Three times the gold price collapsed – and lessons for today

The causes have always included some combination of economic miracle, respite from grave fiat money disorder most of all in the US hegemon, anti-gold regulations, and global detente.

Prudent analysts should never ignore these potential factors, even when the gold price seems to have embarked on a new journey to the summits as has most likely been the case since winter 2015 and 2016.

The gold price had sunk at that time to almost $1,000 per ounce from its multiple peaks in 2011–12 ($1,900 in summer 2011). That collapse reflected primarily the non-emergence of high inflation in the US despite the vast “money printing” and long-term rate manipulation under the first Obama administration.

Scared investors who had feared runaway inflation had not reckoned with the strong downward influence on prices (of goods and services) from globalization and digitalization.

Nor had they fully digested the extent to which monetary radicalism had held back business spending in the US and other advanced economies given widespread concerns that another bubble-bust cycle was under way.

In looking at the gold price beyond the next summit we should be concerned about restrictions which could imperil the free market in gold

Fanning the gold price collapse of 2013–15 was continuous chatter from the Fed about normalization ahead. The oil and wider commodity market slump from late 2014 slotted into the growing narrative of no imminent goods and inflation danger.

Normalization never came. The Yellen Fed aborted all rate rises planned for 2016 in response to the growth cycle downturn and passing global asset market setback. The ECB and BoJ embarked on monetary radicalism even starker than in the US. Briefly in 2018, excitement in the media that Fed Chief Powell, convinced big business tax cuts meant boom ahead, was at last bringing monetary “accommodation” to an end, triggered a faltering of the incipient gold price recovery. Events this year have re-fuelled gold’s rising trend from its end-2015 trough.

Meanwhile news of continued “low inflation” does not impress many gold holders who worry about colossal budget deficits in the US and likely waning downward influences on prices from globalization and digitalization. Vast accumulated mal-investment and the weakness of the invisible hand in the context of unsound money — and strengthened monopoly capitalism — does not encourage optimism for economic miracles. This optimism was a key element in the epic gold price collapse from January 1980 to end 2002.

In terms of 2018 dollars, the gold price fell from $2,010 to $480 over those twenty-two years. In fact, there were two sub-collapses.

The first was the plunge to $750 (2018 dollars) in 1984. This reflected Paul Volcker’s monetarist assault on “the greatest peacetime inflation” coupled with an extraordinarily high level of real US interest rates. The height was in line with widespread speculation on the miracle of “Reaganomics.” The devaluation of the dollar at Plaza (autumn 1985) and beyond accompanied by the Volcker/Greenspan monetary inflation of 1985–88 as directed by top White House official James Baker led to a brief spring for gold.

Then the disintegration of the Soviet Empire followed by the emergence of US economic miracle (the IT boom of 1995–99) helped bring a second collapse, with 10-year real interest rates (as quoted in the 10-year US TIPS market) rising above 4 percent.

Aggressive monetary ease from 2003–04 (the Greenspan/Bernanke Fed breathing in inflation because it had fallen “too low”) as an accompaniment to the Bush administration’s dollar devaluation policy ahead of the November 2004 election set gold on its second journey to the summits (from 2003 to 2011–12). The first such journey had been from 1968 when the US ceased intervening in the free market to hold down the price of gold at $35 per ounce.

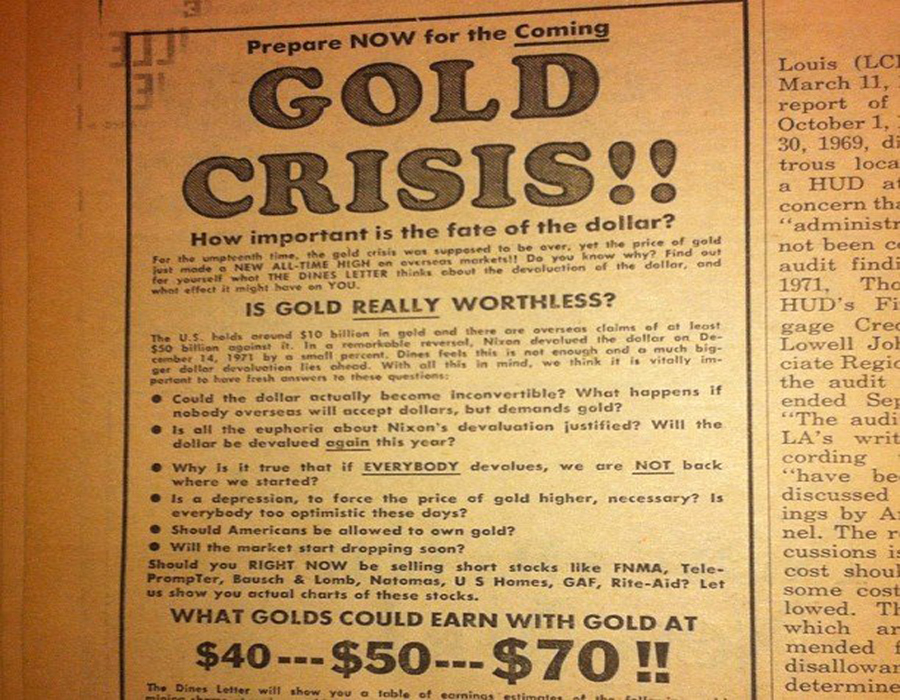

The free market was then (mid-1960s) just returning to life, having long been choked by regulation — starting with Roosevelt’s criminalization of private gold holdings within the US (1934) and then widespread exchange controls throughout the globe.

The dismantling of these accelerated from the late 1960s (US gold ban lifted in December 1974, European and Japanese exchange controls abolished through 1970s).

These restrictions had doubtless played a role in the long collapse of the gold price from 1934 to 1968 (during which time the gold price in 2018 US purchasing power had fallen from $650 to $250 per ounce). Economic miracles also played an important role.

The mid-1950s to the mid-1960s were years of great economic miracles, not just the famed ones in Japan and Germany, but also in the US. Accordingly, rates of return to capital were extraordinarily high, dampening the appeal of gold. Even real interest rates were substantially positive, albeit held well below the level which would have been in line with the miracles.

Central bankers led by the Martin Fed sought to hold nominal rates down employing Depression Era-regulations on credit and deposit interest rates for that purpose. Rapid productivity growth camouflaged underlying conditions of monetary inflation from showing up in goods and services markets.

The widely told story about how the gold link of the dollar under Bretton Woods acted as bulwark against monetary inflation is myth. As soon as private gold markets came back to life, the anchor role snapped (March 1968).

The remaining three years during which the official gold window remained open prolonged the opportunity for European governments to obtain the yellow metal from the US Treasury at the bargain prices still available.

In looking at the gold price beyond the next summit we should be concerned about restrictions which could imperil the free market in gold.

There is virtually no scope for banks or other financial institutions to develop “bullion banking”

The lone serious non-fiat money is still in fragile condition due to government restraints. There is virtually no scope for banks or other financial institutions to develop “bullion banking” in which gold deposits could be used as a medium of payment (where clearing between the institutions would take place at a central gold “depot”) whether nationally or internationally.

Regulators defend their veto here in terms of the wider war against cash — highlighting concerns that gold hoards include a criminal element whose money-laundering operations could flourish in bullion banks.

The Bundesbanker’s advice that outlawing large denomination notes due to their use by criminals is akin to banning Mercedes-Benz autos because the mafia like driving them does not go down well with the regulators. The gold bulls might be right that gold is safe against new regulation so long as the Republicans hold the White House.

The likelihood is not trivial, however, that Washington will eventually join in imposing new regulations on gold trading and international shipments, perhaps in time for the next price collapse, albeit from a new record high summit.

Brendan Brown is senior fellow (non-resident) Hudson Institute. As an international monetary and financial economist, consultant, and author, his roles have included Head of Economic Research at Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group. He is also an Associated Scholar of the Mises Institute. His latest book is The Case Against 2 Per Cent Inflation (Palgrave, 2018) and he is publisher of “Monetary Scenarios,” Euro Crash: How Asset Price Inflation Destroys the Wealth of Nations and The Global Curse of the Federal Reserve: Manifesto for a Second Monetarist Revolution.

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments