The world’s most feared investor heads for showdown over nickel

A decade ago, Paul Singer did battle with the government of Argentina — and won. Next week, the notoriously pugnacious hedge fund boss is taking on a bastion of the City of London, the 146-year-old London Metal Exchange.

For Singer, the case is personal, say several people familiar with the matter. When on March 8 last year the LME decided to cancel billions of dollars in nickel trades as prices skyrocketed, Singer was appalled and affronted, seeing it as a perversion of the free market with few precedents in the modern history of finance.

Within a day, his fund Elliott Investment Management had hired lawyers to pursue action against the exchange.

Now, Singer’s fight is heading for a climax, as lawyers for Elliott and trading firm Jane Street take to the High Court in London to argue their case against the LME in a three-day hearing starting Tuesday.

Elliott is better known for its battles over sovereign debt, like the case against Argentina that included seizing one of the country’s warships, and for its activist investing – taking stakes in companies and agitating for change. Its aggressive tactics are the stuff of Wall Street lore. But Elliott is also a sizable player in commodity markets, two of the people said, trading across energy, metals and agriculture as well as more obscure markets like carbon credits.

In the run-up to the nickel crisis on the LME, an Elliott commodities portfolio manager called Tom Houlbrook had built up a bullish position in the metal, the people said. Houlbrook has worked at Elliott for 17 years, according to his LinkedIn profile. Elliott declined to comment, and the hedge fund hasn’t publicly disclosed all the details of its nickel position.

However, it had amassed a sizable position in call options in nickel ahead of the March crisis, according to legal filings and people familiar with the matter, meaning it stood to profit if prices spiked.

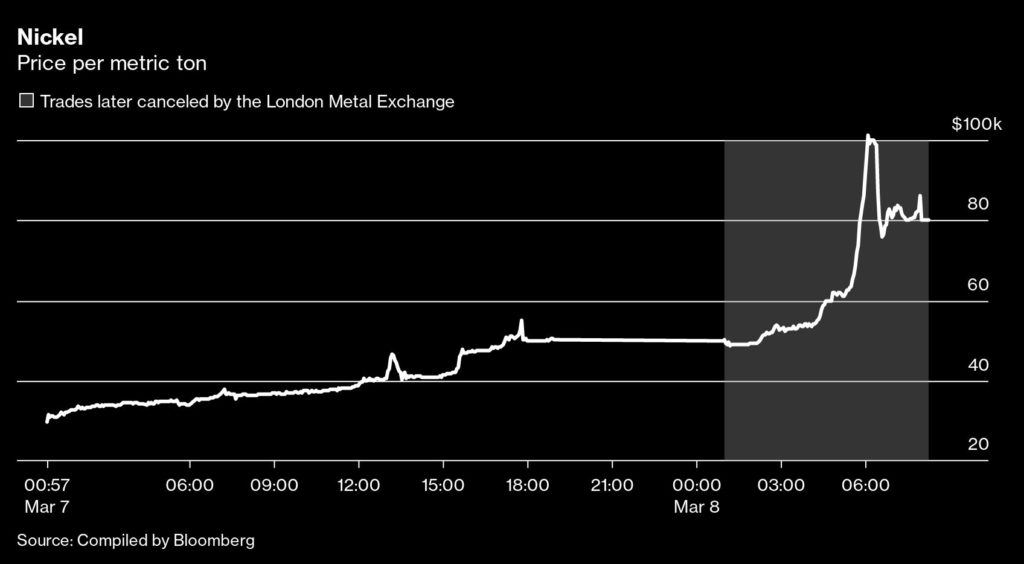

Which they did. Nickel surged in the early days of March, hitting a record on March 7 amid fears that Russian supplies could be shut off and a building short squeeze focused on Chinese tycoon Xiang Guangda and his company Tsingshan Holding Group Co.

In the early hours of March 8, prices more than doubled in a few hours. And by then, Elliott was selling. Over the course of the night, Elliott sold 9,660 tons of nickel for a total of $728 million — an average price of just over $75,000 a ton that effectively locked in what was set to be a sizable profit on its bullish bet.

But any sense of satisfaction only lasted a few hours. At 8:15 a.m. London time, the LME suspended the market. Just after noon, it retrospectively canceled all trades that had taken place that day.

Singer was incensed. His fellow billionaire hedge fund founder, Citadel’s Ken Griffin, described it as “one of the worst days in my professional career in terms of watching the behavior of an exchange” — a view that Singer shares, according to the people.

In the aftermath of March 8, Elliott’s lawyers engaged in a testy back-and-forth with the LME. At one point, it wrote to the LME jointly with AQR Capital Management – whose co-founder Cliff Asness has been one of the exchange’s most vocal critics – according to a filing.

But while Elliott proceeded to formally challenge the LME’s decision through a judicial review, AQR did not (although it has since filed a separate claim against the LME that could benefit if Elliott’s action is successful). That has left Elliott’s $456 million case as the standard bearer for the hedge fund industry in its battle with LME. Jane Street, with a much smaller claim of $15 million, was the only other party to mount such a legal challenge against the LME’s decision before a three-month deadline.

The LME itself is still wading through the fallout of the crisis. Beyond the legal challenges, it is also facing a rare probe from the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority over its handling of the debacle, while the nickel market itself has yet to return to normal.

Still, Elliott’s case — the first time it has pursued a judicial review — is likely to be an uphill struggle, say legal experts. Judicial reviews exist in the UK to review the decision-making of public bodies, a category that applies to the LME because it performs a regulatory role in the metals markets. But they focus on the way in which a decision has been made, rather than on its outcome.

Elliott and Jane Street will attempt to establish that the LME’s decision-making on the morning of March 8 was unfair, irrational, or motivated by improper motives. It’s an approach that has had some success before – United Co. Rusal International PJSC successfully persuaded a judge in 2014 that the LME hadn’t considered all viable alternatives when it changed its warehouse rules, although the decision was later overturned on appeal.

Circuit breaker

While criticism of the LME has focused on the decision to cancel billions of dollars of trades, the exchange made several other controversial decisions during the crisis.

The market was left open even after the LME’s clearinghouse stopped making intraday margin calls and several members failed to pay margin calls on time on March 7, the LME has previously disclosed. On March 8, the LME’s operations staff in Asia suspended the use of its “price bands,” a form of circuit breaker designed to limit extreme moves – a decision that may have exacerbated the price spike.

Based on its earlier filings, Elliott is likely to argue that the LME rejected alternative courses of action that would have had a less damaging outcome for the market than its decisions on March 7 and 8.

The LME will argue that its rulebook gives it broad powers to intervene to maintain market order, and that making it liable for Elliott’s losses could threaten the viability for all exchanges which perform a similar regulatory function, according to a person familiar with its thinking.

Still, Singer is used to fighting battles few others think he can win. It took him 15 years to secure more than $2 billion in payment from Argentina. Now, he’s determined to see the dispute with the LME through to the end, according to one of the people. Even if he loses next week’s case, he may be able to appeal the decision — and his past record suggests he’s unlikely to give up until every possible angle of attack has been explored. As he once told Bloomberg News: “If you don’t defend your rights, what do you have?”

(By Jack Farchy, Mark Burton and Jonathan Browning)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments