Tycoon whose bet broke the nickel market walks away a billionaire

By 2:08 p.m. Shanghai time on March 8, it was clear that Xiang Guangda’s giant bet on a fall in nickel prices was going spectacularly wrong.

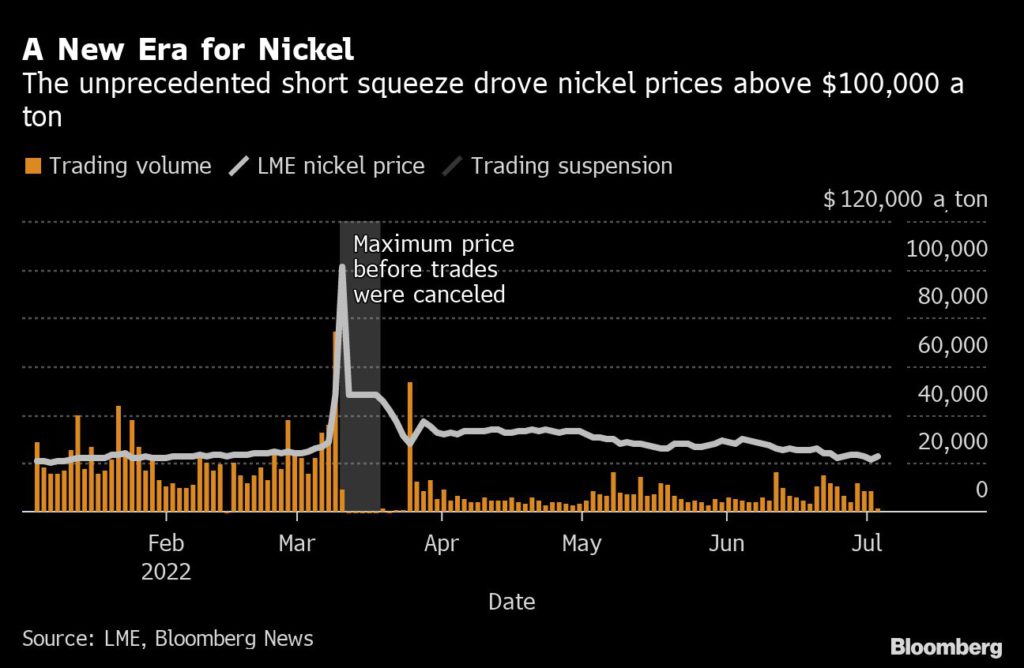

Futures had just skyrocketed above $100,000 a ton and his trade was more than $10 billion underwater. It was threatening not only to bankrupt Xiang’s company, but to trigger a Lehman Brothers-like shock through the entire metals industry and possibly topple the London Metal Exchange itself.

But Xiang was calm. Within hours, more than 50 bankers had arrived at his office wanting to hear how he planned to respond to the crisis. He told them simply: “I’m confident that we will overcome this.”

And he did.

Four months on, the nickel price is falling, as Xiang had predicted. The coterie of banks led by JPMorgan Chase & Co. that were baying for his blood has been repaid. He has closed out nearly all his short position in nickel, making a loss on the trade of about $1 billion — a manageable sum given the profits being generated elsewhere in his business empire, say people who know him.

Crucially: the man nicknamed ‘Big Shot’ in Chinese commodities circles is poised to walk away from the fiasco with his multibillion-dollar mining and steelmaking company, Tsingshan Holding Group Co., intact and even expanding.

But while Xiang moves on, others are left dealing with the destruction wrought by the crisis. His miraculous escape was thanks in no small part to the actions of the LME, which controversially intervened to prevent prices from rising and then suspended trading until Xiang had struck a deal with his banks.

Those on the other side of the trade, who lost billions, were furious. Months later, the LME is dealing with a raft of investigations and lawsuits, and the nickel market is still reeling.

Related: JPMorgan exits nickel saga as tycoon shrinks ‘big short’

“Nice to see that JPMorgan and The Big Shot got out of this whole thing with only scratches,” Cliff Asness, founder of AQR Capital Management, said last week in a tweet thick with sarcasm. “It’s just heart warming.”

This account of how Xiang extricated himself from a short squeeze that rocked the global metals markets is based on numerous interviews with people who were involved, all of whom requested anonymity. Multiple attempts to seek comment from Tsingshan were unsuccessful.

Massive short squeeze

Xiang had built up his massive short position in late 2021 and early 2022 partly as a hedge, partly as a bet that a planned jump in Tsingshan’s production this year would drag down prices. But when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine jolted global markets, nickel started climbing — gradually at first, before rocketing 250% in an epic squeeze.

On the evening of March 8, senior bankers crowded into a room at Tsingshan’s headquarters demanding answers. Others dialed in for video calls from London or Singapore. Of those present, some didn’t leave until early the next morning.

The crowd that night was so large because Xiang’s position was spread across about 10 banks and brokers — he had been a good client for many of them, including JPMorgan, for years. But after nickel started spiking on March 7, Tsingshan struggled to meet its margin calls. Now he owed each of them hundreds of millions of dollars.

The LME had eventually intervened to halt trading a couple of hours after nickel hit $100,000. It also canceled billions of dollars of transactions, bringing the price back to $48,078, where it closed the previous day, in what amounted to a lifeline for Xiang and Tsingshan.

To reopen the market, the LME proposed a solution: Xiang should strike a deal with holders of long positions to close out his trade. But a price of around $50,000 would be more than twice the level at which he had entered his short position, and would mean accepting billions of dollars in losses.

Xiang, who is in his early 60s, stood firm. From a start making frames for car doors and windows in Wenzhou, eastern China, he’d built Tsingshan into the world’s largest nickel and stainless steel producer, with an empire stretching from mines in remote Indonesian islands to steel mills on China’s east coast. Along the way, he’d acquired a reputation for visionary thinking and a taste for betting big.

He had caught the attention of the LME before, when in 2019 Tsingshan was on the other side of a short squeeze, withdrawing large amounts of nickel inventories from exchange warehouses and causing prices to jump.

This time, his aggressive approach to trading was having much wider ripple effects.

The spike in prices and the trading freeze caused havoc for companies that use nickel, like stainless steel mills and makers of batteries for electric vehicles. Some simply stopped taking new orders. On the LME, dealers were left frantically trying to recoup missed margin calls from clients who couldn’t pay, and at least one had to seek financial support from its parent company.

Yet with unprecedented chaos rippling through the industry, Xiang — still facing his bankers in the early hours of March 9 — had a key advantage. They were more terrified than he was.

If he refused to pay, they would have to chase him in courts in Indonesia and China. What’s more, he had executed his nickel trade through a variety of corporate entities – such as the Hong Kong branch of battery unit Ruipu Energy Co. – and it wasn’t clear the banks would even have the right to seize Tsingshan’s most valuable assets.

The bankers understood that if things went wrong, their careers would be over, one person who was in the room remembered.

JPMorgan, which had the biggest exposure, took the lead. The group included some international players like Standard Chartered Bank Plc and BNP Paribas SA, but many were Chinese and Singaporean banks that had little experience handling a situation like this.

Personal guarantee

Xiang told the assembled bankers he had no intention of closing the position anywhere near $50,000. A few hours later he was delivering the same message to Matthew Chamberlain, chief executive of the LME. Tsingshan was a strong company, he said, and it had the support of the Chinese government. There would be no backing down.

Instead, he wrote a list of the assets he was willing to put up as collateral: a string of ferronickel plants in Indonesia. But for some of the bankers, that wasn’t enough. They wouldn’t be able to do any due diligence on the Indonesian assets for weeks or months, and even those who worked closely with Tsingshan hadn’t seen the facilities for years because of the pandemic.

So Xiang made a further concession that was both valuable and, in Chinese business culture, humbling: a personal guarantee. If Tsingshan didn’t pay its debts, the bankers could turf him out of his home. That was what he was willing to offer. Take it or leave it.

It wasn’t much of a choice. On March 14, a week after the chaos that engulfed the nickel market, Tsingshan announced a deal with its banks under which they agreed not to pursue the company for the billions it owed for a period of time. In exchange, Xiang agreed a series of price levels at which he would reduce his nickel position once prices dropped below about $30,000.

When the market reopened two days later, prices moved lower, easing the strain on Xiang and the banks. A brief dip below $30,000 allowed Tsingshan to cover about 20% of its short position.

The pressure on the LME was only intensifying, however. The exchange’s regulators launched reviews of its governance and oversight. The Dallas Federal Reserve and International Monetary Fund joined in a chorus of public criticism, and many hedge funds were still furious at the LME’s decision to cancel trades.

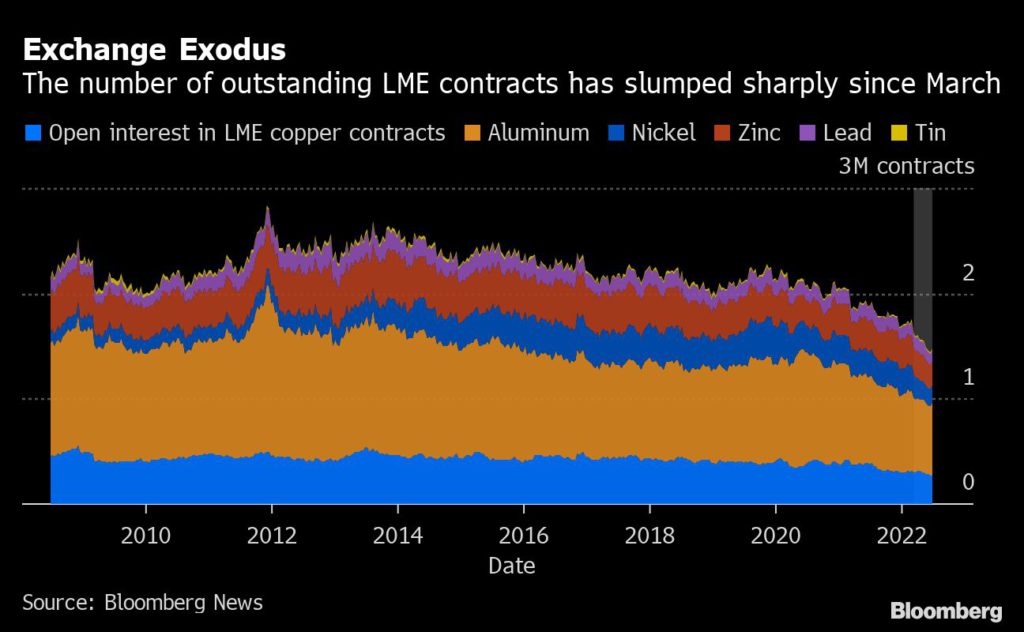

“The moment we realized what was really happening, we felt we could no longer entrust the LME with our clients’ money,” said Transtrend, a $6.7 billion Dutch algorithmic fund. Open interest across the exchange’s six main metals slid to the lowest in more than a decade as traders headed for the exit.

Each month, Tsingshan and its banks reviewed their standstill agreement. After the initial dip, nickel spent long stretches in limbo with prices hovering around $33,000.

It was a nervous time. Tsingshan still had a vast short position, meaning it and its banks could still be exposed to large losses if prices started rising again — for example, if sanctions against Russia led to an actual disruption in nickel supplies, which so far they hadn’t.

Finally, in May, prices tumbled decisively below the key $30,000 level after China’s lockdowns dented metals market sentiment. Over the following weeks, Tsingshan reduced its position — which in early March had been over 150,000 tons — to just 60,000 tons.

By this point, prices were below the level at which Tsingshan had stopped being able to pay its margin calls in early March, which meant Xiang no longer owed the banks any money. He proposed dropping the personal guarantee from the deal, seeing it as a humiliating concession to his earlier financial troubles. Some of the banks were willing to do so, but JPMorgan was not: the number of nickel plants used as collateral was reduced, but the personal guarantee would stay. A JPMorgan spokesman declined to comment.

It was not the only sign that the crisis had soured Xiang’s relationship with his banks. In June, as recessionary fears swept global markets, Xiang’s short position was beginning to look like a smart trade. He asked some of his banks for a little flexibility, allowing him to run the position for longer than had been envisaged under their deal. Again, JPMorgan said no, and by the end of June Xiang had exited his position entirely with JPMorgan and several other banks, leaving him with a remaining short of less than 20,000 tons.

People familiar with the matter estimate Tsingshan’s losses on the trade at around $1 billion. Xiang isn’t concerned. The loss has been roughly offset by the profits of his nickel operations over the same period. The standstill agreement, which Xiang extended from the initial three months, is set to expire in mid-July.

Now ‘Big Shot’ is moving on with his life, focusing on plans for the future at Tsingshan, which had revenues of $56 billion last year. His ability to trade on the LME may be reduced, for now at least, but he is still able to trade on the Shanghai Futures Exchange. He has ambitions to expand, not only in Asia, but also to Africa. And Tsingshan is as powerful as ever in the nickel market: a massive increase in production from his plants in Indonesia is one of the key factors driving prices lower, much as Xiang predicted.

But while Xiang may be moving on, the LME is still dealing with the fallout. Regulators have pointed to the chaos in nickel as a sign of the risks lurking in commodity markets, and called for greater oversight of the entire sector. Hedge fund Elliot Investment Management and trading firm Jane Street have launched legal action against the LME, seeking nearly $500 million.

And the nickel market is still broken, say people involved in it, with both open interest and trading volumes stuck at sharply lower levels as traders step away from using LME prices in their contracts. Jim Lennon, a veteran nickel market-watcher and managing director of Red Door Research Ltd., estimates that less than 25% of global nickel output is now being sold on the basis of LME prices, down from 50% before the crisis in March.

“A lot of the industry now has temporarily disengaged from the LME,” he says. “The market is still functioning, but it’s struggling.”

(By Alfred Cang, Jack Farchy and Mark Burton)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Balter

All’s fair in love and war. I bet the LME gets off with doing the right thing under the circumstances (I bet they show they followed instructions if the court dogs deep enough) I bet the court won’t for the same reason.