Trade spat, virus add fuel to China’s push for iron ore security

A souring relationship with Australia and iron ore supply shocks in Brazil may reignite China’s ambitions to reduce its dependence on major overseas producers for the material critical to its giant steel industry.

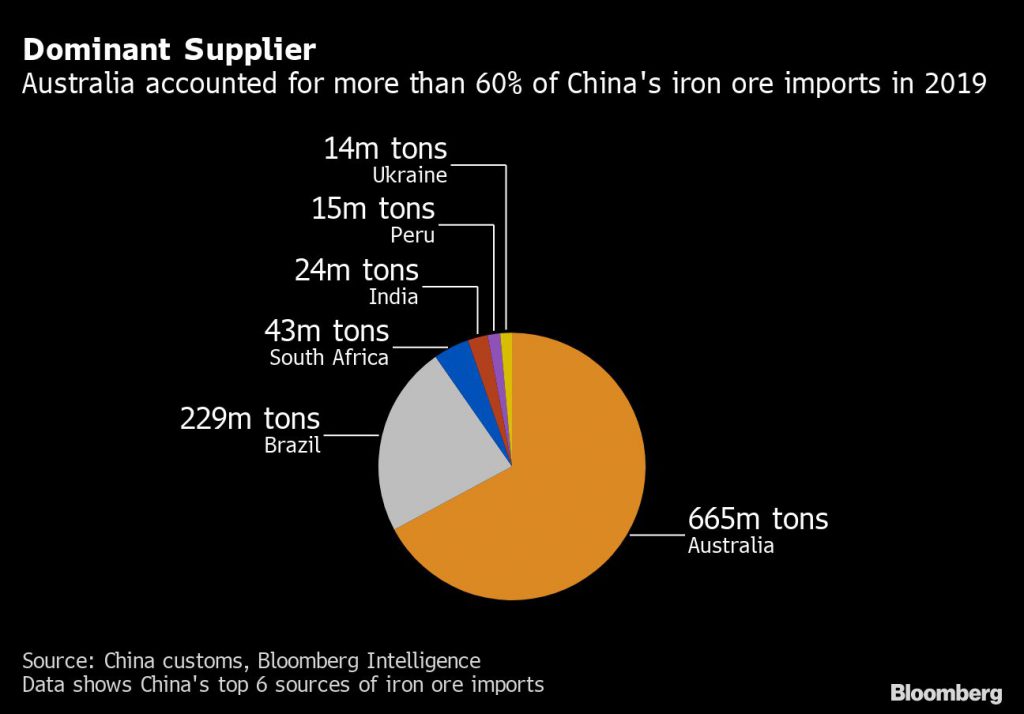

China has long sought to diversify its sources of iron ore — more than 60% of imports come from Australia and about 20% comes from Brazil — to rein in supply risks and price volatility. That drive is back in the spotlight after disruptions to Vale SA operations sent prices surging, less than 18 months after a dam disaster roiled the market, and a diplomatic row between China and Australia prompted speculation that iron ore could be targeted in the spat.

“China definitely needs to accelerate investment in overseas iron ore mine assets from a long-term perspective. It can also reduce the price volatility caused by short-term gaps between supply and demand by securing a stable source,” Ban Peng, an analyst at Maike Futures Co. said by phone. “However, it will take years from investing to full production.”

China has long sought to diversify its sources of iron ore — more than 60% of imports come from Australia and about 20% comes from Brazil

The China Iron & Steel Association’s secretary general He Wenbo last month called on mills to jointly develop large iron ore projects overseas or buy stakes in mining companies abroad, Caixin reported, citing a discussion proposal to the nation’s parliamentary meeting in Beijing.

The National Development and Reform Commission has said China should boost domestic output and support communication with global suppliers around more reasonable pricing mechanisms.

Trade spat

Tensions between China and Australia have escalated after the latter’s call for an independent probe into the origins of the coronavirus incurred Beijing’s wrath. Commodities have emerged as a flash point, with China imposing anti-dumping duties on Australian barley, suspending meat imports from four facilities and considering targeting more products.

The Global Times, a tabloid run by the flagship newspaper of the Communist Party, said in June that Australian iron ore could be targeted, although such a move wouldn’t be the first option given it would have a negative impact on China’s economy. It could seek supplies from domestic mines or from Brazil and Africa, according to the paper, which doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of the party’s leadership.

Long-term goal

China has pledged to diversify iron ore sourcing for decades and companies already invest in overseas operations, including Sinosteel Corp.’s Channar mine joint venture with Rio Tinto Group in Australia and Shougang Group Co.’s Marcona project in Peru.

Getting assets to production can take time. State-owned Citic Ltd.’s Sino Iron project in Australia began shipping ore about four years later than planned and continues to face challenges to long-term financial sustainability.

“In the long term, it is possible to displace some Australian iron ore,” said Rohan Kendall, principal analyst for iron ore and steel costs at Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “But large undeveloped iron ore deposits tend to be located in higher-risk, less-developed and higher-cost countries. China will not want to replace Australian iron ore, rather it would like to create additional competition in the market.”

The country’s ambition is not necessarily to reduce its reliance on imports, but on purchases from foreign companies, according to Kendall.

A current focus is in Guinea, where some of China’s biggest state-owned firms are close to getting the go-ahead to develop Simandou, the world’s largest untapped iron ore deposit. The project is divided into four blocks, with blocks 1 and 2 controlled by a consortium backed by Chinese and Singaporean companies, while Rio Tinto Group and Aluminum Corp. of China own blocks 3 and 4. Caixin reported China Baowu Steel Group Corp. and other steelmakers are currently seeking to acquire Chinalco’s shares.

Local options

As well as looking abroad, China wants to boost domestic output, though any increase is likely to take a long time and would need elevated prices to ensure profitability. Tax incentives could be an option to attract miners, according to Tracy Liao, commodities strategist at Citigroup Inc.

Benchmark spot iron ore is up 8% this year to about $99 a ton. That’s spurred domestic producers to ramp up, but mines will shut once prices fall to $70 or lower, said Woodmac’s Kendall. Major miners in Australia can produce a ton of iron ore for less than $15.

Chinese operations also face headwinds from environmental regulation and resource depletion, according to Maike Futures’ Ban.

Increasing scrap use has been floated as another option that would reduce iron ore consumption. China’s steel mills mainly use blast furnaces, which limits the amount of scrap used to about 20% of inputs, although there are opportunities for a shift in the longer term.

“Beyond 10 years, rising scrap availability in China will shift the cost dynamics between iron ore and steel scrap,” incentivizing producers to boost steel scrap use, said Citigroup’s Liao.

Still, China is unlikely to be able to break its dependence on Australian iron ore any time soon. Australia accounted for 64% of the Asian nation’s purchases in the first five months of this year, up from 62% a year earlier, while Brazil lost market share.

“In the short term, it is impossible to replace Australian iron ore,” said WoodMac’s Kendall. “It’s a symbiotic relationship between the two countries — any trade disruption would cause iron ore shortages for China’s steel industry and mean that Australian iron ore has nowhere to go, damaging the economies of both countries.”

(By Annie Lee and Krystal Chia)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments