The king of nickel is betting big on a green future in batteries

Tsingshan Holding Group Co. made numerous bold moves on its path to becoming the world’s largest nickel producer, but its new plan to supply carmakers with cheap, clean metal could be its biggest breakthrough yet.

The Chinese company shocked the nickel market twice this month by targeting two significant challenges for makers of electric vehicles and their batteries: first, getting enough nickel, and second, ensuring it’s delivered in a climate-friendly way.

Tesla Inc.’s Elon Musk has said nickel is the metal that concerns him most as he looks to scale up battery-cell production, and last year he promised a “giant contract” for miners to encourage production. Without new sources of supply, the robust EV industry could face a critical shortage within a few years.

Teaming up with Tsingshan would appear to be an obvious choice for Tesla and rivals, but they aren’t just looking for cheap, abundant nickel — they want it to be green, too

“You have, essentially, a market that will grow exponentially in size, but you don’t want to inhibit growth by running short of feed,” said Michael Widmer, head of metals research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. “What we’re seeing in nickel is Tsingshan trying to resolve those issues.”

Teaming up with Tsingshan would appear to be an obvious choice for Tesla and rivals, but they aren’t just looking for cheap, abundant nickel — they want it to be green, too. Nickel is a dirty industry, and Tsingshan’s rise was driven largely by its development of a low-cost production process that’s also extremely carbon-intensive.

Its vow to be greener dramatically demonstrates how the fight against climate change is forcing producers with poor environmental records to find new solutions for more discerning customers. Tsingshan’s financial might and history of innovation suggest that, within a few years, it may emerge as a top supplier of green nickel.

“Tsingshan vigorously upholds and promotes energy conservation, emission reduction, and a low-carbon-footprint environment,” the company said in a statement. “Clean energy produced will be used mainly to power the production of raw materials required for the batteries used in electric vehicles.”

Tsingshan also benefits from solid government support in Indonesia after helping transform the archipelago into a heartland of nickel and stainless-steel production. Now, officials there are courting investments from Tesla and other key players in the battery industry to make sure it plays a similarly critical role in the EV revolution.

The question is whether Tsingshan’s pivot will be sufficiently green to both unlock the investment and solve Tesla’s looming supply shortage. Tesla didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

Tsingshan’s announcements this month lengthen a list of commercial and technological breakthroughs that upended metals markets. The closely held company is owned by a husband-and-wife team, Xiang Guangda and He Xiuqin, and got its big break in the late 1980s with a business making frames for car doors and windows in China’s eastern city of Wenzhou.

Tsingshan is credited with pioneering the large-scale use of nickel pig iron, a semi-refined product and low-cost alternative to the pure metal, to make stainless steel.

Its also benefited from a decision to invest in Indonesia during the 2000s. At the time, the nation’s nickel reserves were unproven, making it a risky move. Now, Indonesia is the largest producer, and Tsingshan runs nickel pig-iron plants and a stainless-steel complex in Sulawesi.

In recent years, it’s been building plants that use acid to make nickel chemicals for batteries, but progress on that path has been slower than planned.

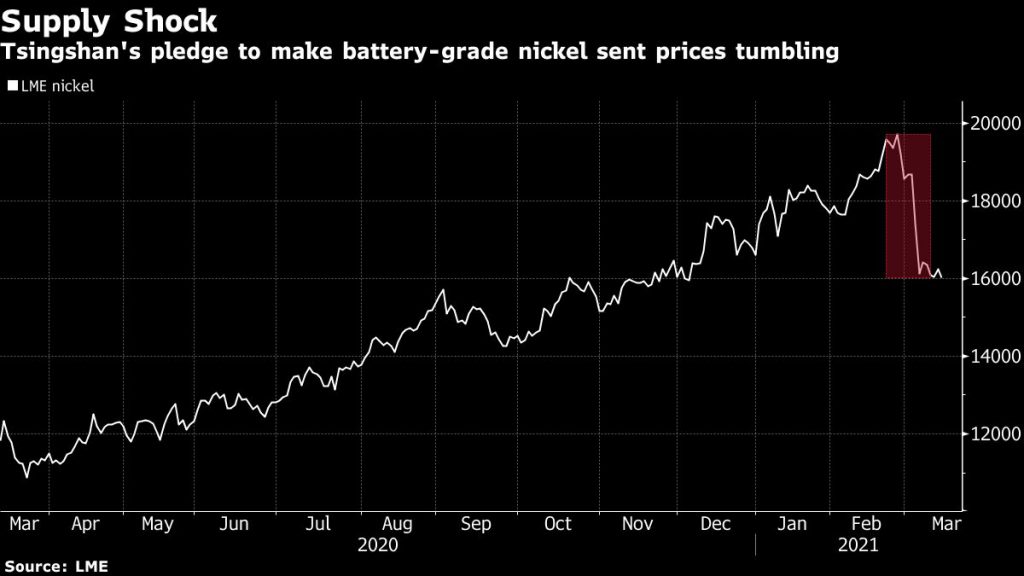

Tsingshan jolted the market earlier this month by saying it planned to make the battery-grade metal using an alternative process, refining it up from materials previously reserved only for stainless steel. Prices subsequently suffered their biggest two-day slump in a decade as investors factored in the additional supply, but there also were immediate concerns about the environmental impact of the process, which relies on vast amounts of coal-fired power.

“There are really big questions about how this process fits into global battery supply chains,” Oliver Nugent, an analyst at Citigroup Inc., said by phone from London. “Will ex-China automakers be willing to purchase this type of material?”

Tsingshan answered those concerns by vowing to operate its plants with solar, wind and hydropower.

To be sure, it’s likely to take a few years to build the solar and wind farms, and Tsingshan hasn’t said when the hydropower plant will come online. So, for now, its method remains a quick-but-dirty solution that buyers like Musk might balk at, and Tsingshan plans to sell the product in China, home to hundreds of EV makers.

Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd., China’s top battery maker, declined to comment.

On their own, the solar and wind projects would be “far from enough to cover for emissions created by production, though a step in the right direction,” said Sasja Beslik, the head of sustainable business development at Bank J. Safra Sarasin in Zurich. The hydropower project will be “both more expensive, and environmentally and socially more challenging.”

Weaning itself off coal and switching to more technically complex production also may raise overheads for Tsingshan, hurting its competitive edge. In addition, there are upfront costs to consider.

The average costs for new renewable-energy capacity in Indonesia suggest that the price tag for of building the wind and solar plant alone could be $2.9 billion, assuming an even split in capacity, according to BloombergNEF.

“This is not an extremely low-cost source of new supply, which is where you would fear a flood of the market,” Daniel Hynes, senior commodity strategist at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, said by phone. “It might now be available to meet the demand, but at what cost?”

Xiang is notorious for battering down costs, though. Nickel pig iron offered a radically cheaper option for making stainless steel, albeit with an immense carbon output.

The average costs for new renewable-energy capacity in Indonesia suggest that the price tag for of building the wind and solar plant alone could be $2.9 billion, assuming an even split in capacity

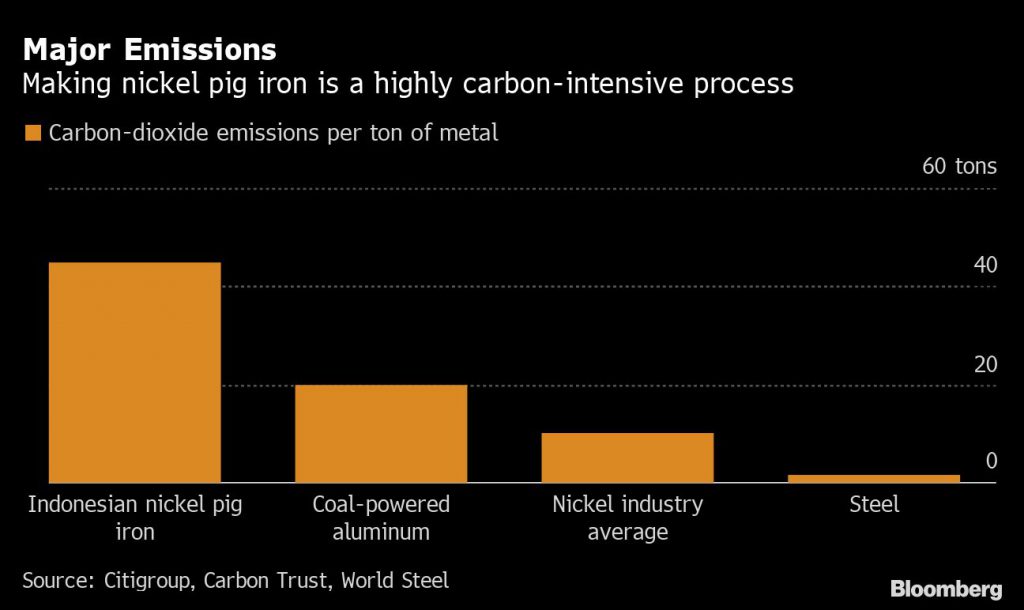

Producing 1 ton of nickel in nickel pig iron would create about 45 tons of carbon-dioxide emissions, according to an analysis by Citigroup. By comparison, steel requires an average of about 2 tons of carbon dioxide per ton of metal, while aluminum requires about 20 tons when coal is used.

Investing in a 2 gigawatt solar-and-wind farm and a 5 gigawatt hydropower plant could help Tsingshan significantly dent its carbon footprint. Together, they’d likely meet most of the power needs for the industrial complex underway in the Morowali region, said Colin Hamilton, managing director for commodities research at BMO Capital Markets.

Those efforts could prove critical for the EV supply chain. The energy transition comes amid a raft of zero-emissions pledges by nations and carbon-neutral commitments by automakers such as Volkswagen AG and BMW AG. Sales of passenger EVs surged 43% last year, and BNEF forecasts a record 4.4 million units being sold this year.

Fresh supplies of battery-grade nickel have ground to a halt in recent years as miners face a litany of commercial and technical setbacks. The only place where supply is growing meaningfully is Indonesia.

Figures from International Nickel Study Group put last year’s production at about 2.4 million tons. During the next decade, miners need to boost annual production by 1 million tons to meet demand from battery-makers, said Jim Lennon, a senior commodities consultant at Macquarie Securities in London.

“I can’t find 100,000 tons worth of projects that are seriously going to get off the ground outside of Indonesia,” he said. “So if it’s not Indonesia, it’s nowhere.”

(With assistance from Chunying Zhang)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments