Traders are already gaming the new Russian metal sanctions

It took less than a day after the UK and US banned future sales of Russian aluminum, copper and nickel on the London Metal Exchange before traders had zeroed in on a way to make money off the convoluted new rules.

The opportunity lies in massive piles of Russian metal already sitting in the exchange’s global warehouse network. And the LME might not like what they’ve got planned.

The bottom line of the sanctions is simple: no Russian material produced after April 12 may be delivered onto the LME. The idea is that the restriction will drive down demand and prices for Russian supplies, but its miners can still sell to non-US and -UK buyers outside of the LME, where the vast majority of the global trade in metals happens anyway. Prices initially spiked on the news, but quickly fell back in a sign that markets aren’t expecting major disruptions.

Now, as the dust settles, the growing buzz in the metals world is how the new rules, combined with a series of quirks in the LME’s contract structure and global warehouse system, have thrown up an opportunity for a complex but lucrative trade. Multiple traders and brokers have described the play in conversations this week, while LME chief executive officer Matthew Chamberlain fielded questions about it in a call with market participants on Sunday.

For the metals world, it’s the latest episode in a rich history of traders seeking to exploit loopholes to profit from giant stocks of aluminum on the LME, which can generate hundreds of millions of dollars a year in storage and handling fees.

The sanctions, and the way that the LME has decided to implement them, have created a new multi-tiered market of metal categories, with varying restrictions attached to each. While the exchange can no longer accept delivery of “new” Russian supplies, the UK has actually relaxed earlier rules to allow UK buyers to accept Russian metal that was already in the LME system when the rules were announced.

This category of metal — the LME calls it “Type 1” — is what many in the market are now focusing on.

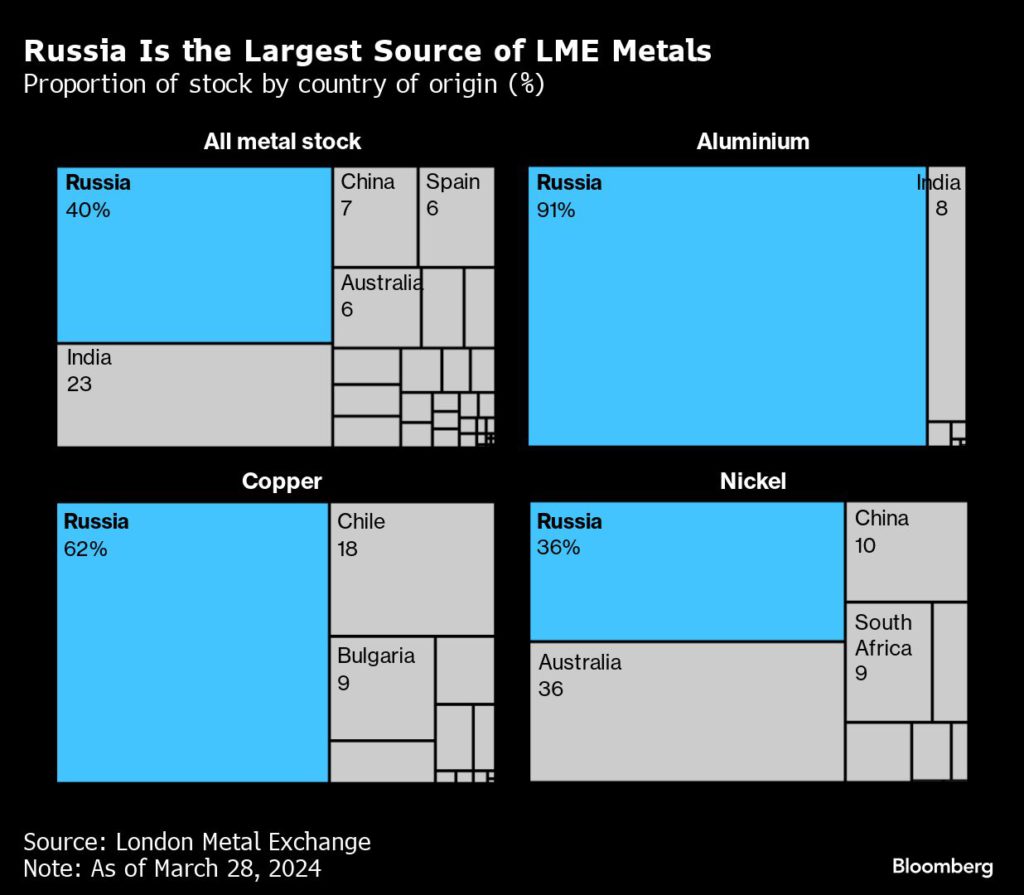

The growing percentage of Russian stocks in LME warehouses has been a controversial subject since the invasion of Ukraine, and the share had increased further in recent months — to more than 90% for aluminum — after UK buyers were blocked in December from taking delivery of Russian metal, making the supplies even less attractive for everyone else.

But UK nationals and companies are only allowed to accept Russian supplies that were already in the the LME system before April 13 — the permission doesn’t extend to any metal registered after that date, or “Type 2.”

Crucially: once Type 1 metal leaves the system, it loses its special status. If it’s re-registered, it becomes categorized as Type 2, and faces the same restrictions. (At its discretion, the LME will allow traders to withdraw cargoes and move them to different warehouses while preserving the Type 1 status, but only in narrow circumstances)

So, here’s the play:

First, traders are rushing to withdraw the large volumes of (Type 1) Russian metal already stored on the LME.

Then, after selling it (now, as Type 2) back on to the LME, they can cut a deal with the warehouse to share the rent from future owners. For warehouses, the rent share deals are a way to incentivize traders to deliver to their facilities, rather than a competitor’s.

The trade is complicated, but the idea is a simple one: they’re ultimately betting that the metal could sit there for months on end if UK nationals can’t withdraw it, and many western industrial consumers don’t want it. Previously the metal might have been attractive to buyers in China, but in the coming months that market is likely to be stuffed with newly produced Russian metal.

And for every day the metal sits there, the trader receives a sliver of the warehouse’s profit on it.

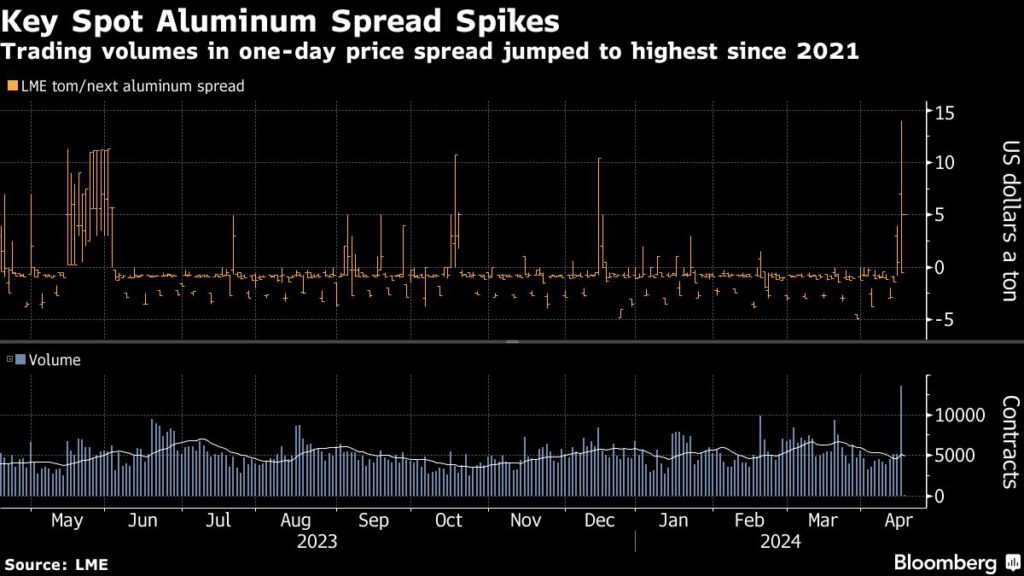

Potential evidence that traders are mobilizing can be seen in a sharp rise in the prices that they’re paying to obtain spot metal. Aluminum contracts expiring in one day reached a $14 premium to those maturing a day later on Tuesday, in a condition known as backwardation that signals buyers are rushing to secure spot supplies. The spread was trading at a discount before the measures were announced, and it was the busiest day of trading in the spread since June 2021.

The spread between April and May contracts also closed in a large backwardation on Monday. Several people involved in the LME aluminum market who asked not to be identified said that the sharp moves in the spreads reflected traders looking to secure tonnages for these so-called rent-share deals.

On Tuesday, nearly $200 million worth of aluminum was ordered for withdrawal from LME warehouses, signaling that the trade is now well underway. Another $16 million was requested on Wednesday.

While the deals could be lucrative for the traders if they’re right that no one will want to touch the metal, they could prove problematic for the LME. Since the invasion of Ukraine, it’s faced criticism that it risked becoming a dumping ground for Russian aluminum, but it’s avoided blocking Russian deliveries unilaterally on the grounds that consumers have still been showing an appetite for the increasingly large volumes of Russian stock that have been delivered on to the exchange.

In implementing the new UK sanctions, the exchange said it will be monitoring inflows and outflows to assess whether that remains the case — and traders appear to be making a bet that it won’t.

“The LME continues to monitor the market closely and remains ready to take further action should that be required, including in relation to adverse market behaviours as a result of the introduction of the recent sanctions,” a spokesperson for the exchange said in response to questions.

Whack-a-mole

Rent-share deals have become popular on the LME in recent years, particularly as the exchange introduced whack-a-mole regulations to clamp down on other lucrative and sometimes controversial ploys that traders have come up with to make money from its global warehousing network.

Most famously, during the financial crisis banks including Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. and traders like Glencore Plc bought up huge volumes of surplus aluminum and stashed it in warehouses they owned. As demand started to recover, consumers reacted with fury as they realized it would take years to get hold of the mountains of metal the banks and traders were sitting on.

While loose supply conditions persisted in the aluminum market, another popular trade was to withdraw metal from the LME and store it much more cheaply elsewhere, capturing a spread between depressed spot prices and higher-priced futures. Typically traders held the metal in off-exchange warehouses — or private sections of LME sheds — but sometimes they even stashed it in fields.

(By Mark Burton, Archie Hunter and Jack Farchy)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments