Unexpected bump on the EV road hits battery metals

It’s been a tough year for electric vehicle (EV) metal bulls.

The previous speculative heat surrounding any and every material that goes into an EV battery has dissipated over the course of 2019.

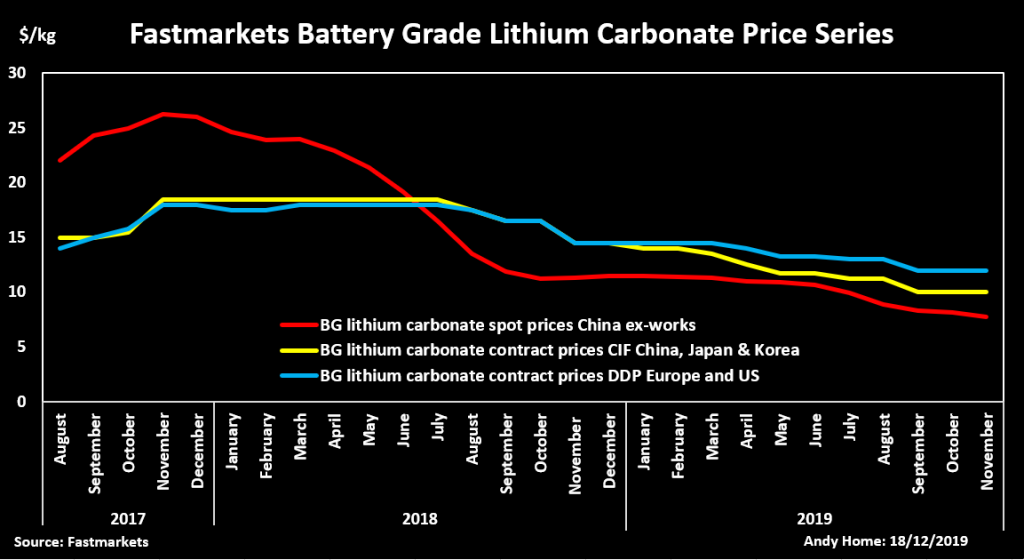

Two years ago the spot lithium price in China was $26 per kilogram. Today it is assessed by Fastmarkets at below $8.

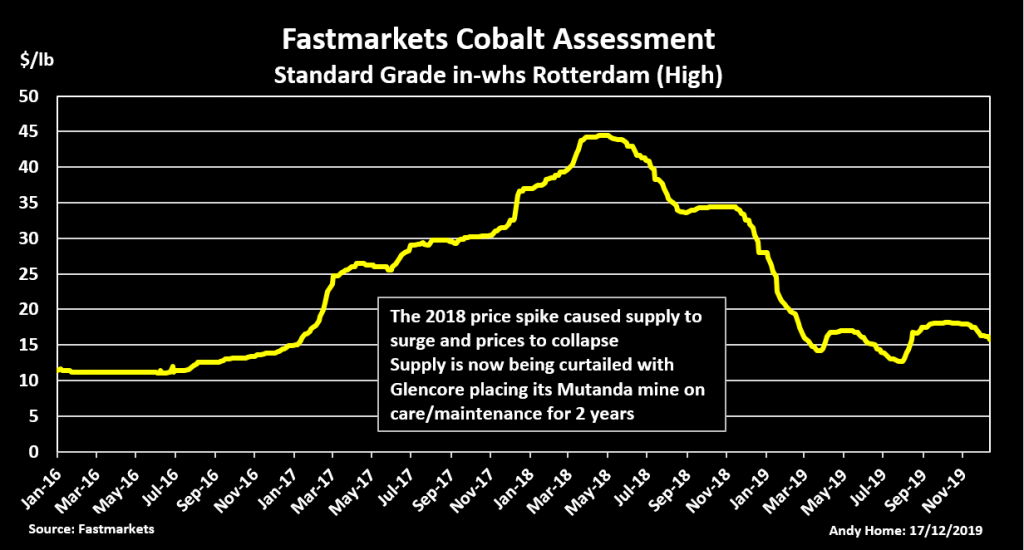

Cobalt, a key input for lithium-ion battery chemistry, has experienced a similar boom and bust cycle, the price of standard grade metal sliding from over $44 per lb in the second quarter of 2018 to a current $15.75.

The EV revolution appears to have stalled this year, challenging previous expectations for future growth

Nickel has fared better but only thanks to strength in its traditional end-use sector, stainless steel, rather than any pull from the battery sector.

Both lithium and cobalt are living with the consequences of previous price exuberance in the form of a supply surge that has swamped processing capacity and left an overhang of stock.

The impact has been accentuated by an unexpected slowdown in demand from the EV sector in China, where sales have fallen for five months and are expected to record a loss for this year.

China accounts for just over half of global EV sales in 2018, according to the Edison Electric Institute.

Global sales of EVs this year through to October have risen 13%, compared with 64% in 2018.

The EV revolution appears to have stalled this year, challenging previous expectations for future growth.

Appearances can be deceptive, however, and there is accumulating evidence that the next demand wave is building.

It’s only a question of when it breaks and washes through the market. And will producers be ready when it does?

As China slows, Europe accelerates

China is at the forefront of the EV revolution and it is weakness in the Chinese market that has caused a collective double-take on the EV story.

Chinese sales of new electric vehicles (NEV) fell by 44% year-on-year in November. It was the fifth straight month of contraction, reducing the year-to-date growth rate to just 2%. There is now the distinct possibility that full-year sales will fall below 2018 levels, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM).

Analysts at Macquarie Bank agree, forecasting NEV sales in China to slide by 6% this year, compared with a previous forecast for 10% growth and actual average growth of 98% in each of the previous four years.

This is part of a broader downturn in the Chinese automotive sector but the specific weakness in EV sales is down to an overhaul of Beijing’s subsidy system in the second quarter of 2019.

It’s not the first time China has rejigged its EV subsidies but it is the first time that sales have been impacted so severely.

The proposed phase-out of subsidies altogether next year threatens more sales disruption but Beijing might well change tack. It has just set a target for NEVs to account for 25% of all car sales in 2025, up from 5% last year.

That’s going to be hard to achieve without some form of incentive scheme.

It’s not the first time China has rejigged its EV subsidies but it is the first time that sales have been impacted so severely

Moreover, next year will see the EV baton pass to Europe, where automakers are now racing towards electrification to beat new carbon dioxide emissions regulations.

Macquarie notes that NEV penetration in the European market was 4% in October, beating China into second place. “We have become more bullish about European prospects for EV sales and now see the region overtaking China in terms of market penetration by 2023,” it said.

A milestone will come with the launch of Volkswagen’s ID.3, a passenger car promising long-range capability at an affordable price.

It will mark the first significant entry by a mass automaker into a space previously dominated by Tesla.

Building the pipeline

Where Volkswagen leads, other European automakers will follow. And they will all need batteries.

The interest in long-term supply deals, such as that just signed between BMW and China’s Ganfeng Lithium belies tepid consumer activity in the spot market.

Investment in battery-cell manufacturing facilities is also surging as the industry builds out the capacity needed to power its electric dreams.

“The rate at which battery megafactories have been announced has dramatically increased over the past twelve months, with the number of factories and capacity almost doubling,” according to analysts at Benchmark Minerals. (“Cathodes 2019: Key Talking Points”, Nov. 21, 2019)

Benchmark Minerals is now tracking 103 megafactory projects with a projected 2,028 GWh of capacity in the pipeline for 2028.

Battery-makers, meanwhile, are shifting towards chemistries that need more metals such as cobalt and nickel, cushioning the impact of falling EV sales in the Chinese market.

The average EV sold globally contained 22% more nickel, 19% more cobalt and 15% more manganese in October than the same month last year, according to Adamas Intelligence.

These underlying drivers of future EV metals demand are still accelerating, even as visible end-user demand in the form of EV sales appears to be slowing.

From glut to shortage?

The current supply gluts in both lithium and cobalt are testament to both markets’ problems in matching output with demand.

“Demand for lithium accelerated much faster than we anticipated back in 2017,” according to Luke Kissam, chief executive of Albemarle Corp, the world’s largest producer.

The ensuing price spike then incentivised too much production, particularly from a new generation of hard-rock spodumene miners in Australia.

Lithium producers are now dealing with the consequences by cutting output and trimming expansion plans.

Glencore is doing the same in the cobalt market by placing its Mutanda mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo on care and maintenance for two years.

Supply discipline should help stabilise prices and erode stocks although most analysts think things could get a little worse before they get better.

Will Adams, analyst at Fastmarkets, for example, is bearish on lithium prices “for most of 2020” and thinks cobalt will be flat at current levels for the first half of next year before rising in the second half.

However, everyone is still bullish on the long-term story.

Albemarle forecasts lithium demand to hit one million tonnes by 2025. It and other established lithium players are confident they can lift production accordingly.

The boom and bust cycle of the last couple of years doesn’t inspire much confidence in producers’ collective ability to manage the next demand surge in either the lithium or cobalt markets.

Many junior miners and exploration companies, meanwhile, have either been forced out of business or gone in search of other metals.

It’s easy to see how current supply feast could easily turn into famine when the EV revolution goes from current pause to fast forward.

We may not have long to wait to find out.

(By Andy Home; Editing by Louise Heavens)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments