The promise and risks of deep-sea mining

The International Seabed Authority is working to set regulations for deep-sea mining as companies engaged in the clean energy transition clamor for more minerals. That transition will be a central focus at the United Nations’ COP28 climate summit in Dubai from Nov. 30 to Dec. 12.

The most-prominent of the three proposed types of deep-sea mining involves using a giant robot that is sent down to the ocean floor from a support vessel.

This robot travels to depths of roughly 5,000 meters to the ocean floor — the least explored place on the planet.

The seafloor, especially in parts of the Pacific Ocean, is covered by potato-shaped rocks known as polymetallic nodules that are filled with metals used to make lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles.

Many scientists say it’s unclear whether and to what extent removing these nodules could damage the ocean’s ecosystem. Automaker BMW, tech giant Google and even Rio Tinto, the world’s second-largest mining company, have called for a temporary ban on the practice.

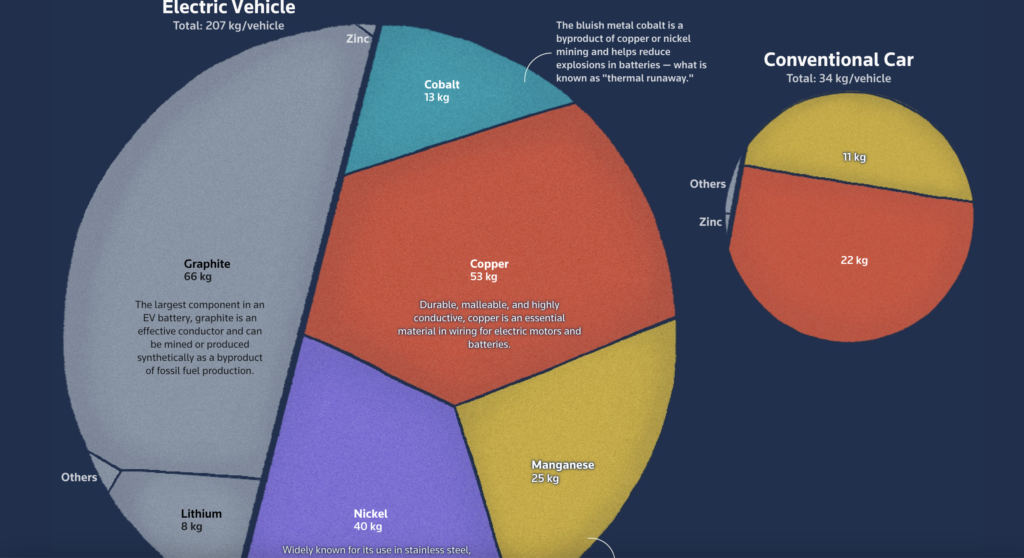

Composed of manganese, nickel, copper, cobalt and other trace minerals, these nodules hold some of the key ingredients needed to fuel the energy transition.

The metals in those nodules can be used to build electric vehicle (EV) batteries, cell phones, solar panels and other electronic devices. They are separate from rare earths, a group of 17 metals also used in EVs.

With climate change escalating, governments are under pressure to rein in emissions – especially from the transportation sector, which was responsible for about 20% of global emissions in 2022.

By 2040, the world will need to use twice the amount of these metals as it is using today in order to meet global energy transition targets, according to the International Energy Agency. And the world will need at least four times today’s amount in reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.

Many of the minerals that go into making an EV are becoming harder to find on land, pushing up mining costs in recent years. That’s increased prices for EVs and other electronics after they had fallen for years up to 2020. A typical EV needs six times more minerals in total than a vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine.

The scarcity and rising demand has made some governments and companies eager to allow mining in the oceans, which cover more than 70% of the planet’s surface.

First discovered by British sailors in 1873, the potato-shaped polymetallic nodules take millions of years to form as minerals in the seawater precipitate onto pieces of sand, shell fragments or other small materials.

Minerals are also found near deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where they’re called vent sulfides, and within seamounts known as ferromanganese crusts. Processes for extracting these minerals are similar to land-based mining, but harder to do underwater. That’s partly why the nodules are so appealing.

Land vs sea?

The mining industry has long had a mixed reputation on land. While it supplies the materials used to build our modern lives, it has contributed to deforestation, produced large amounts of toxic waste and in some parts of the world has fueled a rise in child labor. In 2019, a tailings dam — a structure that stores the muddy waste byproduct of the mining process — collapsed and killed hundreds of people at an iron ore mine in Brazil.

The average grade of mines on land — that is, the percentage of minerals extracted with every metric ton of rock — has declined over the last decade, requiring miners to dig deeper to extract the same amount of minerals.

All of these factors make deep-sea mining more appealing, supporters say. Environmentalists, however, say it’s a false dichotomy, as land mining will continue whether or not deep-sea mining is allowed.

Any country can allow deep-sea mining in its territorial waters, and Norway, Japan and the Cook Islands are close to allowing it. The International Seabed Authority (ISA), which is backed by the United Nations, governs the practice in international waters. The ISA missed a July 2023 deadline for setting standards for acceptable sediment disturbance, noise and other factors from deep-sea mining – a bureaucratic misstep that now allows anyone to apply for a commercial mining permit while the ISA continues negotiations.

“What are the alternatives if we don’t go to the ocean for these metals? The only alternative is more land mining and more pushing into sensitive ecosystems, including rainforests,” said Gerard Barron, CEO of Vancouver-based The Metals Co, the most-vocal deep-sea mining company and one of 31 companies to which the ISA has granted permits to explore for – but not yet commercially produce – deep-sea minerals.

Other companies with exploration permits include Russia’s JSC Yuzhmorgeologiya, Blue Minerals Jamaica, China Minmetals, and Kiribati’s Marawa Research and Exploration. Their potential future activities are seen as augmenting mining on land.

Where are these minerals?

The Metals Co — which is backed by metals giant Glencore — plans to use the robot to vacuum polymetallic nodules off a vast plain of the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ).

The company wants the ISA to set deep-sea mining standards, but said it reserves the right to apply for a commercial permit after July 2024 if the regulatory process stalls again. The ISA has said its work may not finish before 2025.

Companies need ISA members to sponsor them before they can apply for exploration or commercial permits. The island nation of Nauru, which is slowly being engulfed by the Pacific Ocean and sees deep-sea mining as key to the world’s energy transition, has sponsored The Metals Co.

Slowing the pace of climate change will be key for climate-vulnerable countries like Nauru if they hope to have a chance of adapting.

“Our existence is being threatened by the global climate crisis,” said Margo Deiye, Nauru’s ambassador to the United Nations and ISA. “We don’t have the luxury of time. This is quite a new nascent industry. Having clear guidelines in place, including standards, would be really helpful.”

Data from the U.S. Geological Survey and others show that the CCZ – which covers roughly 1.3% of the world’s ocean floor – contains more nickel, cobalt and manganese than all on-land deposits, a staggering volume that supporters say shows the practice should move forward. For copper, the CCZ’s deposits are roughly equal with those on land.

Multiple companies have been collecting small numbers of nodules as part of their robot tests in the Abyssal Zone, the part of the ocean below 2,000 meters. One such study is being conducted during November. If the ISA grants The Metals Co a commercial permit, the nodules will be sent to a refinery in Japan where the metals will be processed. The company says it will sell all parts of the nodules and thus there will be no waste byproduct beyond extraneous sand.

The Indian Ocean and parts of the Pacific Ocean are also rich in mineral deposits.

A March 2023 study conducted by the metals consultancy Benchmark Mineral Intelligence found that The Metals Co’s plans for the CCZ would cut mining emissions by at least 70%. The study focused on seven criteria, including contributions to ozone depletion and global warming. The study did find that on-land cobalt mining used less water, however. “We’re not talking about mining all of the ocean,” said Barron of The Metals Co, which funded the Benchmark study but said it had no control over its results. “We’re talking about one little patch.”

Deposits of nodules, crusts, and vent sulfides can be found globally, but only a fraction of these areas are being explored and are considered areas of economic interest.

The ISA has granted 19 exploration contracts for nodules, seven for vent sulfides and five for crusts. The Metals Co holds one; others are held by governments or state-controlled companies in China, Russia, France, India, Poland and Japan.

Decades of research has shown that deep sea mining could harm marine life or ecosystems. For example, sediment plumes kicked up by the robotic vacuum could disrupt animal migrations, according to one study published in February in Nature Ocean Sustainability.

The full importance of the nodules within the ocean ecosystem is unclear, and nodule regrowth could take millions of years. The nodules provide homes for anemones, barnacles, corals and other life forms, while bacteria and other invertebrates thrive on the ocean floor.

“These nodules are essential ecosystem architects. If you remove the nodules, you will remove the architecture supporting the entire oceanic ecosystem,” said Beth Orcutt, an oceanographer at Maine’s Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences who participated in the ISA standards debate.

What can be lost forever

The lively nodules

Once thought of as a desert devoid of life, the seabed is now estimated to have an extensive range of biodiversity. A 2016 study found a statistically significant correlation between aquatic life in the CCZ and nodule abundance.

The sediment plume

As the robot moves across the ocean floor, sediment clouds are stirred up and can irritate filter-feeding animals such as the corals and sponges that make nodules their home.

Regrowing corals

Bamboo corals on seamounts, as all corals, grow slowly, just millimeters per year. However, plumes distort habitat and can disrupt growth. When the corals are covered by sediment, their larvae will have trouble finding new sites to attach, some scientists warn.

Octopus nurseries

Four octopus nurseries have been discovered at hydrothermal springs around seamounts in parts of the Pacific Ocean near the CCZ. These springs act as a kind of “warm spa” and boost the metabolic rate of developing octopuses, thus speeding embryonic development. These springs are difficult to find, and mining may destroy some undiscovered springs before they can be protected, Orcutt said.

Hydrothermal vents

Mining is targeted at inactive vents, which have unique habitats that are even less understood than the ecosystems around active vents. The Scaly-foot snail, for example, is found only in a 300 square-km patch of the Indian Ocean near certain vents. It is the first animal listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as endangered due to the threat of deep-sea mining.

Essential microbes

The most susceptible species are those that depend on the unique chemistry of the waters that vent from the seafloor. The nodules have evolved symbiotically with microbes that can turn those weird chemicals into food. Mining also threatens conditions for these tiny microbes, some scientists say.

Irreversible damage

In the deep sea, it takes roughly 10,000 years for the ocean floor sediment layer to grow by just 1 millimeter, a process that includes sequestering carbon. The robotic vacuum’s disturbance reaches 10 centimeters into the seafloor, “basically resuspending a million years’ worth of time of carbon,” says the marine biologist Orcutt.

Discharge plumes

The nodules, once collected, are washed and stored on a ship, with the excess sand dumped back into the ocean. Scientists worry the discarded sand could harm aquatic life, including the plankton at the bottom of the food chain and tuna. The Metals Co says it will discharge sediment at depths below 1,000 meters to avoid most marine life.

Industrial noise

Studies show that loud noises can travel as far as 500 kilometers, impacting communications among marine animals like whales and causing behavioral stresses.

Light pollution

On the seabed, the robotic vacuum’s floodlights can harm shrimp larvae, studies have shown. On the surface, light from vessels that support the robots may affect squid and other aquatic creatures, as well as seabirds. More study is needed, scientists say, to understand potential harm from artificial light.

Human impact

In a March 2023 petition to ISA, more than 1,000 signatories from 34 countries and 56 Indigenous groups called for a total ban on deep-sea mining. Some Indigenous island communities are intimately connected to the ocean for fishing and other cultural traditions and oppose deep-sea mining, setting up a conflict with Nauru, the Cook Islands and other island nations that support it.

Is there a better way?

As the world’s hunger for metals and minerals to go green increasingly clashes with the realities of the mining process, the deep sea has become the latest focal point. Ultimately, manufacturers aim to create a circular “closed-loop” system, where old electronics are recycled and their metals are used to build new products.

But reaching that goal is expected to take decades. Debate about whether sensitive ecosystems on land should be dug up have empowered deep-sea mining advocates. Some companies competing with The Metals Co believe that the robotic vacuum is the problem, and are offering potential solutions.

The startup Impossible Metals has developed a robotic device with a large claw that collects nodules as the claw glides along the seafloor. Using artificial intelligence, the robot’s claw is able to distinguish between nodules and aquatic life, the company says.

“From day one, we are focused on preserving the ecosystem,” said Jason Gillham, the CEO of Impossible Metals. However, while the Impossible Metals robot is battery-powered, its energy comes from a diesel generator on a ship at the ocean’s surface, fueling charges that the company’s methods are not fully green.

A Japanese company plans to start mining next year in territorial waters controlled by Tokyo. Chinese officials have acknowledged they lag behind other nations in the deep-sea race, but are vowing to vigorously compete in this “new frontier for international competition.” China is already exploring a massive part of the Pacific seabed west of Hawaii – an area that dwarfs the CCZ. Norway, already a prolific offshore oil producer, is on track to be the first country to allow deep-sea mining if its parliament approves, as expected, plans to mine hydrothermal vents.

For now, the ISA’s members are hotly debating the best standards for deep-sea mining.

“Nothing we do will have zero impact,” said Joe Carr, a mining engineer with the metals consultancy Axora. “We’re going to need mining for the green energy transition.”

Sources:

NOAA Ocean Exploration and Research, the International Energy Agency, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, Beth Orcutt at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, Pradeep Singh at Research Institute for Sustainability, Kira Mizell at U.S. Geological Survey, The Metals Co., Impossible Metals, Natural Earth, Blue Earth Bathymetry, International Seabed Authority, InterRidge Vents Database.

(By Daisy Chung, Ernest Scheyder and Clare Trainor; Editing by Julia Wolfe, Katy Daigle and Claudia Parsons)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments