Turkish gold fever spurs dollar oddity unseen in Erdogan era

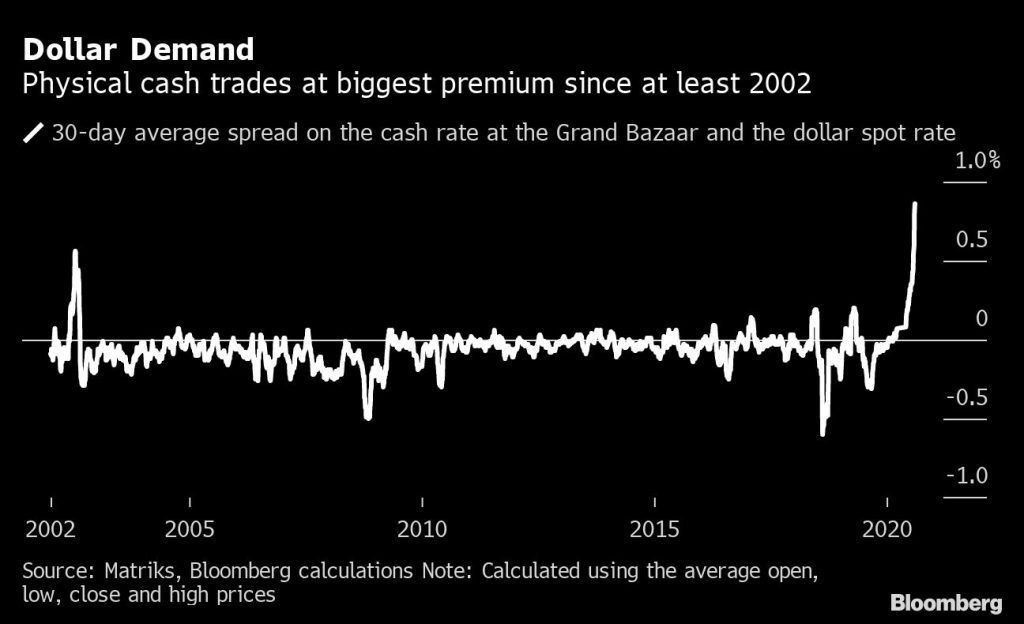

It took weeks of frenzied gold trading in Istanbul’s historic commercial center to spur one of the biggest gaps between the cost of physical dollar bills and the official exchange rate in 18 years.

Home to scores of foreign-exchange kiosks that double up as brokers for the precious metal, the Grand Bazaar is often seen as the benchmark for the country. Traders there also mostly use cash to settle gold dealings — and dollars were in short supply.

As a result, U.S. currency bills in this market have been trading at the biggest premium relative to the official exchange rate since at least 2002 over the past month, according to local data provider Matriks Bilgi Dagitim Hizmetleri and Bloomberg calculations. The difference has narrowed close to zero this week.

As the price of bullion soared to a record beyond $2,000 an ounce in August while the lira fell to an all-time low, traders at the world’s oldest covered market began bidding up the price of physical dollars to meet surging demand from clients for gold, a popular form of household savings.

“There has been a cash squeeze in the Grand Bazaar,” said Cumhur Tasdelen, a board member at Troy Precious Metals in Istanbul. “As demand for hard currency and gold jumped, this has created a cash squeeze, widening margins in kiosks.”

Over the past 30 days, dollar bills were on average 0.83% more expensive than the rate offered in the wholesale global currency market.

Fever subsides

With the gold prices now showing signs of easing, and authorities in Turkey moving to tighten policy to steady the currency, the dislocation looks to be subsiding. The precious metal suffered its biggest three-day loss since March this week, helping the spread between the two dollar rates narrow to just 0.3%.

Still, the last time it blew out to a level anywhere near as wide was during a political deadlock in 2002 that forced the coalition government at the time to call early elections. The vote proved to be a seismic event that wiped out Turkey’s ruling political class, and ushered in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s AK Party, which has remained in power ever since.

This time, however, it was less politics than the strain on the economy from the coronavirus pandemic and outflows of foreign capital that helped warp the exchange rates.

As the lira weakened, local households and businesses took to hoarding dollars to hedge against bouts of inflation and currency deprecation that have eroded their savings over the decades. In July, Turkish households and companies purchased $11.7 billion of foreign-currency, driving their dollar and euro deposits to a record $213 billion, equivalent to more than a quarter of the Turkish economy.

Savers’ hedge

Others prefer to hold dollar bills at home. That’s because they can avoid a 1% tax the government collects on foreign-currency purchases executed through banks.

The levy was imposed in May 2019, as part of a series of measures designed slow the currency’s depreciation.

A currency dealer in Istanbul’s Atasehir region, who declined to give his name because of the sensitive nature of the subject, pointed to the low yield on dollar accounts that further reduces the appeal of storing foreign exchange at banks.

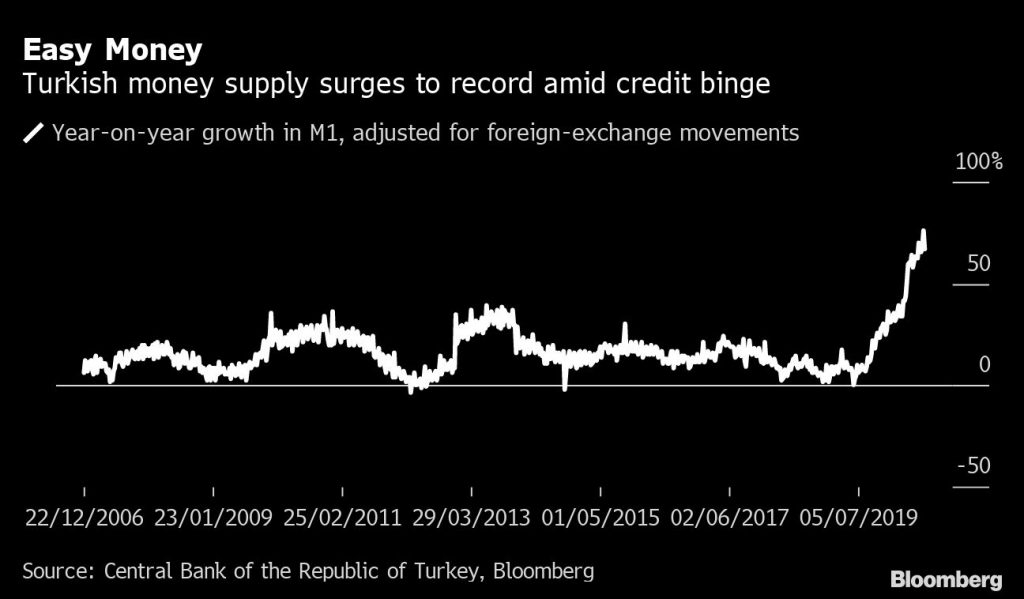

A steep monetary easing cycle and a government-sponsored credit push have also done their part to heighten distrust of their currency among Turks.

Growth in money supply, as measured by currency in circulation and bank deposits, is running at an annual rate close to 70% when adjusted for foreign-exchange movements, a record high, according to central bank data going back to late 2006.

Holding liras, meanwhile, is guaranteed to sap savings in real terms because the average one-month deposit account in the local currency yields an annual 6.87%, while headline inflation is just under 12%.

Facing pressure on the currency to weaken but reluctant to raise rates, authorities have instead started curbing the supply of credit. On Thursday, the central bank announced the latest measures that would effectively raise the cost of funding.

The question now is whether the shift in monetary policy is enough to persuade Turks to move out of gold and dollars and back into owning their local currency. The lira weakened for a third day on Friday, and was trading 0.5% weaker at 7.3785 per dollar as of 2:25 p.m. in Istanbul.

“In the last couple of days we’ve seen a correction — we have to watch how far this will go on,” Tasdelen at Istanbul’s Troy Precious Metals said, referring to the pullback in the price of gold. “But some investors see this as an opportunity to buy.”

(By Constantine Courcoulas, Cagan Koc and Asli Kandemir, with assistance from Kerim Karakaya)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments