There’s a way to quit coal without wrecking jobs and communities

It’s a persistent global conundrum: Can policymakers close coal mines and power plants without ruining local economies in the process?

In August, a delegation of Vietnamese officials looking to answer that question took the two-hour drive east from Melbourne into the Latrobe Valley. Bundled against the Australian winter, they sped past the cooling towers of the Yallourn power station and the open-cut mines near Morwell, vestiges of the region’s rapidly dying industry. The 18 members of parliament visited a new battery facility built on the site of a now-defunct coal-fired power station, and met with local leaders to discuss their approach.

After almost a century as Victoria’s central provider of electricity — some 90% comes from Latrobe and the broader Gippsland area — most of its mines and power stations are scheduled to close between 2028 and 2035, if they haven’t already. Yet the area has kept decline and diseases of despair at bay, with plans for solar farms, battery storage and the country’s first offshore wind installations. Unemployment is low and the population — currently about 300,000 — is growing, along with household income. Real estate values are rising.

“There is a confidence, in the community, that we’re going to be okay,” said Chris Buckingham, head of the Latrobe Valley Authority, a regional agency created in 2016 to help manage the coming energy transition. “This is not a smiling-while-drowning conversation, right? This is about, if we get this right, if we work together in a harmonious way, we’re far more likely to come out ahead.”

Coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel, still generates about a third of the world’s electricity. It’s especially common in emerging economies, which need fast, cheap, reliable energy and often argue that they shouldn’t have to jeopardize their development to solve a problem that, historically, they didn’t create. Renewable energy has made huge strides, but problems run deeper in countries with constrained infrastructure, and there’s no easy solution: Already-rich countries have yet to deliver the billions promised to fund a transition, and the economic blight triggered by the closure of mines and power plants in the US, UK and Europe is hardly inspirational.

Still, pressures to quit coal are accelerating. All parties to the Paris Agreement have to submit an emission-cutting plan to the United Nations, and foreign funding for coal has largely dried up. The 2021 COP climate talks in Glasgow introduced aid packages to help developing nations speed the closure of coal plants.

Last year, Vietnam signed one of the world’s largest climate finance deals worth $15.5 billion, designed to encourage an orderly coal phase-out that also protects its economy. By its own timeline, it has about 25 years to burn the fuel — and to plan for its peaceful demise.

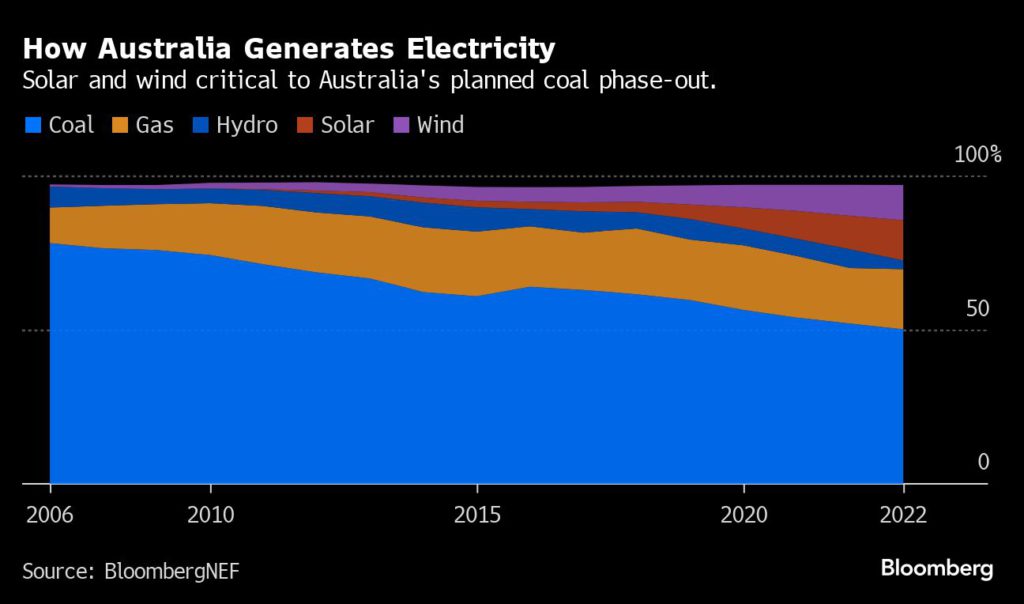

The idea of slowly, deliberately phasing out coal is relatively new. It hinges on cooperation from the fossil fuel industry and compromise from climate activists. The opportunity to learn from earlier, chaotic mine closures elsewhere is, ironically, a byproduct of Australia’s historically late arrival to climate action. The country is still highly reliant on coal — more so than Vietnam, by some measures — but the Latrobe Valley transition is critical to its new net-zero ambitions.

Emerging economies have less money to spend and a wide range of competing priorities — including growth, which depends on more power, not less. But the broad challenges are similar enough, said Thang Do, a climate policy researcher at Australian National University who organized the study tour for the Vietnamese lawmakers.

“People are worried: ‘If we shut down coal, what will the alternatives be? And how about the workers in the mines and the plants, and their families?’” he said. “You cannot just close the coal power next year or even in the next five years. But planning — that is something policymakers could do.”

The pain of past economic upheavals remains sharp in the Latrobe Valley. People are still talking about the thousands of jobs destroyed with the privatization of the state electricity commission in the 1990s. Then there was the abrupt closure of the Hazelwood mine and power station in 2017, three years after the devastating fire that spewed smoke for six weeks and caused damage upwards of A$100 million ($66 million at today’s exchange rates).

Even before that, Tony Wolfe had started advocating for a shift to renewables. He was 15 years old when he started as an apprentice electrician at Hazelwood; he wrapped his career 44 years later at AGL Energy Ltd.’s Loy Yang B. By the midpoint, though, he said, “I could see the writing on the wall. I was working at a power station for 29 years that was designed with a 35-year life span. We hadn’t even talked about planning for another one.”

Wendy Farmer, whose husband worked at Hazelwood and volunteered for the local fire brigade, came to a similar realization. In the wake of the fire, she grew furious at the failure of government and industry — and her neighbors — to acknowledge the harms caused by coal.

“If your baby can’t breathe at night because of the pollution in the air, you get it. It becomes personal,” said Farmer. She started a group called Voices of the Valley. Initially focused on demanding accountability for the fire, they were soon calling for a total overhaul of the area’s economy.

“We would say, ‘We need to transition, we need to improve our health,’” she recalled. “And they would say, ‘We’ve got coal ’til 2048, we don’t need to transition.’”

Voices of the Valley developed its own proposal for the region, then began to lobby the Victoria government. When the state established the LVA and announced A$266 million in funding for the region, Energy Minister Lily D’Ambrosio tweeted, “We heard you @wendyfarmer_.”

One of the LVA’s first tasks was to support the laid-off Hazelwood workers, almost all of whom ended up either with early retirement packages, placements in another local facility, or roles in the long process of decommissioning the mine.

It also became a champion for a slew of local projects, including a new performing arts center and a A$57 million geothermally heated aquatic center. The spending demonstrated investment, not abandonment, and softened community attitudes toward an agency that ultimately represented economic upheaval.

The LVA also began to develop relationships with renewable energy developers like Macquarie-backed Corio Generation, and Elanora Offshore, a five-member consortium that includes CLP’s EnergyAustralia and Royal Boskalis Westminster NV. There are now more dozens of large projects underway in Gippsland, worth about $55 billion in planned capital expenditure.

In general, these don’t require as many workers as coal mines and plants. But demand will be high for at least 15 years, estimates Charles Rattray, chief executive officer of Star of the South, a Victoria-based company that applied for one of the off-shore wind concessions.

“You have thousands of construction jobs” to build the projects, he said. “And there’s ancillary work in catering, accommodation, transport, the local supply chain.”

The LVA’s 2022 transition roadmap reflects more than 2,000 community meetings, Buckingham points out, and the work of a 48-person steering committee. “A successful transition for us is built from the ground up,” he said.

When Australia’s Labor Party won its first majority in nine years in 2022, it set out to reverse the previous administration’s entrenched denial of climate change and to shore up weakened ties with Southeast Asia. The clean energy transition is now listed as a “ pressing priority” of Australia’s $1.24 billion regional development aid. The country has committed $105 million to support sustainable economic growth in Vietnam.

The government also sponsored the Vietnamese delegation’s tour. Australia’s climate policies are far from ground-breaking, but it’s ahead of its regional neighbors.

“There’s high demand for learning from Australia’s experience,” said Thang, the academic. The Vietnamese wanted to know about the practicalities, policy instruments and technology, he said.

They spent a week in lectures at the Australian National University in Canberra and a week on site visits, including to the Latrobe Valley. The Vietnamese government declined Bloomberg Green’s requests for comment. Buckingham said their session was so animated they worked through the lunch break. “They were absolutely staggered by the age of our plants,” he said.

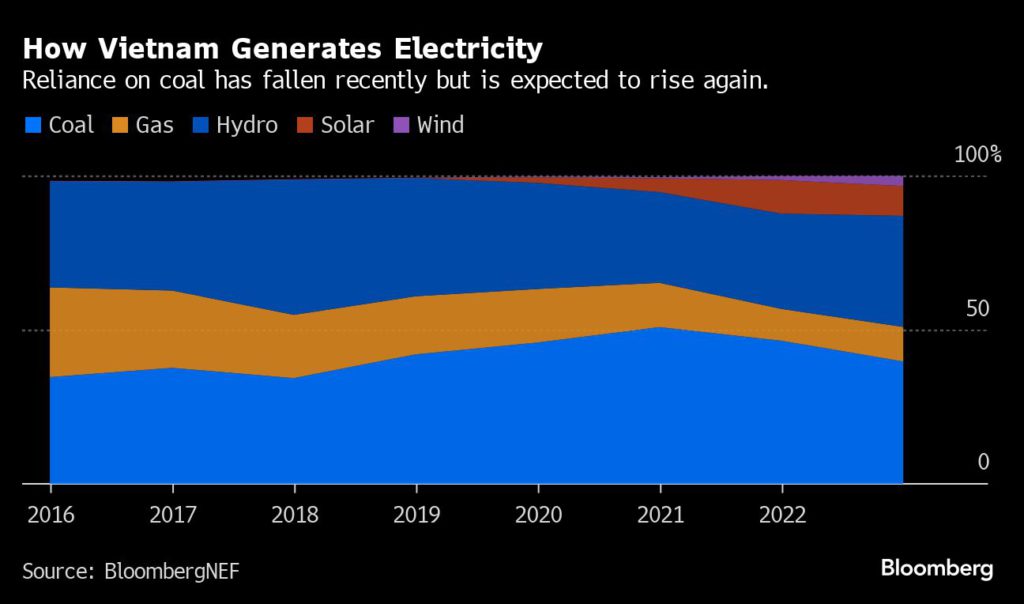

Coal is Vietnam’s single largest source of electricity and will continue to grow, the government says. At least six plants are set to come online by the end of the decade as the middle class expands and companies set up factories there.

That means it’s too early to think about taking coal plants off line or planning for the roughly 200,000 jobs at risk, said John Rockhold, chairman of the power and energy working group for the Vietnam Business Forum. At the same time, the country has set a 2050 net-zero goal. The country has already become a refuge for solar panel manufacturers eager to avoid the US tariffs on Chinese equipment.

“The government’s policy is: Let’s get our own renewable industry up and running,” Rockhold said. “We have the rare earths, we have the capabilities. Maybe we should slow down and build our own.”

This kind of long-term planning isn’t the most radical idea, but until recently, the coal industry — and its powerful allies — successfully argued there was no need, that climate change was overblown and its causes indeterminate. Net-zero commitments, with their timelines and interim benchmarks, force a longer view. They can also help shift the narrative from disappearing jobs to the new roles being created, as US President Joe Biden did in promoting the Inflation Reduction Act, a stimulus bill plowing billions of dollars into green technologies.

“You can’t just stand there and say, ‘Shut power stations,’” said Farmer, who after years of unpaid activism started in 2021 working as a community organizer for Friends of the Earth. “You just can’t take things away from people without offering solutions.”

For now, that means letting coal fires burn longer than the market — or the planet — can really tolerate. Rather than suffer another hasty closure, Australia has struck agreements to keep Gippsland’s remaining power stations open. Vietnam plans to experiment with so-called clean coal practices, which marginally reduce CO2 emissions. Among other trade-offs, those kinds of policies can distort the market for clean energy, discouraging investment just when it’s most needed.

In return, communities get a chance to survive the upheaval, maybe even to thrive. “People are rightly very proud of having provided electricity for Victoria for the last 100 years,” Wolfe said. “I think we’ve known for some time that what we’ve been doing is not great, that there’s better, cleaner ways to do it.”

“We have an opportunity to build an entirely new workforce, and that’s what I’m excited about.”

(By Janet Paskin)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments