The mission to create Europe’s battery hub, whatever the cost

Next to fields of corn and sunflowers near the city of Debrecen in eastern Hungary, workers in hard hats pour concrete into the foundations of what will be Europe’s biggest factory making batteries for electric vehicles.

The airport-sized project by China’s Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd. is the jewel in the crown of roughly €20 billion ($21.3 billion) of investments that Prime Minister Viktor Orban says will allow the economy to thrive from Europe’s green transition. Nowhere in the world is ramping up battery production faster on a per capita basis than Hungary.

Yet the plan to become one of the biggest suppliers on the planet goes beyond economics. Environmental activists, community leaders and political opponents say there’s a cost that’s being ignored by a leadership that controls everything from the courts and regulators to the media as Orban seeks to underpin the next era of his rule.

The $7.8 billion facility CATL is building in partnership with Mercedes-Benz AG has been heralded by the government as the single-biggest foreign direct investment in Hungary’s history. Adjacent to the site, two other battery suppliers are building their own plants. Across town, another one, by Chinese firm EVE Energy Co. Ltd., is being put up next to German carmaker BMW AG’s new factory.

Concerns range from the loss of prime agricultural land to the strain on water and energy resources and questions surrounding the disposal of used batteries. Then there’s the potential for accidents at factories working with hazardous materials like lithium.

Town hall meetings on new battery-related investments have descended into shouting matches. Even in strongholds of Orban’s ruling Fidesz party, people have called local officials “traitors.” The government has since changed laws to no longer require in-person consultations.

“Nobody asked us if we wanted this plant,” said Zoltan Timar, the Fidesz mayor of Mikepercs, the suburb of Debrecen nearest the CATL plant. “This may be part of the green transition, but locally what we see is that they’ll be working with hazardous substances. People are scared.”

CATL said it knows what it’s doing, using its extensive experience to ensure that no pollution is released into the air or water. The company also said it would like to work with the local authorities to prevent potential contamination outside the plant.

Yet the anxiety Timar talked of is shared across communities in Hungary, based on more than a dozen interviews with residents, officials and environmental groups, with hardly a corner of the country left untouched in some way by the battery boom.

Scaling up EV production

The tensions highlight the difficulty of going green: while electric vehicles are hailed as a way to cut emissions and slow climate change, there are local environmental costs that critics say are being ignored by a government focused primarily on economic gains.

There are other examples of opposition to the EV revolution. In Germany, Tesla Inc.’s first European plant faced delays as a court considered a legal challenge by environmentalists over the clearing of trees. But under Orban, Hungary is going all in like nowhere else.

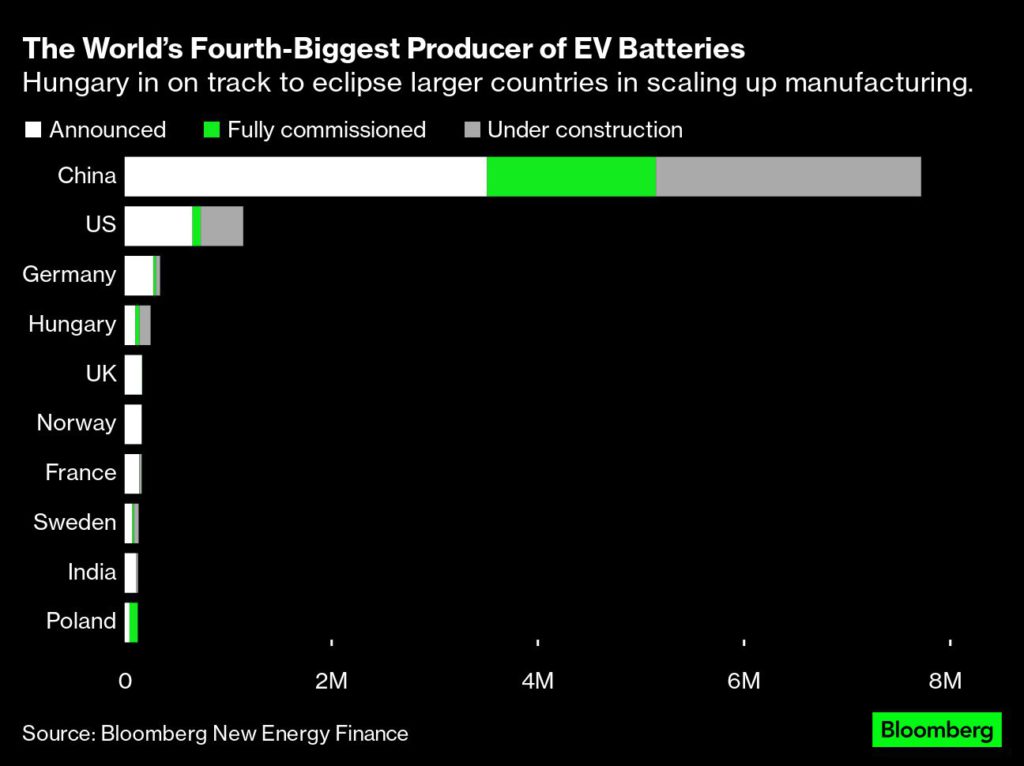

In just a few years, the country of less than 10 million people is projected to become the fourth-largest producer of batteries globally, after China, the US and Germany, according to BloombergNEF data.

Hungary has currently six battery plants that are already producing or in the process of being built. Additionally, there are about two dozen other companies that are part of the production chain that have set up shop.

The first plant to open was in Göd on the bank of the Danube River north of the capital, Budapest. The South Korean conglomerate Samsung SDI converted its plasma screen factory to focus on battery production for EVs in 2017.

The factory borders housing and almost immediately, residents started to raise concerns over noise pollution and alleged water contamination. Years of complaints went largely unheeded as the government and the company pushed ahead, with Samsung SDI doubling the size of its investment.

Teacher Julianna Lam Palla in Göd complained about the smell of “rotten fish” coming from the taps in her house. Though she had no proof the cause was the battery plant, years of being ignored by local officials convinced her to move. “There are so many questions, so much anger and disillusionment,” Lam Palla said as she played with her dog by the Danube.

Things got worse when an opposition party took control of the local municipality in 2019 and promised to look into claims of environmental damage. Orban’s government responded by redistributing the factory’s lucrative business tax receipts away from Göd to surrounding areas.

Activists started measuring pollution themselves and found N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, or NMP, the most common solvent for manufacturing cathode electrodes in batteries, in wells.

“We don’t fear that they’re polluting, we know they are,” said Zsuzsa Bodnar, a vice president of the local environmental group Göd-ÉRT. “Only the authorities refuse to do tests and they don’t accept our results.”

A study published this year in the journal Scientific Reports found lithium in the tap water in cities across Hungary’s 19 counties, though not in quantities hazardous to humans.

After five years of operation, Samsung SDI is now carrying out a comprehensive environmental impact study. The company said it’s applied for a pollution prevention and control permit because its activities have now reached levels that require one.

Samsung SDI is “making continuous efforts to mitigate concerns over the environment of the city of Göd, including water testings that prove no NMP or any other harmful materials are found in water and air, in close cooperation with Hungarian authorities and civil groups,” the company also said in an e-mailed response to questions.

The municipality of Göd, which is now led by a Fidesz-backed mayor again, declined a request for an interview.

Whether the environmental concerns were warranted or not, the argument reverberated across Hungary. To opponents, it underscored the potential risks to communities when a battery plant moves in, and also the cost of resisting it.

The government, meanwhile, has doubled down in its narrative that if you want to revive the Hungarian economy, you need to get behind its plan. Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto, the point-person for these investments, called the battery plants “our life insurance” that the country will come out as a winner from the green transition to electric cars.

“It’s extremely unfair and contrary to the national interest to mislead people and create movements so these factories come not to Hungary but to Germany, France, US, Sweden and who knows where else,” he told an audience of young ruling party supporters.

Hungary has a lot to lose. Orban has spent most of his time in government since 2010 at loggerheads with the EU over the erosion of rule of law in his “illiberal democracy” and flourishing corruption and cronyism. The European Parliament has branded Hungary an “electoral autocracy.” Yet he’s also remained a close ally of German carmakers like BMW and Mercedes, offering tax breaks and lavish subsidies to locate new plants in his country.

Orban’s political choice

The EU has set 2035 as the deadline to stop the sale of new petrol and diesel cars, forcing manufacturers to go electric. Factories that fail to transition risk being shuttered. That has boosted Hungary’s appeal by drawing in primarily Chinese and South Korean battery makers. They can be next to their biggest customers inside the world’s largest trading bloc.

“Battery plants have rapidly come to define Hungary’s economy but they’re also a political choice,” said Andrea Elteto, a researcher at the World Economy Institute in Budapest. “They dovetail with Orban’s goal of connecting East and West in the hope that benefiting firms will work to sustain him in power.”

The CATL plant in Debrecen will be seven times the size of the Chinese company’s only other European factory, in Germany. Production will start within three years, the company said. Laszlo Papp, the city’s mayor, described his region as “where the marriage between the western European car sector and the battery industry is being consummated.”

What residents are concerned about is the cost of those nuptials. Battery plants need massive amounts of water for cooling purposes and unlike most of the other battery plants in land-locked Hungary, the city doesn’t have a large river or lake close by.

Papp said the city has made exhaustive assessments that showed that it wouldn’t run out of water for the plants, nor its residents. But a study by the regional water works published locally said otherwise, predicting that the city’s water resources may be stretched to the limit.

Peter Kaderjak, the head of Hungary’s battery lobby group and a former high-ranking energy official in the previous Orban government, is candid about the risks to the environment. He said the government should even fund monitoring stations where locals demand it. That said, local communities also need to make an effort to understand the economics, he said.

“The point isn’t to make Hungary the world champion” in battery output, said Kaderjak, who helped Orban set up the ruling Fidesz party in the late 1980s in the waning days of communism. “This is positive for Hungary’s economy only in as much as it’s environmentally sustainable and communities feel they gain more than they lose.”

There are signs of change. Last month, Hungarian authorities suspended the operation of the South Korean battery recycling company SungEel Hitech Co. Ltd for a series of violations that threatened the safe operation of the plant. New investors now also need to carry out an environmental impact study.

In Debrecen, the city is building out air and water monitoring stations for the early detection of any potential contamination, a move CATL said it welcomes in a written response to questions.

Activists will take some convincing, though. Next to wooden cabanas summer vacationers rent out by the Danube near Göd, representatives of about a dozen environmental groups from across Hungary were meeting for the first time in August. They were there to learn from the veterans in Göd and to join forces.

“We know we’re not going to be able to stop the world’s biggest battery makers,” said Bodnar, the activist. “But if this is so important for the government, then we also want to have a voice when it comes to drawing up the legal, environmental and safety regulations. We refuse to be ignored.”

(By Zoltan Simon)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments