Uranium price surges to highest since Fukushima on Russian war

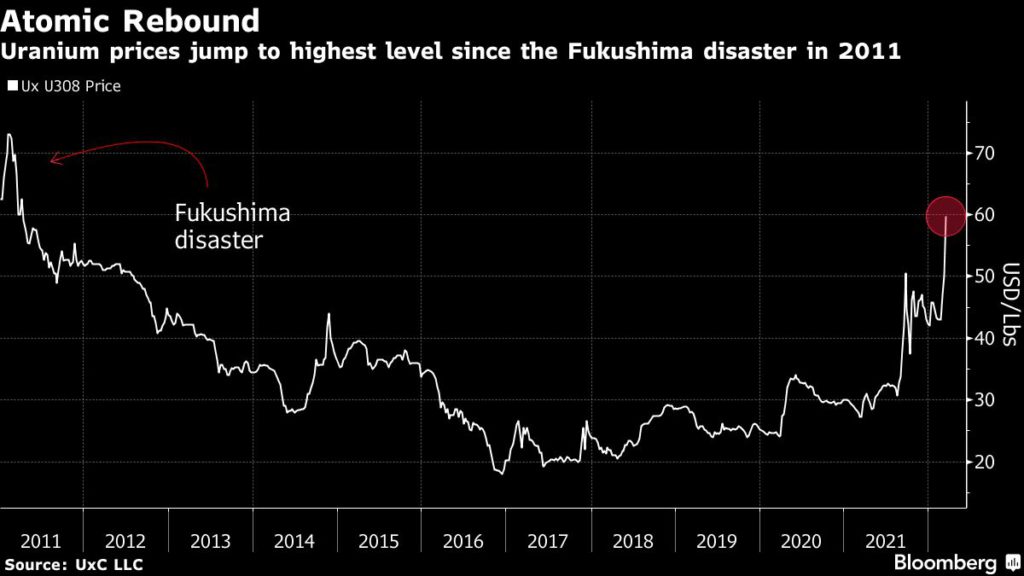

Uranium spot prices soared to the highest level since the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster on concern potential sanctions aimed at Russia are poised to roil an already tight market.

The price for benchmark uranium jumped to $59.75 per pound on Thursday, according to data compiled by UxC LLC. That’s the highest since March 2011, when meltdowns at the Fukushima Dai-Ichi facility shut Japan’s fleet of nuclear plants, sent a shock-wave across the atomic industry and dashed demand for uranium — the fuel used in reactors.

The White House is considering sanctions on Russia’s state-owned atomic energy company, Rosatom Corp., intensifying concerns over disruptions to uranium exports from Russia. Rosatom is a delicate target because the company and its subsidiaries account for more than 35% of global uranium enrichment. Russia accounted for 16.5% of the uranium imported into the US in 2020.

“The fear of Russian nuclear fuel supplies being cut off in the West (especially the US and European Union) has led buyers to enter the spot uranium market over the past two weeks,” said Jonathan Hinze, president of UxC. “As the prospects for future limits on Russian enriched uranium imports in the West remain high, it appears that this upward pressure on spot uranium prices is unlikely to let up.”

The Sprott Physical Uranium Trust, a fund that has been aggressively cornering the physical market for the metal, has been actively snatching supply since last month, adding to the bullish sentiment. The fund has boosted its holdings of uranium by more than 10% in the last month.

Uranium is the latest raw material to be swept up in the global commodities price rally after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. International backlash and Russia’s sudden economic isolation is choking off a major global source of energy, metals and crops.

To be sure, it’s unlikely that an actual shortage of uranium will develop that forces nuclear power plants to curb output, even if Russian supplies are taken off the table. Cameco Corp., one of the world’s largest suppliers of uranium, could boost output if prices improve enough to warrant additional production over the long-term, according to a spokesperson.

There is “significant potential to increase uranium production outside of Russia,” said Jonathan Cobb, a senior communication manager at the World Nuclear Association. “Nuclear plants typically have enough fabricated fuel on site to keep operating for at least a year, and in many cases much longer.”

(By Stephen Stapczynski, with assistance from Joe Deaux)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments