This 36-year-old is leading Latin America to a green revolution

At 36, Gabriel Boric is Chile’s youngest ever president and the most left-wing in half a century. He also aspires to be one of the world’s greenest heads of state.

Boric is in the vanguard of a new awareness across Latin America of climate change and its link to inequality, whether through access to clean water, the rainforest’s destruction, indigenous rights or sharing the benefits from mining.

In Colombia, Gustavo Petro is the frontrunner for the presidency on a ticket of environmentalism. Honduras President Xiomara Castro is moving to curb mining six weeks after taking office. And in Brazil, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva sounds serious about tackling the burning of the Amazon as he bids to unseat Jair Bolsonaro later this year.

“Climate change, dear compatriots, is not an invention,” Boric said in his acceptance speech on election night back in December.

“We cannot look the other way when our farmers and peasants, when entire localities are deprived of water or when unique ecosystems are destroyed.”

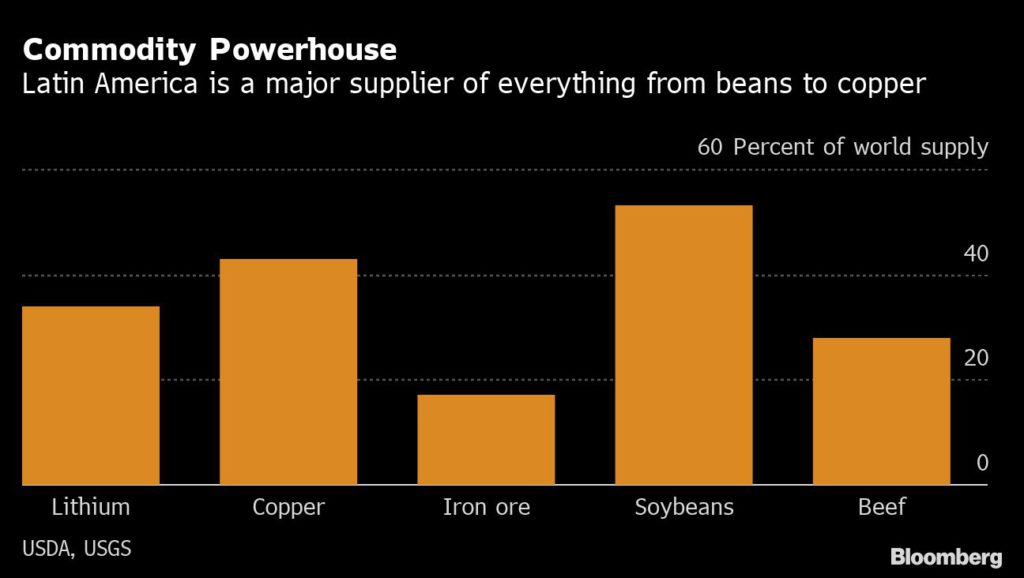

For Boric among others, the goal is to transition to a new development model that’s less reliant on just exporting natural resources. That’s potentially a hard sell at a time when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is exposing just how vital Latin America’s output is for the world — and as governments enjoy the revenue from record commodity prices. Regardless, if it gains traction, the movement promises far-reaching implications for a resource-rich region that produces much of the world’s food as well as the building blocks of the global economy.

“Is it a concern? Yes and no,” said Nolan Peterson, chief executive officer of World Copper Ltd., a Canadian company that has the Escalones and Cristal exploration projects in Chile. Sudden changes in government policy can complicate life for established companies, yet Peterson sees it as a new reality that the industry just has to deal with. “It’s not just governments that are pushing back on this, it’s investors that are actually wanting more stringent requirements in permits,” he said.

Politically, the rise of a climate-conscious agenda is coalescing with a swing to the left across the region that is reminiscent of the early years of the 21st century. But this time, rather than a repeat of the so-called pink tide, Latin America looks to be on the cusp of a green wave.

Take Colombia, a major exporter of oil, gas and coal, where Petro says the terms left- and right-wing are obsolete. For him, the new fault line is between the climate-friendly “politics of life” and the kind of economic models that perpetuate fossil-fuel extraction supported by what he calls the “politics of death.”

A 61-year-old senator who has a commanding lead in the polls for May’s election, Petro argues that the fight against climate change needn’t jeopardize efforts to combat poverty. If elected, he envisions “a grand coalition of powers” with other leaders to “transition Latin America toward economies that are decarbonized, productive and based on knowledge,” he said in an interview in January.

Many remain skeptical it can work. Without a doubt, concern for the environment “is becoming more mainstream,” says Sergio Guzman, director of Colombia Risk Analysis in Bogota. Still, for Petro “it’s going to be very difficult to realize his vision from a political, legal and practical economic angle.”

Colombia gets two-thirds of its energy from hydropower, but oil and gas account for nearly a third of all its exports. As president, Petro would have significant sway over state-owned oil company Ecopetrol SA, which controls exploration in the Andean nation. But canceling future drilling contracts would be bound to face a court challenge, and higher fuel prices would have an outsized negative effect on the poor, a pillar of Petro’s base, said Guzman.

A generation ago, a block of like-minded governments led by the late socialist Venezuelan leader, Hugo Chavez, promised to use their natural resources to bring an end to inequality. But revenues were mismanaged, corruption ran rampant, and poverty soared as soon as a commodity supercycle crashed. The environment didn’t get much of a look in.

Now, though, the region is drying out and burning up like never before, and pressure is growing at home and abroad to set ambitious climate goals as a prerequisite for tackling poverty. The result is a new wave of climate action.

“The forces of the left on the continent, the most progressive politicians, are taking an important step compared to what we saw in the past in incorporating the environmental agenda due to climate change,” said Marcio Santilli, a founder of the Socio-Environmental Institute in Sao Paulo.

In Honduras, the new government has announced plans to stop issuing permits for open-pit mining, describing “extractive exploitation” as “harmful to the state.” In Peru, President Pedro Castillo was elected last year on a platform that included supporting local communities in their battles against mining companies.

Even where governments are not making noticeable climate efforts, there is evidence of public pressure forcing their hands. In Argentina, the government had to defend oil exploration after thousands protested against its decision to grant concessions in the deep waters of the southern Atlantic.

In Ecuador, meanwhile, the Constitutional Court ruled at the end of January that a local referendum sought by environmentalists on mining within the metropolitan limits of Quito may go ahead. President Guillermo Lasso, elected last year as Ecuador’s first center-right leader in nearly two decades, has in any case shown himself to be an enthusiastic backer of climate action. He attended the UN COP26 summit and in January expanded a marine protection area around the Galapagos Islands.

There are still notable holdouts. Mexico’s Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who sees energy independence as a matter of national pride, is looking to significantly boost oil output and is building a $12.5 billion refinery. In Argentina, energy subsidies that encourage consumption cost the government $11 billion last year. Peru’s Castillo has by no means shied away from mining, the bedrock of the economy.

The most important bellwether will be Brazil, the region’s biggest economy and an agricultural superpower, as it heads into presidential elections in October. Bolsonaro, the incumbent, has drawn the scorn of US President Joe Biden and threats from major financial institutions to divest assets unless he changes course on climate action.

Cumulatively over time, Brazil is the fourth biggest source of greenhouse gases worldwide, and the top producer of carbon dioxide as a result of fires and the change of land use from farms to pastures. Yet Bolsonaro, an unabashed backer of agribusiness, has gutted protection agencies, failed to enforce fines and overseen the largest destruction of the Amazon in over a decade.

As Lula, his main rival, looks to win a third term in a nation mired in recession and double-digit inflation, the economy is clearly the main voter concern. What’s more, his environmental track record is mixed: Deforestation rates were halved under Lula and his environmental minister, Marina Silva. But he also opened up thousands of miles of seabed to oil drilling, and a flagship mega-dam project flattened swaths of rainforest, upending indigenous communities. He’s already talking about offering voters fuel subsidies.

But Lula, 76, is sending signals of his intention to defend the Amazon from ranchers and farmers in a break from Bolsonaro’s policies. “What we need to do is convince society that a standing forest could be more profitable to Brazil’s development than cutting down forests,” he said in October. Last month, he appointed a senator to run his election campaign who comes from the same party as Silva.

Brazil will have to demonstrate a commitment to reducing emissions if it wants to return to the world stage and unlock international funding, according to Ilona Szabo, president of the Igarape Institute, a think-tank in Rio de Janeiro.

“Inconsistencies will not be allowed any more,” she said.

In Chile, Boric is promising one of the biggest shake-ups since the 1970s. He plans to tighten climate targets; help wean industry off fossil fuels; and overhaul the nation’s water management model following years of drought. All that while facing a split congress and an economic hangover from the pandemic.

Another challenge lies in an independent process to draft a new constitution that could lead to even more radical reforms than Boric is proposing, threatening tax revenue needed to fund social spending.

“I wouldn’t say we’re not concerned about the new government in Chile,” said Kent Masters, chief executive officer of Albemarle Corp., the world’s largest lithium producer, citing its environmental focus. “There’s definitely risk, but we think the new government will be responsible around the industry and the economy.”

If Boric and his climate scientist environment minister, Maisa Rojas, can succeed in striking that balance, other leaders will follow, said Oliver Stuenkel, a professor of international relations at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in Sao Paulo.

“If he does a good job, he will inspire others,” Stuenkel said. “He will become the trailblazer.”

(By Andrew Rosati and James Attwood, with assistance from Ezra Fieser, Marisa Wanzeller, Oscar Medina, Yvonne Yue Li, Michael McDonald and Amy Stillman)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments