The later United States empire

In 1917, the United States created the federal debt limit (or ceiling) to make it easier to finance World War One, essentially allowing Congress to borrow money to pay for the war effort by issuing bonds.

By 1939 with World War Two looming, Congress passed the first aggregate debt limit, but it meant little. For nearly 60 more years the debt ceiling caused nary a ripple, until 2011 when Congress delayed approval of the annual budget, nearly causing a government shutdown. Then a minority in the House of Representatives, Republicans balked at the $1.3 trillion deficit, the third largest in history, so Democrats suggested a $1.7 billion cut in defense spending, since the war in Iraq was winding down. The GOP wouldn’t agree to that, instead offering $61 billion in non-defense cuts including Obamacare. Finally the two sides agreed on $81 billion worth of cuts.

But that wasn’t the end of it. When Standard & Poor lowered its outlook on whether the US would pay back its debt to “negative”, all hell broke loose. Suddenly there was the prospect of the Treasury Department being unable to borrow to pay ongoing expenses, like issuing Social Security checks to vulnerable seniors. Worse, if the Treasury couldn’t borrow to pay interest on the debt, the US might have to default, which would crash financial markets and plummet the dollar, the world’s reserve currency.

While Standard & Poor did lower the US credit rating from AAA to AA+, sending a shock through stock markets, Congress managed to agree to raise the debt ceiling to $16.694 trillion. An expected drop in demand for US Treasuries didn’t happen, nor did interest rates spike, in fact they fell to 200-year lows in 2012.

Since then there have been repeated, and dramatic, clashes over raising the debt ceiling, which is now being used regularly as a political tool to exact budgetary concessions, rather than its intended purpose, to keep a lid on government spending.

2019 was no exception. At the end of December, 2017, Congress hit an impasse over President Trump’s demand for $5.7 billion in federal funds, for a US-Mexico border wall. Trump and the Congress disagreed on an appropriations bill to fund the government for the 2019 fiscal year, or even a resolution to extend passage of the bill. Without appropriations legislation in place, nine executive departments totaling around 800,000 employees were shut down partially or in full. This affected about one-quarter of all government activities. Employees were either furloughed or required to work without pay. The 35-day shutdown was the longest in US history.

The impasse was broken in January 2019 by Trump who finally agreed to a temporary spending deal that did not include $5.7 billion for a wall. In July the House Speaker, Nancy Pelosi, and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer announced a budget deal that raised US discretionary spending to $1.37 trillion in the fiscal year 2020, from $1.32 trillion in 2019, thus avoiding a debt default.

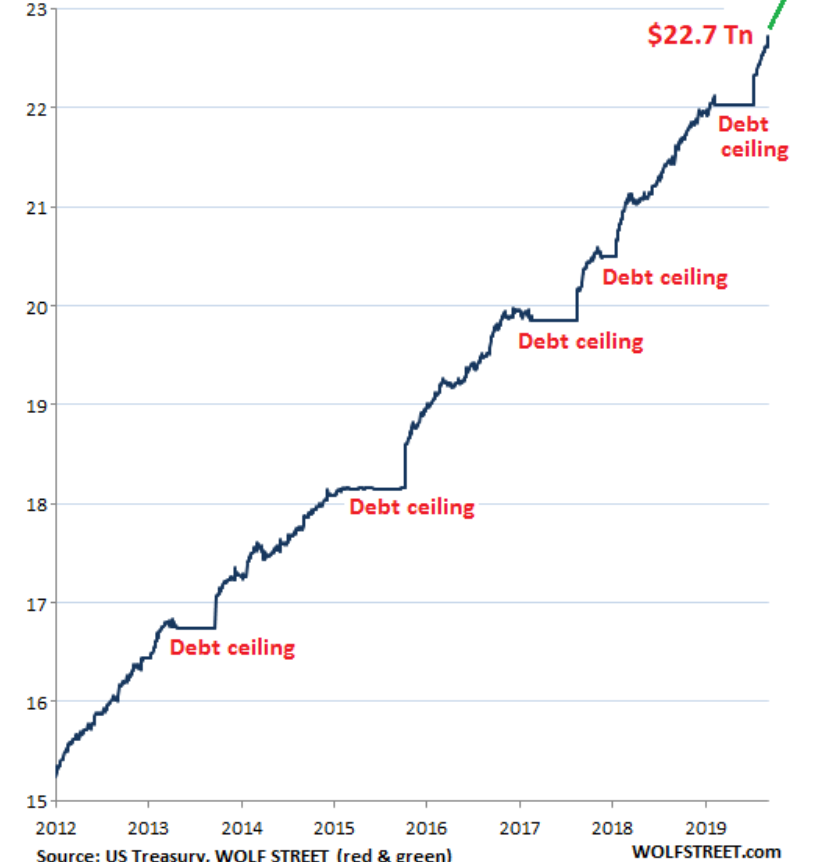

I thought the debt ceiling drama was behind us but the subject surfaced again while checking Wolf Street earlier this week. An article pointed to a report by the US Treasury saying that the US gross national debt jumped by $110 billion in the last two business days of fiscal 2019, and increased $1.2 trillion for the whole year. “This ballooned the US gross national debt to a vertigo-inducing $22.72 trillion,” the article states.

We also learn the debt grew by 5.6% in 2019 and now amounts to 106.5% of GDP, an increase from the 105.4% debt-to-GDP at the end of fiscal 2018.

This is graphically – literally and figuratively – displayed in Wolf Street’s US gross national debt chart, showing the debt climbing steadily from around $15.4 trillion to its current $22 trillion in just seven years. Every year is marked by a new “stair”, indicating permission granted to raise the debt ceiling to pay for expenditures from money the US will have to borrow. It is the epitome of an unsustainable business model – the equivalent of losing money every year, and repeatedly asking the bank to fund your failing enterprise. Eventually the bank is going to say no.

From 2012, the end of the Great Recession, to 2016, the gross national debt climbed, on average, by $947 billion a year. Between 2018 and 2019 the increases averaged $1.23 trillion per year.

The only reason the US has gotten away with it so far is because the US dollar is the reserve currency. Everyone knows if America were to default on its debt, the entire financial system that is based on the US dollar would collapse. The US national debt really is “too big to fail.”

Doomed empires

How did we get here? Well, history is marked by empire after empire that has over-extended itself, militarily; the US is no different.

When the Romans gobbled up Egypt, Judea, Britain and Gaul, the Roman Empire became stretched, with long supply lines requiring more money to maintain. At the beginning of the empire the denarius currency was of high purity, containing about 4.5 grams of silver. However the amount of gold and silver available was limited. When it started to get mined out, the Treasury could no longer meet its expenses. Roman officials though found a way to work around this: by decreasing the purity of the coinage, they could make more coins with the same face value, allowing the government to spend more. But not indefinitely.

At the time of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the denarius dropped to about 75% silver. Sixty years later, it had been significantly debased, with barely 5% silver, the rest bronze. By 265 AD, during the reign of Gallienus, coins only had 0.5% silver in them, meaning it took many more coins to purchase the same amount of goods.

The lower-valued currency also hit the Treasury hard. Its response was to levy steep taxes on the population, leading to political chaos; during the 3rd century there were over 50 emperors, with most murdered, killed in battle or assassinated. With prices inflated by 1,000%, trade ground to a halt, replaced by a primitive barter system. From there the Roman Empire split into three states, weakening it. For the next 200 years barbarians invaded from all directions, killing many Romans in battles or through transmission of plagues. By 476 AD the Roman Empire was dead.

Great Britain also found currency devaluation coincided with the end of its dominion, despite the saying “The sun never sets on the British Empire.”

During the 19th century the importance of the British pound, the world’s oldest currency still in use, grew in relation to Britain’s status in the world. In fact the pound, then the world’s reserve currency, occupied the same place in the global economy as the US dollar does today – even more considering de-dollarization.

As explained by NPR:

During the reign of Queen Victoria, Britain became a major commercial and industrial center. British capital financed railroads in India and Australia, shipping ports in Asia and cotton plantations in the United States. The pound could be used to buy and sell anywhere on Earth.

However the need to maintain far-flung colonies in Africa, India, Southeast Asia, Australia and Canada, drained the government’s purse. After two world wars, especially the extremely costly World War One, Britain’s status in the world declined, along with the value of the pound, symbolized by most of its colonies gaining independence in the early to mid 20th century.

A warring nation

The Roman and British empires were underpinned by strong militaries that both expanded territories and defended them. The same can be said for other empires throughout history – the Akkadians, Vikings, Greeks, Gauls, Spanish, Portuguese and Soviets, to name a few, all seized power by conquering or seizing other lands.

The United States since World War Two has been the bully on the global block – challenged but not yet surpassed in economic nor military power.

Last year President Trump signed off on a huge increase in defense spending. The 2019 National Defense Spending Authorization Act, with a budget of $717 billion, raises America’s troop levels to the highest in a decade. The NDSAA allocated $616.9 billion for the Pentagon, $69 billion for overseas operations and $21.9 billion for nuclear weapons programs.

Among the big-ticket items set out in the act are 77 F-35 Joint Strike Fighters, of which Turkey will receive two of the new jets, $85 billion for the Black Hawk helicopter program, $1.5 billion for littoral combat ships and funding for the Air Force’s new long-range stealth B-21 bomber.

At the time Trump called it the “most significant investment in our military and our war fighters in modern history.”

Big spender

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (Sipri), as the largest military in the world by far, the US has spent an average $650 billion every year since 2010. It spends more on defense than the next nine countries combined.

Of this amount, $400 billion is earmarked for nuclear weapons between 2017 and 2026, which is an increase of $52 billion from the previous 10-year estimate of $348 billion, according to a Congressional Budget Office report.

This year estimated US military spending is $892 billion. However a number of items are not in the actual Department of Defense budget, which can be misleading. For example the DoD budget does not include nuclear weapons spending, black ops, interest on the defense portion of the debt and ongoing spending obligations to veterans. The budget for nuclear weapons falls under the Department of Energy. Other military expenses – care for veterans, health care, military training, military aid and secret operations – are put under other departments or are accounted for separately.

Adding all these items together, actual defense spending is more like $1.2 trillion – around the same amount of new debt that was heaped onto the national debt this year.

Military-industrial complex

Not only does the US have easily the most powerful military with enough weapons to destroy the world many times over – about 6,550 at last count compared to Russia’s approximate 6,800 – it is also the biggest arms dealer.

The US now exports 34% of global arms sales. US arms sales are rising as Russia’s, the next largest arms dealer, are falling.

Indeed military spending is big business – the “military-industrial complex”, a term coined by President Eisenhower, is thriving.

Democrats may call for a shift in priorities away from defense, but cuts are unlikely to happen due to the inertia of military spending that US defense contractors and the United States’ allies have grown used to.

The Washington Post recently published an article that examined this long-running nexus between defense and industry. It found that networks have expanded well beyond traditional “corporate giants bending metal for the Pentagon.” For example since 9/11, more agencies are involved in national security, stemming from the Department of Homeland Security’s creation in 2002-03. Large defense contractors like Lockheed Martin and General Dynamics now deliver a wider range of goods and services to the federal government. WAPO summarizes:

Since 9/11, an increasingly diverse array of firms have a significant stake in federal national security spending. Those funds now flow from a large portion of the federal government and into many sectors of the U.S. economy. If anything, Eisenhower’s complex has become more complex and potentially influential.

‘Normal debt-to-GDP’

Winter is coming

Of course, the United States isn’t the only nation sitting under an immense pile of debt. As debtor nations go, it’s actually around the middle of the pack, in terms of debt-to-GDP ratio. Economists frequently refers to two metrics that reflect a country’s ability to pay for its liabilities: the gross national debt and the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Debt to GDP is the ratio comparing what a country owes to what it produces, on an annual basis. A country that is able to continually pay the interest on its debt without refinancing or hindering its economic growth is generally considered stable. The problem with highly-indebted nations is that creditors (ie. banks and sovereign bond holders) are apt to seek higher interest rates for loaning to countries deemed to be at higher risk of meeting interest payments.

A country with exceedingly high debt may be refused loans altogether.

According to a World Bank study, countries whose debt-to-GDP ratios are above 77% for long periods (remember the US’s is at 106.5%) experience significant slowdowns in economic growth. Every percentage point above 77% knocks 1.7% off GDP, according to the study, via Investopedia.

Conclusion

Everybody these days has a credit card, and most people have more than one. Over-doing it on “the plastic” is curtailed by outrageously high interest rates. Failure to pay the balance each month results in mounting interest charges.

If the US government were to operate like a household, any harmony that existed would abruptly turn into a domestic upon receipt of the Visa bill. You can’t spend more than you make. Ok maybe for awhile, but eventually, the bank will restrict your right to borrow. The United States doesn’t have to adhere to this basic financial rule because it runs on the world’s reserve currency. If expenses exceed revenues, all the central bank has to do is print more money – inflation be damned. Even in 2011, when the country came within a whisker of declaring bankruptcy, investors still rushed out and bought Treasuries, ironically, as a safe haven against a US default.

Washington needs to stop kicking the can down the road and take a hard look at its expenditures. Does the military really need to maintain 700 bases? How many more nuclear weapons are needed to destroy the world? There are already enough to nuke every living thing several times over. Or at least, be honest with the public as to how much is actually being spent on the military. Break it down for us, instead of hiding it.

The US could learn a lot from what happened to Rome; debasement of its currency spelt the beginning of the end of the Roman Empire.

Since the US Federal Reserve was created in 1913, the dollar has lost 95% of its value. Over a hundred years ago a buck was worth a buck; in 2013 it was valued at 5 cents – its worth eroded by inflation – just like the Roman denarius.

Some wise words were written by Huffington Post columnist William Astore, a history professor and retired US Air Force lieutenant colonel. He quotes classicist Steven Willett who sounded a warning to “US militarists and imperialists,” stating:

My personal concern is the misallocation of our resources in futile wars and global military hegemony. We are acting under the false belief that the military can and should be used as a foreign policy tool. The end of US militarism is bankruptcy. I agree with [Andrew] Bacevich’s recommendation that the US cut military spending 6% a year for 10 years. The result would be a robust defensive military with more freed-up resources for infrastructure, education, research and alternative energy. Our so-called defense budget is a massive example of what economists call an opportunity cost.

The US is now about where Rome was in the third to fourth centuries. In his magisterial study “The Later Roman Empire, 284-602: A Social, Economic, and Administrative Survey,” A. H. M. Jones shows what a drain the army was on the [economy of Rome]. By the third to fifth centuries, the army numbered about 650,000 scattered along the limes and stationed at central strategic locations. It took most of the state’s revenues, which had long been declining as the economy in the west declined. And even that 650,000 was far too small for adequate defense of the [Roman] empire.

Military spending feeds into the debt “death spiral” the US finds itself in. But while some fret over the unsustainably high level of indebtedness, others look for opportunity; one obvious beneficiary has been gold.

Investors love gold because it tends to hold its value through time. They see gold as a way to preserve their wealth, unlike paper or “fiat” currencies which are subject to inflationary pressures and over time, lose their value.

And they observe rising levels of US debt as a major deterrent in raising interest rates; the Fed has lowered rates by a total of 0.5% at its last two meetings – a low-rate environment is likely to continue for the foreseeable future, considering the economic uncertaintly both globally and domestically.

Naturally I follow the usual factors that influence gold prices: the US dollar, bond yields, interest rates, inflation, ETF inflows/ outflows, central bank bullion purchases, safe haven demand, etc. As explained in our recent article, a lower gold price before and during China’s Golden Week is an established trend going back seven years, as is the upward price acceleration just after the week ends.

An environment tailor-made for gold investments is being created.

(By Richard Mills)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments