “Mills making high-end steel products are likely to be hit.”

Overseas aluminum sales, meanwhile, hit a record of 677,000 tons in May, with much of that taken up by Europe as its own smelters shuttered because of the spike in energy costs caused by the war in Ukraine.

It’s unclear how measures to tie exports to climate goals would change China’s tack on steel. While individual steelmakers have invested heavily in greener technologies, the industry as a whole has been backsliding. Investments in new coal-based blast furnaces increased in the first half of 2022, a development that isn’t compatible with Beijing’s carbon policies, according to a report last month by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

While tougher rules on CO2 helped cut steel output in 2021 from record levels, and a similar drop in production is expected for 2022, the government has delayed its deadline for the industry to peak emissions by five years to 2030, highlighting once again the importance of infrastructure spending to its economic goals. More such stimulus could be on the way in coming months as the government seeks to buttress a slowing economy.

Aluminum output, however, is becoming greener as more hydropower is deployed to replace coal, said Xiong Hui, an analyst with Beijing Antaike Information Development Co.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments