US looks beyond tariffs to secure critical titanium supply

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters)

First there was steel. Then there was aluminum. Now titanium joins the list of metals found to be threatening the national security of the United States.

The U.S. Commerce Department launched a so-called Section 232 investigation into titanium sponge imports in March last year and submitted it to the White House in November.

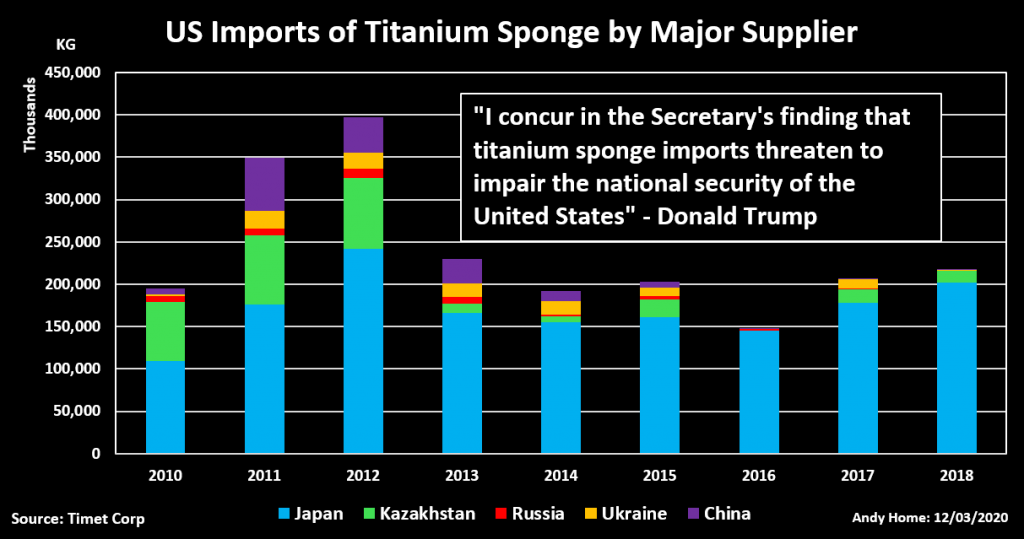

Commerce found that U.S. import dependency, amounting to 68% of the country’s consumption in 2018, threatens the viability of the last US producer of this intermediate form of a metal critical to both civilian and military aircraft manufacturers.

President Donald Trump agrees.

However, there will be no titanium tariffs to match those implemented on imports of both steel and aluminum in 2018.

Rather, there will be talks with Japan, the dominant supplier of sponge to the U.S. market.

The Secretary of Defense is tasked with taking “all appropriate action” to support “domestic production capacity for the production of titanium sponge to meet national defense requirements.” (Presidential Memorandum, Feb. 27, 2020).

The preference for cooperation over confrontation with importers is partly down to titanium’s unique supply chain. But it is also a sign that the Trump administration’s critical metals policy is evolving beyond simple tariffs.

Last US sponge plant may close

If TIMET Corp’s “aging production facility” closes, the “United States will be completely dependent on imports of titanium sponge and scrap, and will lack the surge capacity required to support defense and critical infrastructure needs in an extended national emergency,” according to the Department of Commerce.

TIMET, which is part of Precision Castparts, an industrial holding group owned by Berkshire Hathaway, is operating its Henderson plant in Nevada below capacity and needs to decide whether to invest in an upgrade of its chlorination plant.

The company “has made it abundantly clear that substituting low-priced imports for domestic titanium sponge may be the most reasonable choice if the economics of domestic titanium sponge production do not improve,” TIMET said in a May 22, 2019 submission to the Section 232 report.

Allegheny Technologies Inc. has already made its choice. In 2016 it closed the only other domestic U.S. sponge facility at Rowley in Utah in favour of using imported sponge to refine into metal.

Fragile supply chain

That tells you there is no shortage of titanium sponge in the world. Indeed, it is a market that has been struggling with excess production capacity for many years.

Nor is there any shortage of the raw material that starts the titanium production process. Global reserves of ilmenite and rutile are plentiful and one of the world’s largest producers, Rio Tinto Fer et Titane, is operating just over the Canadian border.

There is no obvious imminent threat to U.S. titanium supply, particularly given that the lion’s share of titanium sponge imports come from Japan rather than potentially hostile China, which dominates many other critical mineral supply chains.

It is clear from TIMET’s Section 232 “Rebuttal Comments” that both titanium metal product producers such as ATI and Arconic and end-users such as Boeing were against any punitive measures that would in their eyes artificially raise the price of a readily available input.

However, TIMET won the national security argument with the White House on the grounds that the sponge part of the titanium supply chain represents what the U.S Defense Department would classify as a potential “critical point of failure”.

It’s all very well having lots of raw material on your door-step but 90% of the world’s ilmenite gets diverted into the pigments industry.

Converting raw material into titanium sponge prior to refining and casting is a specialised business to the point that the United States Geological Survey cites only six sponge producing countries outside the States: China, Japan, Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and India.

China and Russia, the largest and third-largest producers respectively, are increasingly problematic suppliers for US defence contractors

China and Russia, the largest and third-largest producers respectively, are increasingly problematic suppliers for U.S. defence contractors, meaning U.S. imports in 2018 were sourced almost exclusively from Japan and Kazakhstan.

Sponge, moreover, is critical to many high-end titanium products. Although the titanium milling process generates lots of scrap that can be looped back into the production stream, many end-users specify a minimum input of primary material.

Stockpiling might be one option but sponge degrades over time, according to TIMET, which argues its unique role in the U.S. supply chain ticks nearly all the “risk archetypes” identified by the Defense Department.

Production versus price

The Trump administration agrees but seems to accept that tariffs would only damage an already struggling aviation manufacturing sector and upset a key political and economically.

How then to square the circle of preserving domestic production capacity without penalising Japanese imports?

The Secretary of Defense is now supposed to be actively working on supporting domestic production capacity.

A government-funded chlorination plant at Timet’s Henderson facility has already been suggested. ATI’s mothballed Rowley plant will also surely come under government review.

But low-priced imports work against such investment.

The Presidential Memorandum paves the way for talks with Japan on “measures to ensure access to titanium sponge in the United States”.

We don’t know what those talks will encompass. The full Commerce Report on titanium sponge hasn’t to date been made public.

However, TIMET’s submission to the report, which is publicly available, contains some intriguing possibilities.

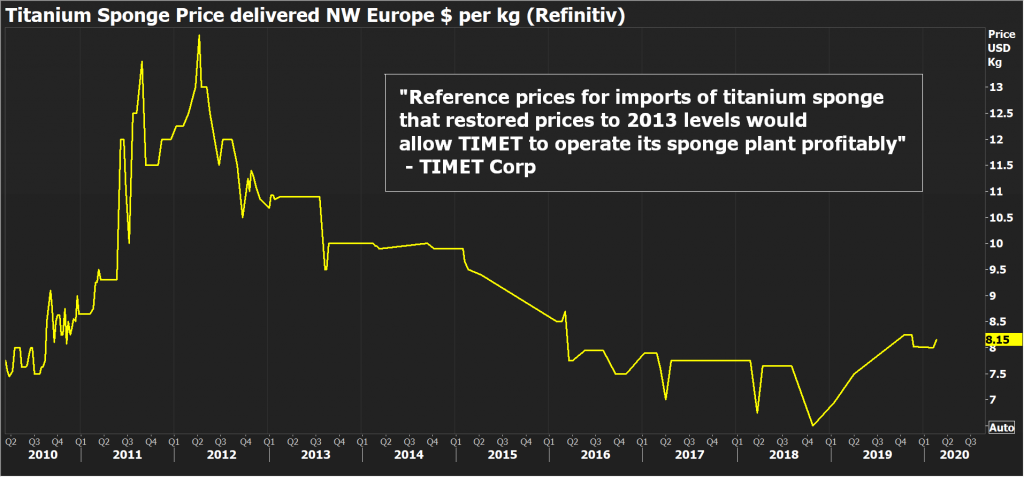

TIMET hasn’t been calling for punitive tariffs but rather “believes the best solution would be achieved by implementing bilateral agreements with titanium sponge producing nations establishing reference prices for titanium sponge.”

The target would be “reference prices (…) that restored titanium sponge prices to 2013 levels”, which would allow Henderson to keep operating and encourage Japanese producers to make required capital investments, according to TIMET.

It claims that end-users such as Boeing could easily absorb higher prices for a product that is often only a blending input in the titanium production process.

A bilateral agreement with Japan, which accounted for 94% of all US imports in 2018, might be structured as a win-win if it allowed for a mutually-acceptable increase in prices over time.

US consumers could argue this would amount to tariffs by the back door but this administration has already shown it believes national security trumps markets.

Titanium sponge will prove an interesting example of just how far it will go to secure its critical metals supplies.

(By Andy Home; Editing by David Evans)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments