Trader known as ‘big shot’ battles mystery nickel stockpiler

In Chinese commodity circles, he’s known as “big shot” — the man who controls the world’s largest nickel producer and isn’t afraid to place big derivatives bets on where prices are headed next.

Now Xiang Guangda has emerged at the center of a market drama that’s fueling some of the largest price swings in years for a key ingredient in the fight against climate change.

On one side is Xiang and several of his Chinese peers, who’ve amassed short positions in nickel derivatives to hedge their production against the risk of falling prices, according to people familiar with the matter. On the other is an unidentified nickel stockpiler who controlled at least half of the inventories on the London Metal Exchange as of Feb. 9.

As speculation swirls about the mystery stockpiler’s identity, Xiang finds himself in an unusual position: on the losing side of a trade.

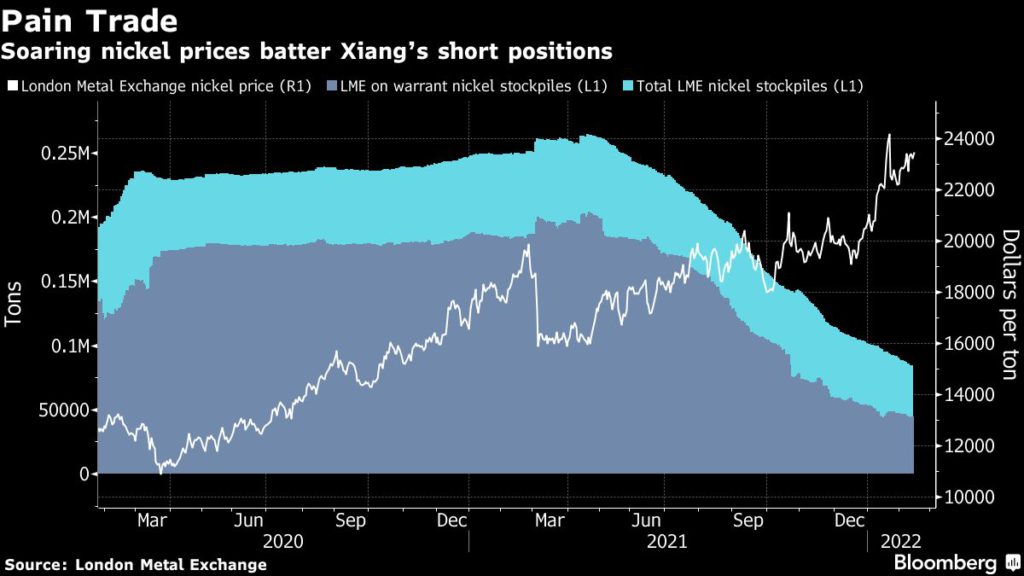

Nickel has surged more than 25% over the past year, touching the highest level in a decade last month. Demand is booming for the metal in electric-car batteries, while market indicators suggest supplies are tight. Inventories on the LME have tumbled to the lowest level since 2019 and the metal’s spot price has reached the highest premium ever to the three-month futures contract.

“There’s a bit of a squeeze on the LME,” said Jim Lennon, a senior commodities consultant at Macquarie Securities in London.

The episode highlights the outsized role of a handful of players in the market for nickel, whose scarcity Elon Musk has identified as one of the biggest hurdles to ramping up production of EV batteries. Xiang has been a key figure in some of the metal’s biggest swings in recent years, helping drive prices sharply higher by snapping up inventories in 2019 and triggering a brief tumble in early 2021 after unveiling a cheaper way to produce supplies for batteries.

It’s unclear how much of a risk the nickel rally poses to Xiang’s closely held Tsingshan Holding Group Co., but the company’s short position could offset some of its earnings from producing the metal if the gains persist. Tsingshan didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

The company, founded by Xiang and his wife He Xiuqin, got its big break in the late 1980s with a business making frames for car doors and windows in China’s eastern city of Wenzhou. It went on to pioneer the large-scale use of nickel pig iron, a semi-refined product and low-cost alternative to the pure metal, to make stainless steel.

Tsingshan jolted the market last year by saying it planned to make battery-grade nickel using an alternative process, refining it up from materials previously reserved only for stainless steel.

The company is currently running three nickel matte production lines with capacity of about 3,000 tons a month. It aims to increase that capacity to 100,000 tons per year by October 2022. If it succeeds, Tsingshan would solve one of the biggest bottlenecks for electric battery production — and potentially put downward pressure on nickel prices.

The company started building the short position last year in part because Xiang wanted to hedge rising production and believed the surge in nickel prices would fade, according to one person familiar with his thinking. The cost of Tsingshan’s production in Indonesia is lower than $10,000 a ton, compared with a benchmark price of over $23,000 on the LME.

For now, though, there’s little sign that market prices are poised to fall. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. predicted last month that nickel demand will outstrip supply by 30,000 tons this year, up from an earlier estimate of 13,000 tons.

The unidentified stockpiler held somewhere between 50% and 80% of nickel warehouse warrants monitored by the LME, according to daily data from the exchange. The warrants entitle traders to LME metal, and the exchange reports the concentration of holdings in bands rather than as precise figures.

The position has been maintained for almost a month, a relatively long period of time that suggests the stockpiler is either very bullish or could need the metal for its own future supply contracts. “I think part of what’s going on is that there’s been a bit of a mad panic to stockpile material, because of the rapidly growing market for batteries,” Lennon said.

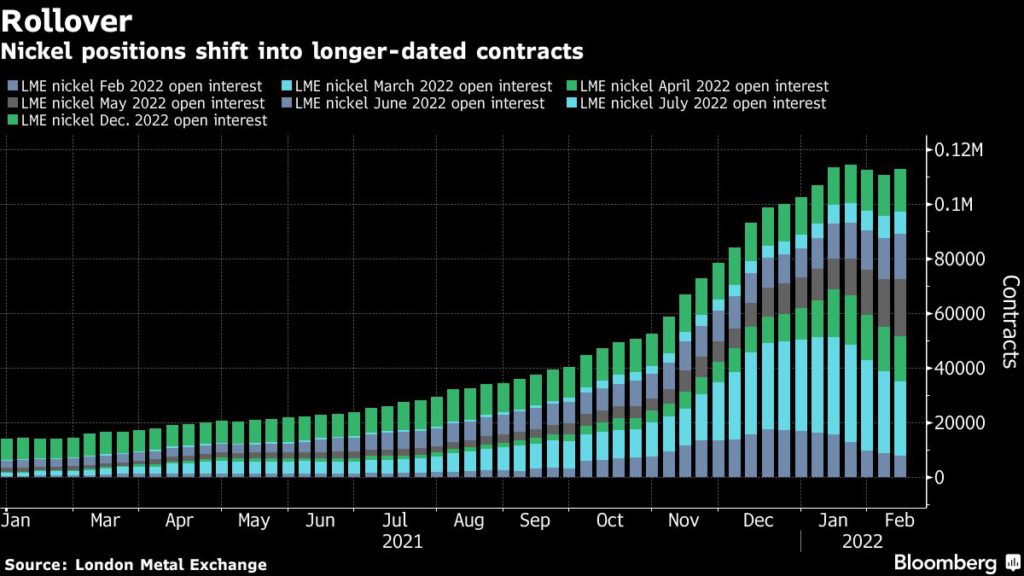

The big question is whether Xiang will continue to battle it out with bulls or unwind his short position. One complication for the Chinese tycoon: because his production doesn’t match the grade of nickel used in settlement on the LME, the contracts aren’t a perfect hedge. That means they could become a cash drain if he’s forced to stump up more margin or roll over his positions.

There’s some circumstantial evidence that Xiang isn’t ready to give up. Open interest in LME contracts expiring in March has in recent weeks begun shifting to longer-dated contracts. While it’s hard to know for sure what’s behind the move, it could be a sign that Xiang and other short sellers are digging in for the long haul.

(By Alfred Cang, with assistance from Mark Burton, Martin Ritchie, Jack Farchy and Tom Redmond)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments