The mavericks of metals are back, rocking a $15 trillion market

In 2002, the metals industry was jolted into uproar, after a US warehouse owner announced it would start charging a fee to safely buckle up each cargo being trucked from its depots in the London Metal Exchange’s storage network.

Overnight, traders trying to access metal backing the LME’s futures contracts were hit with tens of thousands of dollars in extra costs for work that took a matter of minutes. If any refused to pay, their metal stayed put, meaning the warehouse could keep charging rent. After furious complaints, Metro International Trade Services was reprimanded by the LME for charging to discourage withdrawals from its sheds.

A decade later, Metro was catapulted into the public consciousness at the center of a far bigger firestorm — blamed for orchestrating aluminum delivery backlogs that roiled the LME and at their peak stretched for longer than two years as rivals followed suit. Executives from Metro and then-owner Goldman Sachs Group Inc. were among those dragged to a US Senate inquiry and accused of predatory behavior that distorted raw-material prices for everyone from carmakers to beer companies.

Now, as the metals world converges on London for its annual LME Week gathering, the industry is again fighting over a contentious warehouse fee. And at the heart of the latest controversy lie some of the very same people.

It’s a story that highlights how a small handful of largely private warehouse companies play a critical role in the LME — and how one group of warehouse operators in particular have spent decades finding ways to push the exchange’s rules to the limit in order to maximize their own profits.

Now working at Istim Metals LLC (named for the initials of Metro, backwards) they have introduced a charge that some say is contributing to a squeeze in the aluminum market that is threatening to come to a head in the next two weeks. The situation has drawn in global players including Citigroup Inc. and Squarepoint Capital LLP, and the LME is fielding complaints of unfair practices from some members. At least one party has complained to the UK’s financial regulator.

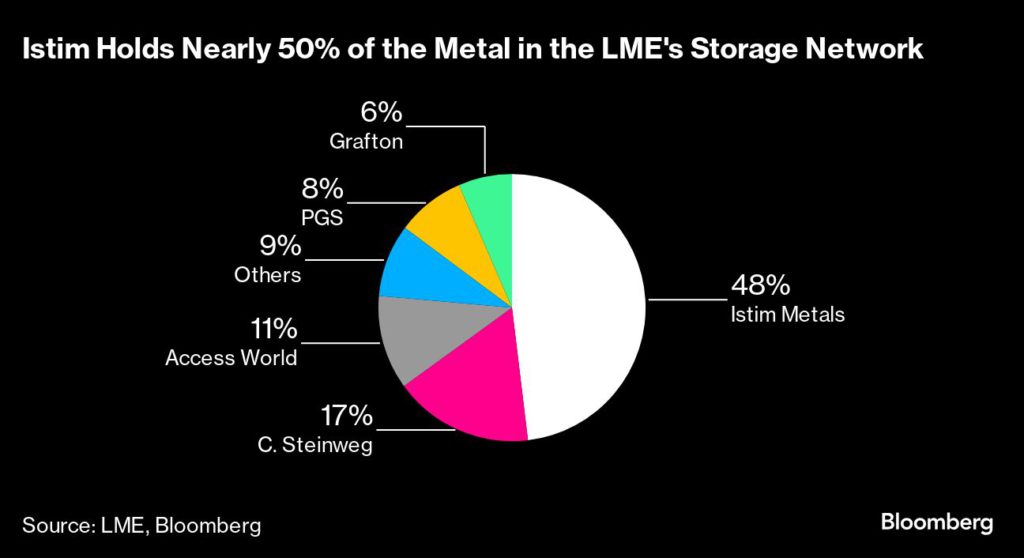

Metro itself has new owners and managers and a far lower profile today. Michael Whelan, whose father William founded Metro, now runs Istim. Much as Metro once dominated LME warehousing, today Istim is so important to the LME ecosystem that it stores roughly half the metal in the exchange’s global network.

Over more than two decades, the Whelan family have become crucial players in metals markets thanks in part to a knack for finding wriggle room in the LME system to attract metal into their sheds and keep it there. The tactics pioneered by first Metro and then Istim shaped the way the market has evolved, leaving rivals following behind and forcing the LME to adjust the rules to keep up.

This story is based on interviews with more than two dozen current and former metals insiders, most of whom asked not to be identified discussing private dealings. Whelan and Istim are described in terms ranging from anger to admiration — and often both. Depending on who you talk to, they are either the bad boys of metals warehousing, or its creative geniuses.

“The sad truth is everyone has learnt to love it, because they’ve realized that these inefficiencies of the market can be traded very profitably,” says a veteran metals trader who lodged a complaint about Metro’s handling fees in 2002 but is contractually restricted from publicly discussing his work at the time. “I shake my head, but in the end, what else would you expect traders to do?”

Istim, Citigroup, Squarepoint and the LME all declined to comment for this story.

The network of privately run warehouses licensed by the LME is designed to ensure that prices on the exchange don’t swing too far from conditions in real-world metal markets, and it serves as a backstop for consumers who need metal at short notice, or producers who want to offload it.

Yet despite its significance as the marketplace where global benchmarks for aluminum, copper and nickel are set — the total notional value of contracts traded in a year is $15 trillion — the LME and its warehouse system regularly turn into a playground for traders.

The games have heated up over the past year, as oversupplied markets meant stockpiles got bigger and a wide discount between spot and futures prices across the key markets creates opportunities to profit by holding onto metal. The more metal that traders have to work with, the more effective their chess moves can be — and the more lucrative they become for rent-hungry warehouses.

In May, Trafigura Group dumped a huge stash of aluminum on to the LME at Port Klang, Malaysia. The move sent the market lurching and was a huge windfall for Istim, but rival players including Squarepoint and Citigroup quickly lined up to withdraw the stockpile, creating a queue that stood at more than nine months by the end of August.

For buyers, queues are inconvenient if they need the metal urgently. But LME rules also say that anyone waiting for more than 80 days can stop paying rent, which means that extra-long backlogs can actually be profitable plays.

If prices shot up, the traders assumed they would re-deliver their metal to the LME. That’s just what happened over the past couple of months, as a spurt of buying sent prices for the main October contract jumping to a premium over the following month.

Istim raised the cost of reregistering metal to $50 a ton, making the manouevre significantly costlier. (The industry norm is $5 to $10. While the LME sets a cap on the rent warehouses in its system can charge, it does not for fees to reregister metal.)

Critics have suggested the charge is intended as a deterrent against removing stock from Istim sheds, and that it is distorting prices on the LME by slowing re-registrations. In its defense, people close to Istim say it’s working within the rules to protect its profits in a low-margin business, and that it’s told customers the charge is negotiable. They argue it’s the traders who are abusing LME rules for free rent.

The company has since halved the fee after receiving an inquiry from the LME, but it’s still roughly three times higher than the norm.

The clash has also revived questions about the potential for conflicts of interest between storage companies and their biggest customers. It’s common practice for warehouses to offer a large slice of their rent — often about half — to the trader that originally delivered the metal, for as long as it remains in the warehouse. That means both parties stand to benefit the longer the metal stays put.

Long position

Trafigura is also a key actor in the current aluminum market, after taking out a large long position in the LME’s key monthly aluminum contract for delivery in mid-October, according to people familiar with the matter.

LME data shows a single long position with more than 30% of the main contract due for delivery in the middle of the month, meaning it would be entitled to scoop up at least 550,000 tons tons of aluminum if it holds the contracts to expiry. That’s more than the amount currently available in the LME’s global warehousing system, and prices for those October contracts have continued jumping —further squeezing the traders in the queue.

Trafigura declined to comment.

For the LME, the shenanigans are an ongoing headache, as it is forced to adjudicate disputes and keep a wary eye on any threats to the orderliness of its market. Yet the exchange’s executives are also keenly aware of the importance of the small handful of companies like Istim that can handle the large mounds of metal flowing through the warehouse system.

At least one party has filed a complaint with the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority, according to people familiar with the matter. The FCA declined to comment.

Merry-go-round Trades

For warehousing companies, business is a constant grind to attract stocks into their sheds and keep it there as long as possible.

When aluminum demand plunged after the global financial crisis, Metro struck deals with traders and producers to stash more than a million tons of unwanted metal in warehouses in Detroit. Rental income started pouring in, and the windfall was so large that it attracted the attention of Goldman Sachs, which bought Metro for $451 million in 2010. (Michael Whelan and Metro CEO Chris Wibbelman stayed on after the sale.)

But it was the plan to keep the metal where it was that catapulted Metro and Goldman into the global spotlight. The company spotted a now-infamous clause in LME regulations: the minimum daily load-out rate to fulfill metal withdrawals could also be read as a maximum.

The discovery, combined with incentives that encouraged “merry-go-round” trades — simply moving metal between sheds — served to kickstart a queue for metal that quickly multiplied across the industry as other traders and warehouses followed.

“It affected not just the North American market but the global market,” said Nick Madden, who at the time was the largest individual buyer of aluminum in the world, as head of purchasing at Novelis Inc. “It was a stark reminder that whatever happens on the LME impacts everyone in the aluminum industry.”

In the wake of the fallout, Goldman sold Metro, which eventually agreed to pay $10 million in a settlement with the LME over the saga.

Michael Whelan, who is now 50, had resigned from Metro by the time the scandal reached fever pitch. He founded the Pilgrimage Music Festival, which is also backed by Justin Timberlake, and has also since invested in a chain of taco stands and a boutique hotel, as well as a copper recycling plant in Spain.

By 2014 Whelan was back in the warehouse business and running Istim. Ex-Metro CEO Wibbelman is also still working closely with the family, but has become less active in the LME warehousing industry.

Back then, the hot game in warehousing was rent sharing. Istim soon muscled in on the action, using the incentives to strike deals for new mountains of metal.

Rent sharing is now widely practiced by warehouse firms across the industry and is a key factor in the calculations for traders trying to make money out of the warehousing system. It’s also a regular annoyance for the LME, which rolled out rules in 2019 restricting how the incentives can be used. At times, however, such as during a 2019 run-in with Glencore Plc, the LME has also sided with Istim during disputes.

“The LME always do what they can to respond to the challenges, but it’s like squeezing a balloon — the air is just going to move somewhere and another problem will appear,” said Madden, the former Novelis executive. “At the end of the day, they can’t change the mindset of the people involved in the market.

(By Mark Burton, Alfred Cang, Archie Hunter and Jack Farchy)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments