Uranium & nuclear power play a critical role in the US

Nuclear power meets approximately 20% of U.S. electricity demand. However, what is more notable, is that nuclear power generates more than 50% of the carbon-free electricity in the U.S.1 As the country and the world take steps to tackle greenhouse gas emissions, we believe that nuclear power will continue to be a critical part of the solution.

Uranium is key to nuclear power

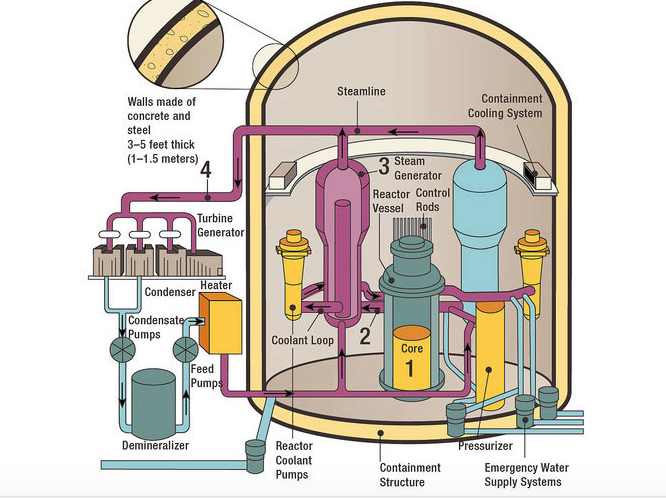

As background, nuclear power stations in the US and worldwide rely on the fission of uranium atoms to create heat. Nuclear reactors use uranium fuel that is assembled so that a controlled fission chain reaction can be achieved. The heat created by splitting the uranium atoms, typically the type known as U-235, is then used to make steam which spins a turbine to drive a generator, producing electricity.

Most U.S. reactors use enriched uranium as their fuel source. Natural uranium in the form of U3O8 concentrate, also known as yellowcake, is refined and then enriched to boost the level of the U-235 isotope from 0.71% up to 3-5%. The enriched uranium is converted into powder, which is then pressed into small ceramic fuel pellets stacked together into sealed metal tubes called fuel rods. Control rods, usually made of boron, help control the fission process, along with water.

Figure 1. A typical pressurized-water reactor

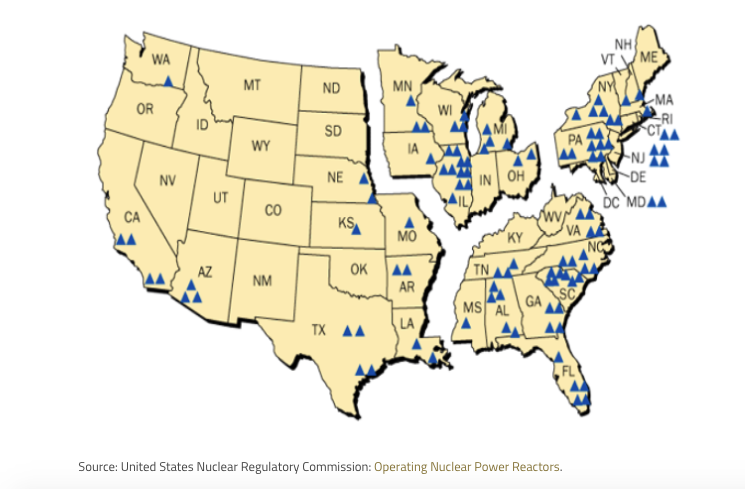

Mapping U.S. Nuclear Power Plants

To understand the dynamics of nuclear power in the American utility market, it helps to review the history of nuclear energy in the U.S. and the footprint of nuclear plants in operation today.

According to the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC),2 the U.S. currently has 94 nuclear reactors operating at 56 power plants in 28 states. Most of the plants are east of the Mississippi River, and many are located on coastlines to take advantage of the cooling power of natural bodies of water.

Figure 2. Distribution of US nuclear power plants in operation today

The first light bulb powered by nuclear energy lit up in 1948, thanks to a prototype nuclear reactor in Tennessee. By 1951, a bigger experimental nuclear reactor, located in the desert in Idaho, successfully created more substantial batches of electricity. By 1955, the first operational plant was generating enough electricity to power the small town of Arco, Idaho.

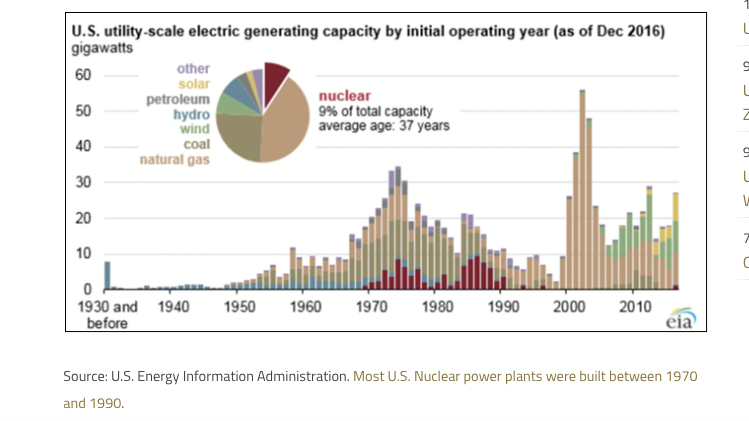

Following these successes, the 1960s saw a push to commission additional nuclear reactors. Utility companies viewed nuclear power as an economical option, in addition to being a cleaner form of energy. Rising commodity prices in the early 1970s supported the popularity of nuclear. The oil embargo of 1973 was a catalyst to sign even more reactor deals as Americans lived through oil shortages, high energy prices and the other costs of foreign energy dependence. 1973 marked the peak of new reactor orders, with 41 orders placed that year. 3

Figure 3. The first era of US nuclear infrastructure: Most plants built between 1970-1990

Changes after three mile island

Three Mile Island was a pivotal point in the popularity of nuclear energy. The partial meltdown of a nuclear reactor in 1979 near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, was the first major global nuclear accident, although it resulted in no deaths or injuries to plant workers or members of the nearby community.4 Dozens of orders for nuclear reactors were canceled following the accident. However, because reactors are built on a long timeline, quite a few were already under construction and came online in the 1980s.

Though popularity dove after the 1979 episode, the incident arose from a design flaw and operator error. Only small changes were made to reactor design in the years that followed, though more substantial changes were made in operator protocols and regulatory oversight. Though public opinion of nuclear declined, safety and reactor efficiency (in terms of the percentage of time that reactors were operating) both climbed substantially.

Nuclear safety

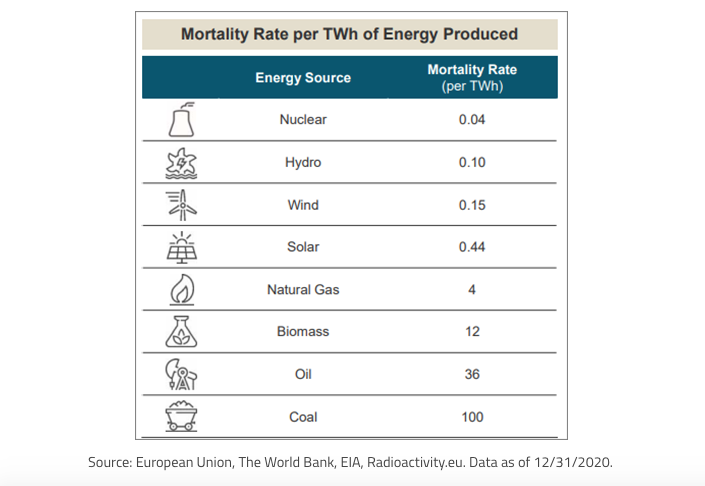

Even our greenest energy sources have negative impacts on humans. These impacts fall into three broad categories: air pollution, accidents and greenhouse gas emissions. Overall, nuclear power is responsible for the lowest mortality rate per terawatt hour (TWh) of energy produced, as shown in Figure 4. Nuclear regulation is ever-evolving and among the most stringent among the energy industries, given its visibility and the weight of public and political opinion.

Figure 4. Global nuclear energy safety

Why Nuclear Plants Are Mostly in the East

Looking at the map of nuclear plants across the U.S., state-by-state factors come into play regarding which states make nuclear power and which do not.

For instance, there are no nuclear plants in western states with access to significant hydroelectric power from dams or other structures around flowing water, including Oregon, Idaho (which shut down early nuclear generators in 1994), Montana and South Dakota. On the other hand, coal-mining states and their immediate neighbors are less likely to have nuclear plants, including Wyoming, West Virginia, Kentucky, Colorado, Utah and Indiana.

Biden’s view on nuclear

The Biden Administration has put environmental concerns at the top of their priority list since the outset. In the energy sector, they have announced a goal to achieve net-zero carbon electricity by 2035, according to Biden’s climate advisor, Gina McCarthy.5

The growth of renewable energy sources, including hydro, wind and solar, contributes substantially toward the net-zero carbon electricity goal. But those sources are not projected to grow fast enough to meet the demand for electricity, plus they generate variable electricity loads based on environmental conditions. Nuclear power, on the other hand, is known for being the baseload provider. Utilities run nuclear reactors around the clock, in part to maximize their economic value – nuclear plants have high capital costs to depreciate but extremely low fuel costs.

McCarthy told the Washington Post in May 2021: “…we do have nuclear facilities that provide significant baseload capacity…we do know that there are many regions in which at least the states themselves feel like the support for those facilities needs to continue while we build an infrastructure of [renewables].”

Support for the existing infrastructure means support for maintenance and upgrades to reactors. Since the wave of nuclear plant building in the 1970s and 1980s, very few new reactors have come online. Most nuclear reactors in the domestic infrastructure are near the end of their 40-year operating license. Fortunately, “uprating” reactors – small improvements to implement technological advances – can extend the productive life of reactors and even bump up their efficiency.

Biden’s team has also expressed support for development efforts on SMRs, small modular reactors. SMR design could potentially cut down on both time and cost to build new reactors going forward.

A valuable source of clean energy

Without nuclear power, carbon emissions from electricity production in the U.S. would have been substantially higher over the last 40 years. To put this in perspective, if the current electricity from nuclear came from coal or oil, it would generate an additional 470 million metric tons of carbon in the atmosphere each year6 – the equivalent of an additional 100 million cars on the road.

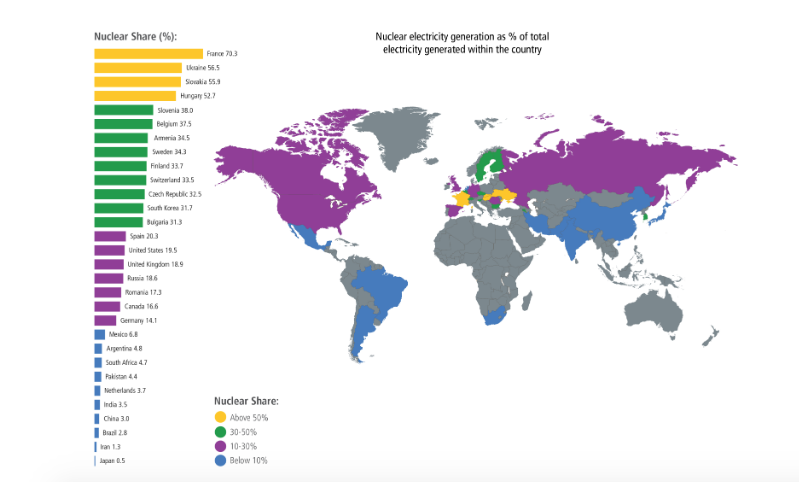

With the drastic improvements in safety and the critically important role of baseload stability, nuclear power offers important benefits to the push for net-zero carbon energy. These characteristics remain important as the country moves toward a higher mix of renewables in its electric grid. Ranked fifteen in the world among countries most reliant on nuclear energy, the U.S. has the potential to expand its nuclear power reliance greatly.

The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that demand for electricity will rise 24% by 2035. The U.S. will need hundreds of new power plants to meet this demand, and these plants will need to take advantage of diverse fuel sources. It is estimated that to maintain nuclear’s 20% share of U.S. electricity generation, 20-25 new nuclear power plants will need to be operational by 2035.

Figure 5. The 30 most reliant countries on nuclear energy: The US ranks #15

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments