US coal plants’ fate hinges on June power-price auction

Some of the country’s oldest and dirtiest coal power plants will be forced to consider whether to shut their doors once and for all when the results of a key price auction on the largest US grid are announced next week.

Suppliers to the grid stretching from New Jersey to Illinois will find out on June 21 whether their bids to provide backup capacity for the year starting June 2023 passed muster. If they bid low enough to win a contract, a big chunk of their revenue is locked in. If high operating costs meant their bids were too pricey, some plants serving the PJM Interconnection LLC grid might decide it’s no longer viable to churn out power.

Nuclear plants backed by subsidies, new natural gas plants and many renewable-power facilities are the most likely to fall into that first camp — auction winners — given lower costs. Older, less efficient plants, including some coal plants that didn’t lock in cheap fuel contracts, are likely to land in the second, putting them at higher risk of shutting down.

“The absence of capacity revenue could be really tough on coal plants,” said Steve Piper, director of energy research at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

Although the average consumer may not give much thought to capacity auctions, the annual event is important. The market, which pays generators to be on standby in case the grid suddenly needs power, is a crucial tool for keeping the lights on for more than 65 million people in 13 states. And since it provides a steady source of income that can make or break power plants, the auction plays a central role in shaping the US energy landscape.

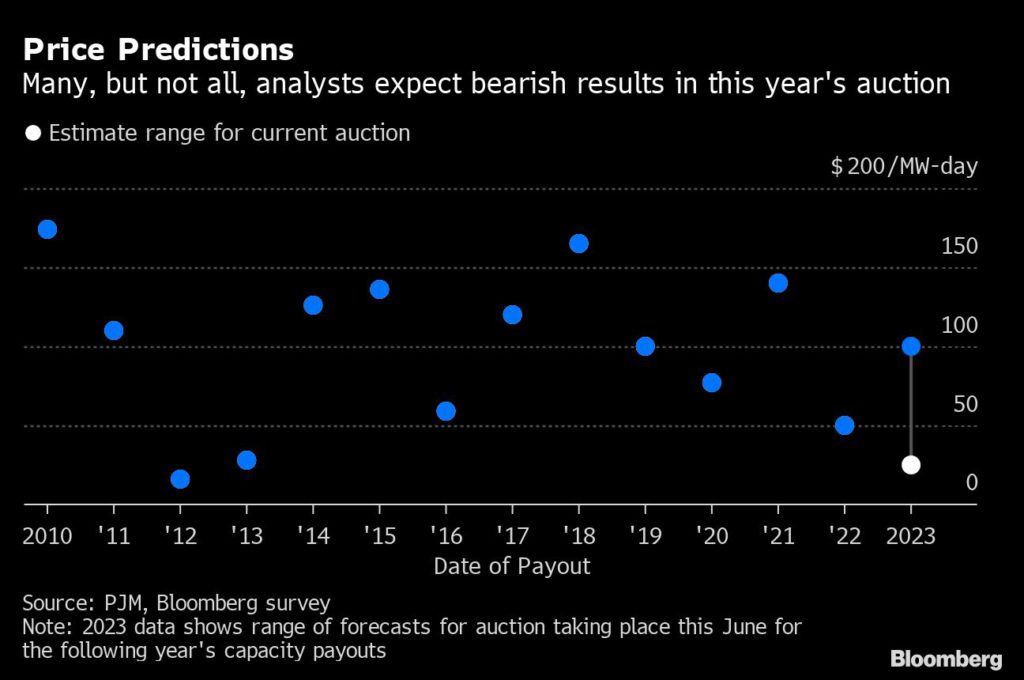

Analysts and market observers are split on how the auction will turn out. Last year, prices in the capacity auction plunged to $50 a megawatt-day, the lowest price in 11 years. S&P’s Piper, the most bearish respondent in a Bloomberg survey, expects the rate to collapse even further this year, to $25, which would be the lowest since the 2009 auction, which set prices for 2012.

PJM’s auctions have traditionally been held several years in advance so power-plant owners have time to make investment decisions, though lately, the price has only been determined one year out, meaning it’s harder to predict what kind of response companies might have if their bids are unsuccessful.

Most other respondents also expect a somewhat bearish trend in capacity payouts for the year starting June 2023, though that downward forecast is by no means unanimous. One contrarian even sees prices rising as high as $100.

These costs ultimately show up on monthly electricity bills for households and businesses, though it’s just one of many components. That means lower capacity prices don’t necessarily mean cheaper consumer power bills.

Not all markets use capacity auctions to guarantee backup power, most notably the one serving most of Texas. It relies on market forces — in other words, high power prices — to encourage generators to be ready when the grid needs them most. Officials in the state have long argued that’s ultimately cheaper for consumers. But critics warn that the strategy brings major reliability risks as climate change leads to more outages. After last year’s deadly — and costly — blackouts, Texas regulators are now considering a form of capacity payments.

For those expecting prices in the PJM auction to fall, they’re primarily looking at the return of very low-cost Illinois nuclear units that won state subsidies to keep zero-carbon power online and save thousands of jobs. Those plants, now owned by Constellation Energy Corp., are widely expected to place low enough bids to ensure capacity payouts after being blocked for years pre-subsidization because of high costs.

In total, about 6.25 gigawatts of nuclear and new gas-fired generation likely participated in this year’s auction that wasn’t there before, said Toby Shea, an analyst with Moody’s Investors Service. On top of that, PJM has forecast that peak power demand will fall 0.4% next year.

One thing’s for sure though: If prices do come down, it will likely be harder for some high-cost coal plants to compete. There are nearly three dozen smaller coal plants with 2.23 gigawatts of combined capacity — so-called peaker plants that usually only fire up when demand is particularly high — that were already at risk of retirement even before the auction results are announced, the grid’s independent market monitor said in a report earlier this year. A recent run-up in electricity prices has given them a near-term reprieve but it’s hard to predict how long that might last.

In terms of weakening capacity prices, “I think the bearish trend will continue,” Shea said. “Almost all the factors are trending negative or bearish. There are very few factors that would boost the markets.”

(By Naureen Malik and Will Wade)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments