Unrelenting coal demand poses challenge to climate goals

Coal prices across Asia are surging to records, underscoring a challenge for governments seeking a faster energy transition: the dirtiest of fuels they’re racing to phase out is enjoying booming demand.

Power plants are rushing to secure adequate electricity supplies as a hot summer adds to demand from the region’s post-pandemic industrial revival. On top of that, output in some key producer nations has been hurt, while high natural gas costs mean there’s no cheaper alternative for utilities to turn to.

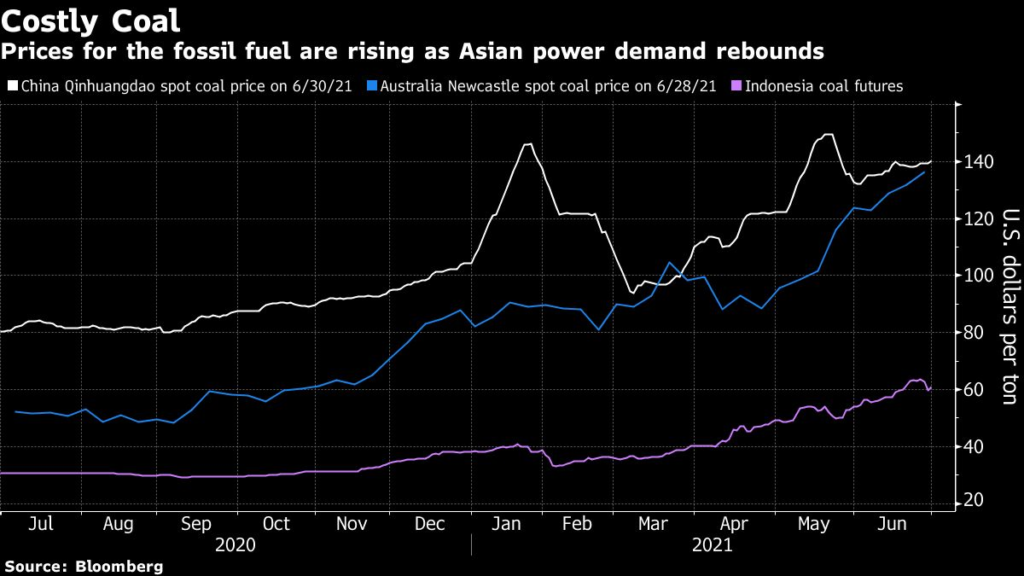

All that has sparked a coal rally in Asia, the center of demand for the fossil fuel. The price of physical coal cargoes in Australia’s Newcastle and China’s Qinhuangdao ports have soared more than 50% this year to their highest ever. Futures are also up, with those in Australia jumping almost 50% and prices in China more than doubling.

“Coal prices just keep on punching higher,” said Sydney-based Peter O’Connor, an analyst at Shaw & Partners Ltd. “We’re close to the top in terms of pricing, but I don’t think we’re there yet.”

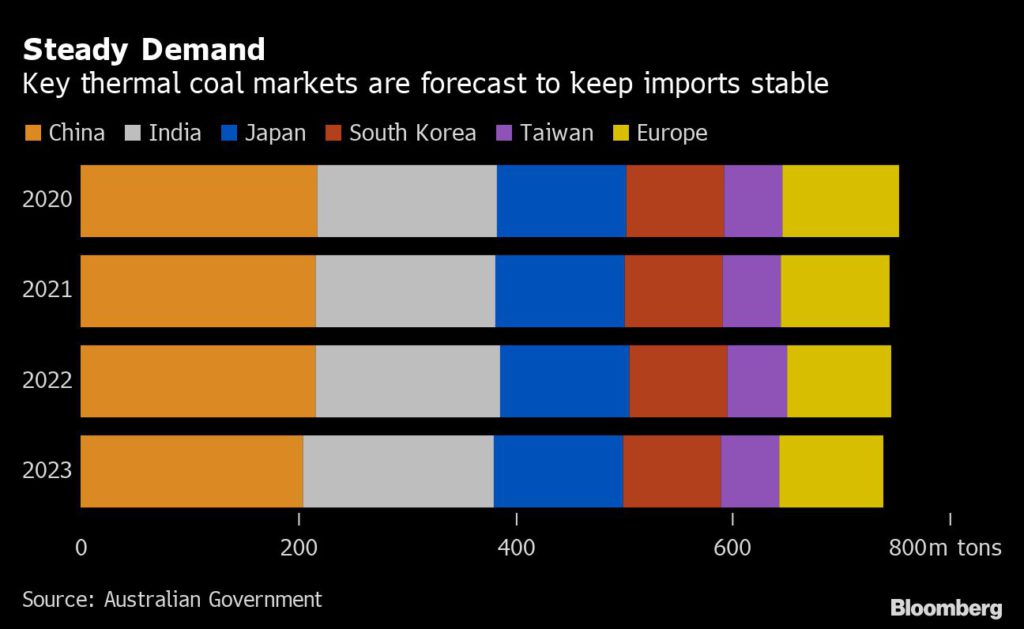

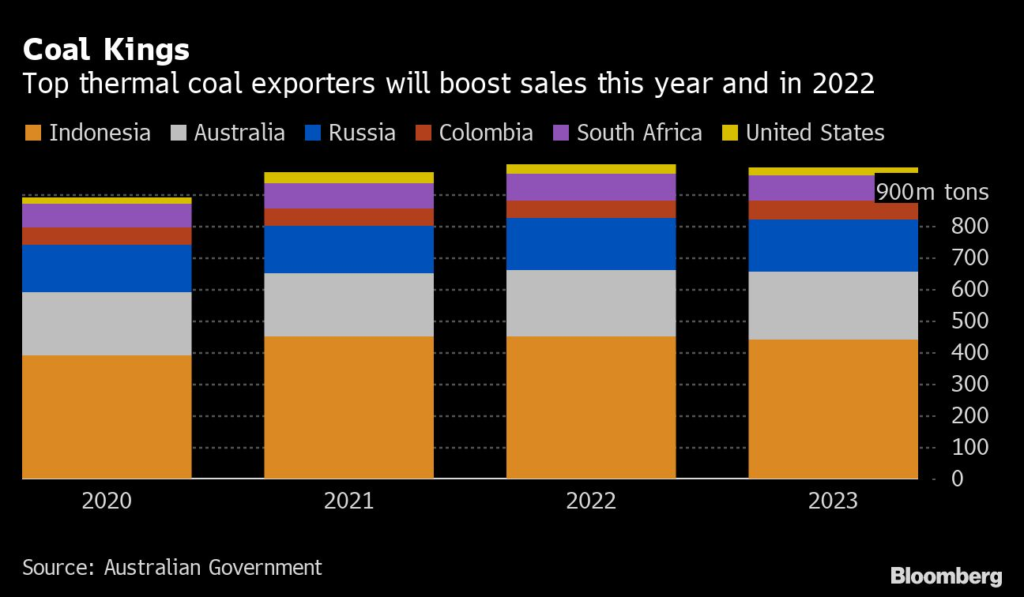

The rally is highlighting coal’s enduring role in the world’s energy mix, particularly in Asia’s large and growing economies, despite a broader push for more aggressive action to tackle climate change. Coal accounted for more than a third of global electricity generation in 2019, according to BloombergNEF. The top three consumers — China, India and the U.S. — are all forecast to burn more this year.

“We can see fairly robust pricing toward year-end,” Sakkie Swanepoel, group manager of marketing at Exxaro Resources Ltd., the South Africa-based miner and coal producer, said on a Tuesday conference call. “We do not see prices just falling off the cliff.”

Here’s what’s driving the rally in key markets:

China

Much of the tightness in the market can be traced back to China, which produces and burns half the world’s supply. Power demand is surging as factories take on orders to supply rebounding economies, and domestic mine output has been slowed by safety inspections after a series of deadly accidents and extra scrutiny because of the Chinese Communist Party’s 100th anniversary celebrations.

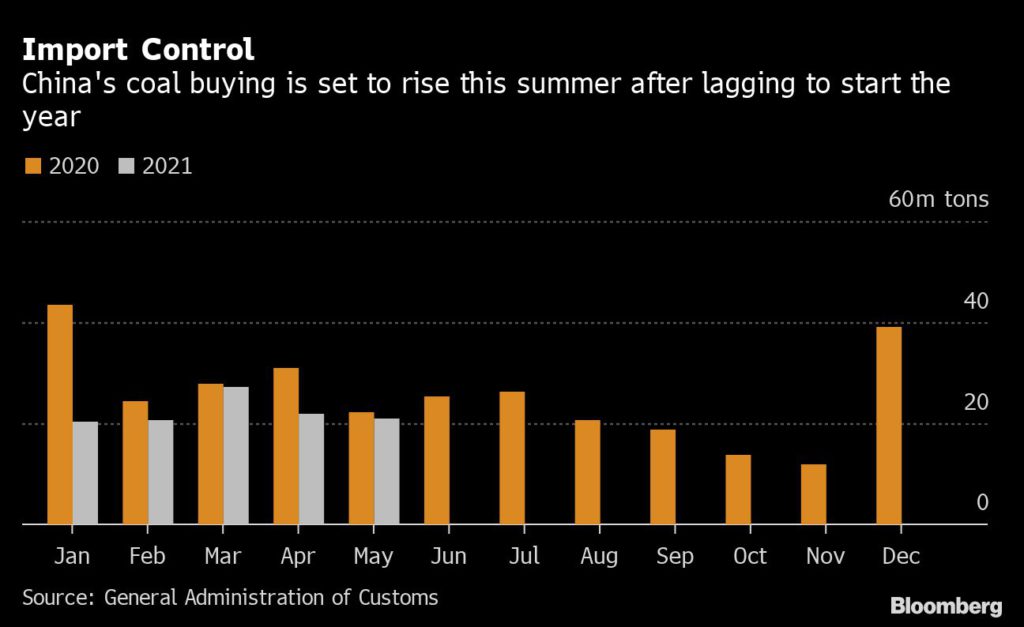

Power plants are looking to imports to fill the gap, with June deliveries expected to top 30 million tonnes for the first time this year before rising again in July and August, according to analysts at Fengkuang Coal Logistics. The country still refuses to allow Australian purchases amid a geopolitical rift.

Even with government efforts to cool the market — such as releasing stockpiles and pressuring state-owned suppliers not to let bidding get out of hand — prices will hold at elevated levels this summer, especially as the spot market is facing a “pretty serious” shortage, said Huatai Futures Ltd. analyst Wang Haitao.

Australia

Producers have shrugged off the loss of a key export market after diplomatic tensions saw China halt Australian coal purchases from late last year. Cargoes of premium thermal coal have quickly found alternative buyers, while suppliers of mid-quality power station fuel and steel-making coal are poised to benefit as India and parts of Southeast Asia ease Covid-related restrictions, Australia’s government said in a report this week.

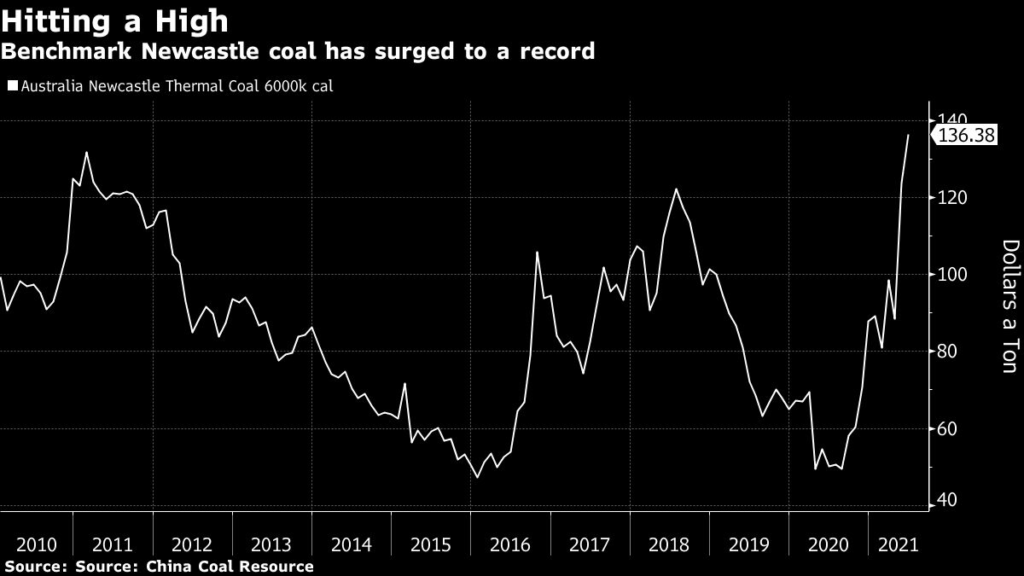

Benchmark prices for higher-quality physical coal at Australia’s Newcastle port have jumped 66% this year to a record of $136.38 a tonne, according to China Coal Resource. Newcastle coal futures on Thursday rose to $131.45 a tonne, the highest since March 2011.

Those gains haven’t translated into advances for some Australian producers. Yancoal Australia Ltd. has declined 18% this year to Thursday’s close, while Coronado Global Resources Inc. has slumped 20%. “Coal is going up, and yet people don’t want to invest in coal,” O’Connor said. “There is a dislocation between coal prices and equities.” Companies including Whitehaven Coal Ltd. have also faced lengthy legal battles over expansion plans.

Japan

Some Japanese utilities have boosted spot coal purchases after the country’s Ministry of Energy, Trade and Industry ordered them to be prepared for summer demand after winter shortages sent power prices rocketing.

Tohoku Electric Power Co. had to agree to a 60% price bump for its annual coal supply through March 2022 from Glencore Plc. Still, the sky-high coal prices are nowhere near the level they would need to be to cause utilities to switch to liquefied natural gas, where prices have risen by 500% in the past year.

Even in the middle of summer, buyers are already negotiating October-loading cargoes as they seek to secure supplies ahead of winter.

Indonesia

Heavy rains in Indonesia in the beginning of the year curtailed supply in the world’s biggest exporter of power plant coal. The government in April gave miners permission to produce an extra 75 million tonnes for export, on top of the 550 million tonnes it had set as a production quota, but so far supplies are behind pace.

“We don’t know yet if the export target can be achieved,” Indonesia Coal Mining Association Executive Director Hendra Sinadia said in an interview. “Even if prices are good it will also depend on demand and economic recovery in buyer countries amid this pandemic situation.”

India

India, the second-biggest coal user, burns the fuel for about 70% of its power needs and higher prices could ripple across the economy, accelerating inflation, according to Rupesh Sankhe, vice president at Elara Capital India Pvt. in Mumbai.

Coal India Ltd., the top global producer of the fuel, is seeking to win sales as customers switch to domestic sources from higher-cost imports. It’s also debating whether to lift prices for long-term contracts to reflect the surge in global benchmark rates, Chairman Pramod Agrawal said last month.

The producer “has a great chance to win back customers that had switched to imports,” Sankhe said.

(By David Stringer and Dan Murtaugh, with assistance from Krystal Chia, Rajesh Kumar Singh, Eko Listiyorini, Miaojung Lin, Tsuyoshi Inajima and Stephen Stapczynski)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Peter A Melville

I’d rather have coal and electricity than chase a theory that has already been proved faulty.