Uranium surges 31% to become year’s top commodity

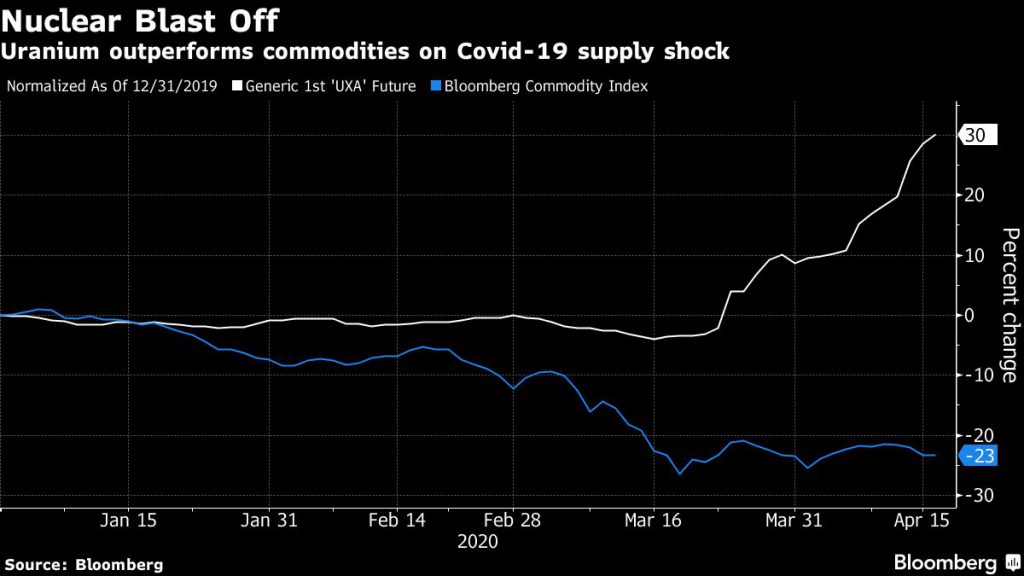

While most commodities are getting hammered by the coronavirus crisis, uranium prices are skyrocketing.

The radioactive metal used in nuclear fuel has climbed 31% this year, making it the world’s best-performing major commodity. The gains have been spurred by mine shutdowns that have wiped out more than a third of annual global output at a time when demand from power plants has remained relatively stable.

“This is a bit of a one-two punch in uranium’s favor,” said Nick Piquard, a portfolio manager at Horizons ETFs. “Not only has Covid-19 likely not impacted nuclear power demand very much, but it is certainly impacting supply.”

While demand for energy, including nuclear, is taking a hit due to the pandemic, many atomic power plants are expected to keep open. That’s partly because coal- and gas-powered plants are easier to turn on and off than nuclear facilities, so it’s worth keeping them running even if electricity demand declines somewhat, Piquard said.

The shutdowns wiped out about 46 million pounds, or about 35%, of annual global uranium output, over three weeks

The uranium industry has been in the doldrums since the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan, which led to the shuttering of most of that country’s nuclear reactors as well as a rethink of nuclear power worldwide. The shift led to a glut of the metal piling up in warehouses, sending prices down by as much as 75% from the highs in 2011.

In response to low prices, two industry giants, Kazatomprom and Cameco Corp., have been curtailing uranium production in the past three years to reduce the global glut.

The Covid-19 crisis has accelerated that process with a jolt. Kazatomprom, the largest uranium producer, announced earlier in April it was reducing operational activities at its uranium mines in Kazakhstan for about three months.

Meanwhile, Cameco further decreased its own output last month by halting production at Cigar Lake in Canada, the world’s largest producing mine — then extended the suspension for an “indeterminate” period on April 13. The company also shut some operations at its Port Hope fuel-service facility for four weeks.

All told, the shutdowns wiped out about 46 million pounds, or about 35%, of annual global uranium output, over three weeks, according to Cantor Fitzgerald analyst Mike Kozak.

As in other countries, U.S. reactors are considered essential infrastructure, and utilities are implementing resilience plans to ensure they remain in operation to keep the power flowing. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued guidance in March for utilities to request longer shifts for workers if needed, and is also letting companies defer some inspections.

“They want to get the entire industry up to maximum power,” said Paul Gunter, a director at Beyond Nuclear, a watchdog organization.

Uranium futures traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange have soared about 36% since mid-March to $32.50 a pound. Equities and exchange-traded funds have followed the rally. Among the gainers, Cameco, Uranium Participation Corp., North Shore Global Uranium Mining ETF and Horizons Global Uranium Index ETF have all risen at least 50% from their March lows.

The increases may be sustainable. The current scenario has the potential to become “the turning point in a 10-year bear market,” Scotiabank analyst Orest Wowkodaw said in an April 13 note.

Fueling the uranium rally is fear of securing future supply. Utilities typically hold 1.5 to 5 years of inventory as a hedge against logistical hiccups to keep power flowing. More recently nuclear utilities, the biggest customers, have been able to top off their needs through excess inventories built up around the world.

But with several supply and price shocks hitting the market all at once and inventories already low, uranium customers such as utilities may “scramble to secure material,” said Cantor’s Kozak.

Spread of the pandemic has slowed ships, trucks and planes that shuttle commodities to consumers from their suppliers.

“We have been saying for some time that although inventories in our industry can appear high, it is the mobility of inventories that is important,” Cameco spokesman Jeff Hryhoriw said in an email. “That we believe will be the focus during this unplanned event.”

And the situation could get worse. “History would suggest that mobility decreases in a rising-price market as security of supply concerns set in,” Hryhoriw said.

(By Aoyon Ashraf and Joe Deaux, with assistance from Will Wade and Reg Gale)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments