Uranium mining in Egypt is expanding despite water contamination, satellite images show

Egypt’s Allouga uranium mine has been expanding despite evidence that its radioactive runoff is contaminating scarce water resources, according to satellite images captured last month for Bloomberg by Planet Labs PBC.

The uranium mine, located less than 150 kilometers (93 miles) from the ongoing United Nations COP27 climate talks in Sharm el-Sheikh, underscores the difficult tradeoffs involved in producing minerals used in zero-emission energy sources such as nuclear power plants.

A peer reviewed study published by Environmental Health Sciences earlier this year sampled uranium levels near Allouga as much as six times the concentration normally found in nature. Egypt’s Nuclear Materials Authority, which owns and operates the site, acknowledged as far back as 2018 that drinking water wells in the area contained “greater concentrations of uranium than acceptable limits.”

“People who are exposed to that level of radiation for a lifetime would have an elevated cancer risk,” wrote the Cairo-based scientists from Ain Shams University who carried out the research, which was published in April. “Available water resources in the study area are considered unsafe for human consumption and irrigation.”

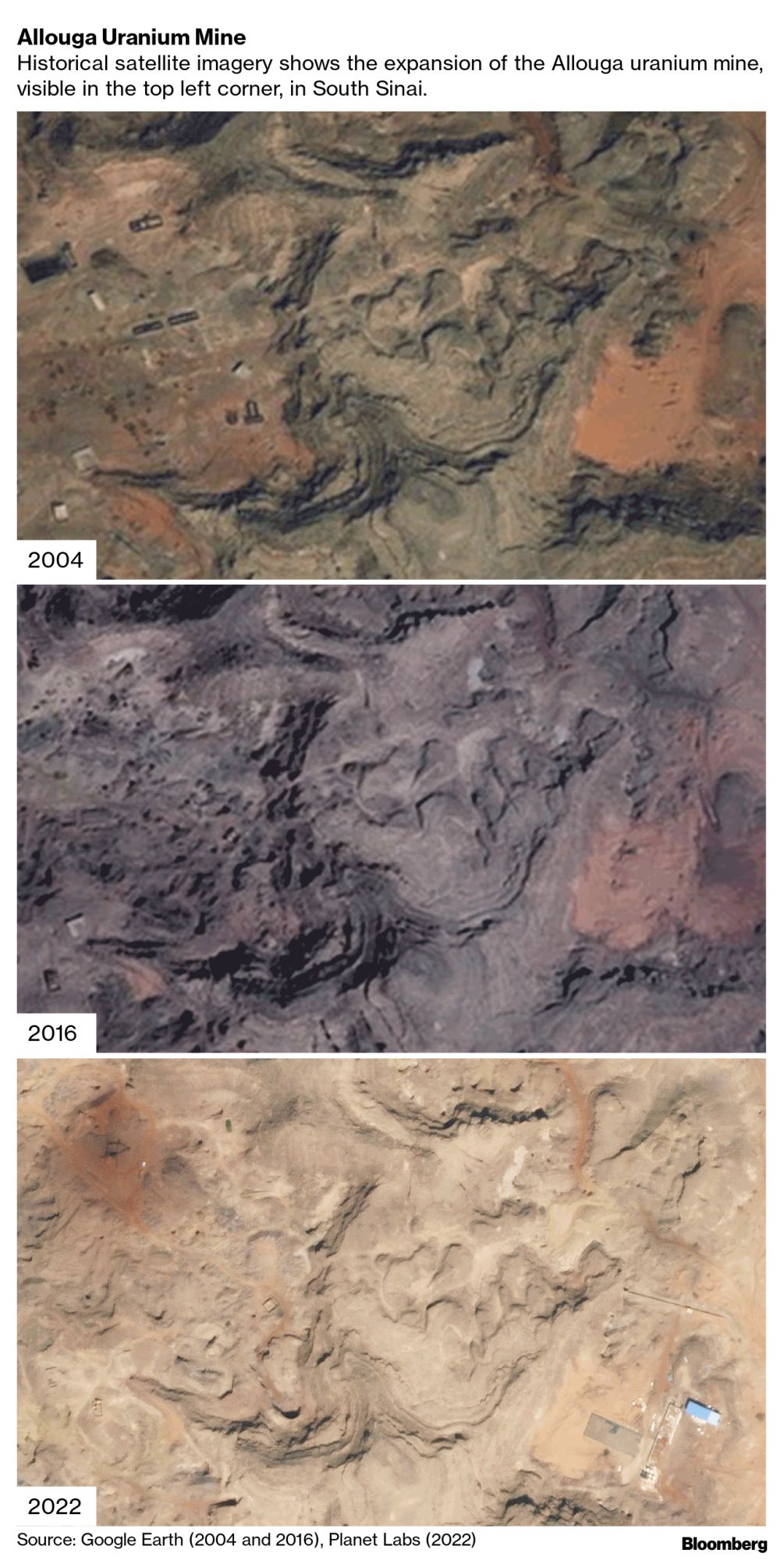

Satellite imagery of Allouga shows how successive waves of excavation and rubble have changed the landscape of the red, craggy hill tops that surround the site over nearly two decades. Ore crushers, processing plants, sulphuric acid tanks and waste repositories appear operational, according to Robert Kelley, a former safeguards director at the International Atomic Energy Agency, who reviewed the photographs. Allison Puccioni, a nuclear non-proliferation imagery analyst at Stanford University, also confirmed activity at the site.

Egypt is estimated by the Paris-based Nuclear Energy Agency to have less than 0.01% of the Earth’s identifiable uranium reserves — not enough to produce commercial quantities it can profitably export. Egypt also doesn’t currently possess the infrastructure to process the ore into fuel for its own future power reactor, which is under construction and will be supplied by Russia.

The small quantities excavated from Allouga could technically be tapped to eventually supply a military program, according to Kelley, a former nuclear-weapons engineer in the US Department of Energy. Egypt is a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and its IAEA envoy, Mohammed ElMolla, dismissed any suggestion it might seek nuclear arms. He said nuclear energy and uranium mining were part of efforts to diversify the country’s energy mix and bolster its economy.

Whatever its purpose, the excavation continues and waste has been dumped on the hillsides.

“A large quantity of mine tailings in the form of slurry waste are placed in small piles adjacent to the mine without engineered barriers,” the researchers wrote. “During the processing, no safety measures were taken to assure the isolation of the tailings from the environment. The major threat of these tailings is the leaching of contaminants (e.g. radionuclides and heavy metals) into groundwater which is considered the main source of drinking water in the area.”

While it warns that the activity needs to bear in mind the impact on local water resources, the study does not present any evidence or make any suggestion that people have been made ill.

The Allouga mine is located in a remote and arid area with no major population centers, mitigating its human impact. The satellite images nevertheless show some small communities, as well as irrigated fields, nearby.

Those most likely to be affected from radioactive effluent leaching into groundwater are local Bedouins, who count among the most vulnerable of the 100,000 people living in the South Sinai Governate, Egypt’s least-populated administrative region. It is the “indigenous community who are principally affected by the mining operation,” according to the Environmental Health Science research.

For the latest study, the authors collected 47 water and soil samples from four wadis — dry valleys that turn into streams after rain — surrounding the Allouga mine and covering an area of some 250 square km.

Egypt’s Central Laboratory for Environmental Quality Monitoring, which analyzed the samples, found most contained uranium concentrations higher than the average two parts per million found in nature. Nineteen of 30 stream sediment samples registered higher-than-normal uranium traces while “all samples’’ of groundwater did, according to the report.

(By Jonathan Tirone, with assistance from Patricia Suzara)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Geoff Russell

This article needs to state clearly what the levels are and what the benchmarks are. Uranium levels “in nature” are incredibly variable. The term is meaningless. Being 6 times higher than the global average sounds extremely small. Say what the levels are. Then compare them to levels allowed in drinking water and name the country whose standards you are using… because the allowed levels are not the same. You need also to consider whether “allowed levels” have anything to do with safety. Mostly they don’t. They are just numbers reflecting easily obtainable levels, not levels that are known to be dangerous when exceeded.