UK’s power switch-off shows future for cleaner energy grid

For a few hours last week, British consumers were asked to make a choice: keep consuming power as normal or just turn the lights off.

Hundreds of thousands of households took part in the effort to reduce electricity demand during a couple of hours when energy supplies were forecast to be particularly tight.

There was a financial incentive offered, but there’s more to the emergency measures. They’re a preview of the choices and behaviour that will have to become commonplace as the world transitions its energy supply to depend overwhelmingly on intermittent renewable sources.

Public expectations about the cost and availability of gas and electricity have been upended by the global energy crunch following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Where people once took supplies for granted, the crisis in Europe has exposed a far more fragile system.

In response, countries are trying to speed up deployment of renewable power capacity to better guarantee sources of energy and cut down on greenhouse gas emissions. But this will also require a big shift in deeply embedded habits about how and when people consume power.

“Demand-side response needs to become part of the everyday, part of business as usual,” Sarah Honan, flexibility policy manager at the Association for Decentralised Energy, told a committee in the UK Parliament earlier this week.

Power spikes

Every second of every day, technicians keep the world’s electricity grids in a delicate balance between supply and demand. They keep an eye out for potential spikes, like when everyone has the television on to watch the World Cup or the more regular evening surge when people are cooking dinner.

But rather than just ramping up supply, the UK is trying to shift some demand instead.

Residential electricity suppliers asked eligible customers to use less power than normal for an hour Monday evening and 90 minutes Tuesday. Participants were rewarded with cash for every unit they cut, compared with their typical use.

One major supplier, Octopus Energy, reported that 400,000 customers took part in each session. On Monday, they cut usage by about 200 megawatt-hours of electricity, as if all power was shut off in Bristol, among the 10 biggest cities in England.

The following day, the drop in demand customers was nearly equivalent to the city of Liverpool turning off the lights for an hour. It’s a little less than 1% of total power generation during that period, but enough to make a difference to the slim margins on the grid.

If supplies were really unavailable, then this kind of program could help prevent a calamity. But it’s also a dress rehearsal for a future where wind power plays a bigger role in the grid.

When the wind dips, something else has to fill the void. For the short term, that’s mostly natural gas. But every unit of demand that people can cut is a bit of gas that doesn’t need to be burned and a little less greenhouse gas entering the atmosphere.

Even as countries find low-carbon alternatives to current gas plants, those fossil-based options will be much more expensive. That makes shifts in demand even more attractive.

“It’s a step in the right direction in unlocking cost efficient and clean demand flexibility,” said Kesavarthiniy Savarimuthu, analyst at BloombergNEF. “It’s way cheaper and cleaner.”

The UK isn’t alone. This winter Ireland started a program called “Beat the Peak” to try and get their customers to shift their energy use out of times of day when demand is highest. Last year in California, the grid operator prevented potentially major blackouts by send a text message to customers asking them to cut down electricity in specific windows.

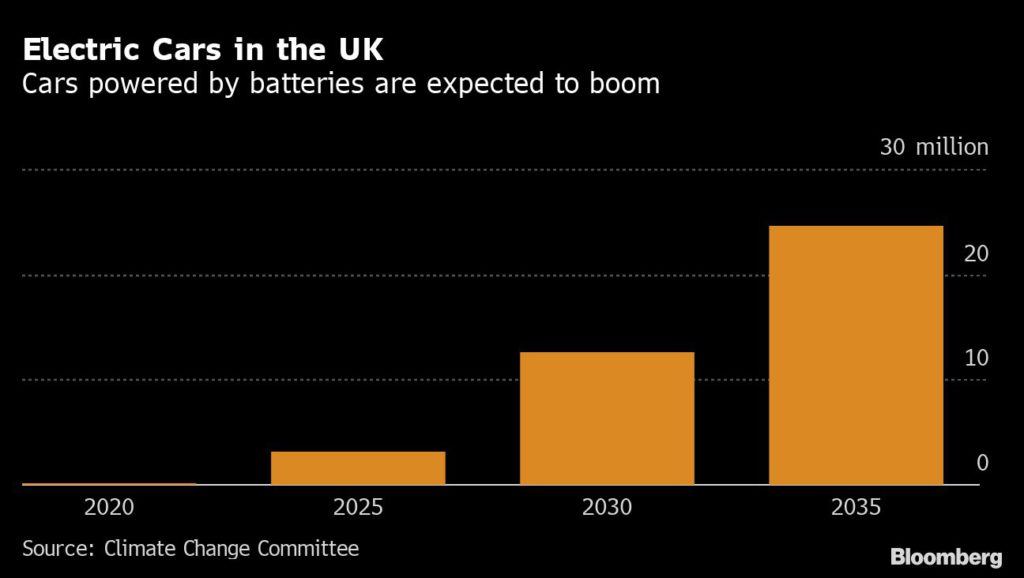

Opportunities will only increase as economies decarbonize. Currently a homeowner might have few options to cut electricity use, but in the coming years more homes will switch to electric vehicles and home heating. Those will add flexibility if people choose to charge up outside of peak hours or turn down the thermostat a bit during demand spikes.

Much of the future flexibility may involve automation that bypasses the challenge of getting millions of people to align power consumption with times when, for example, the wind is blowing and electricity is cheaper.

That could mean homes hand some control of their power use to suppliers, allowing them to do things like lift refrigerator temperatures remotely. Consumers wouldn’t even be aware of the changes.

Key to those efforts will be a modernization of how households communicate with the electricity grid. Traditional meters need to be replaced with smart meters that send real-time data on power usage.

Some places are already ahead on this front. In Denmark, the country with the greatest share of electricity from wind, the majority of households already have a smart meter and people mostly pay market prices for power. That’s a financial incentive for people to shift demand to times when the wind is blowing and prices are lower, often at night.

According to Jo-Jo Hubbard, co-founder of Electron, which builds software for flexible power markets, automation will make a market that’s cheaper, more efficient and require less effort from consumers.

“We need to make sure that every single electric vehicle and heat pump is communicable with the grid and suppliers, which we’re not even doing right now,” she said. “This really is step one for a flexible, low-carbon grid.”

(By William Mathis, Todd Gillespie and Celia Bergin)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Geo

Ridiculous. Not even one mention of nuclear for reliable baseload. What a lot of leftist tripe!