The coronavirus won’t wreck the commodities market

A rampaging epidemic in the country that consumes about half of the world’s metals has to be bad news for mining stocks, right?

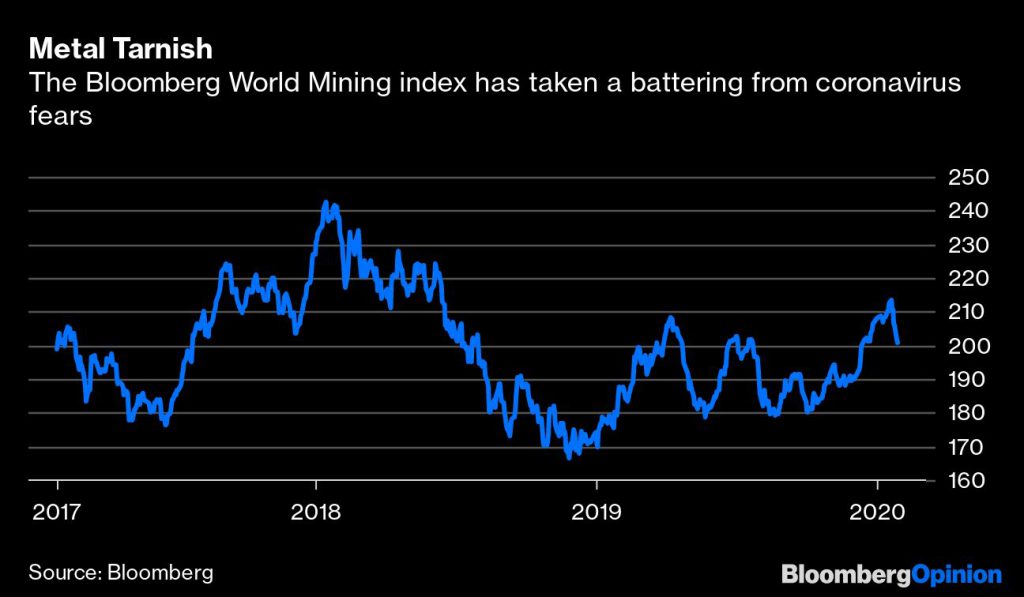

Investors are certainly making that bet. The week started with the Bloomberg World Mining Index falling the most in nearly six months, and a six-day losing streak continued Tuesday on expectations that a slowdown in economic activity will cut China’s voracious appetite for commodities.

Australian shares of Rio Tinto Group fell as much as 5.9% when trading resumed after a public holiday Monday, on track for their biggest slide in three-and-a-half years. Those of iron-ore producer Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. slumped as much as 8.7% in early trading.

That looks overdone. In the grip of an epidemic, it can feel like the sky is falling — but most such viruses die down in a matter of months, and people shouldn’t underestimate how much industrial stimulus Beijing will inject in the economy to keep growth on-target in the aftermath.

Consider Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, which swept through southern China and east Asia in the early months of 2003. Like most coronaviruses — and indeed, most infections of the nose and throat, such as influenza — it exhibited a pronounced winter seasonality, with infections beginning in November and dropping rapidly through April, before approaching zero in June.

Even Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, a coronavirus associated with parts of the world where winter weather is less extreme, showed a relatively similar pattern, with a peak in the early months of the year.

In the grip of an epidemic, it can feel like the sky is falling — but most such viruses die down in a matter of months

Combined with this natural decline is the fact that, despite early surveillance and response lapses, China and other countries are already employing extreme measures to halt the spread. While quarantining of the entire city of Wuhan may not be sufficient — given the disease appears to have spread unchecked until it was too late — that probably won’t be the last attempt to isolate the virus. China’s government, property developers and businesses are likely to implement further measures such as canceling public events and closing commercial and retail spaces.

If things play out this way, it’s not impossible that the epidemic could start to subside in April, just as China’s industrial machine is revving up from its normal winter slumber. Cold weather and the long shadow of the Lunar New Year holiday typically lead to very low levels of industrial activity in January and February, before picking up to full speed between March and June.

In the five years through 2018, for instance, daily pig iron production in March was about 7.4% higher on average than it was in January. Cement output ramps up even more rapidly, as warming weather makes it possible to mix concrete on building sites again: While January and February figures are often too weak to be reported by China’s statistical agency, May output over the same period averaged about 23% above the levels just two months earlier.

That cycle could be particularly pronounced this year. China’s consumers are staying home during what’s traditionally been high season for shopping, dining, seeing films or traveling. A 10% fall in services consumption could cut gross domestic product growth by about 1.2 percentage points, according to S&P Global Ratings.

That could, in theory, put a serious dent in output over the full year, which economists already expect to fall below the government’s target of “about 6%.” It might also violate a long-term pledge to double the country’s GDP by 2020, delivered on the eve of Xi Jinping’s accession to the Communist Party’s highest leadership in 2012.

Beijing is unlikely to take that sort of blow lying down. Just recall the responses to the 2003 SARS outbreak, the 2008 financial crisis, and the overzealous economic rebalancing toward consumption in 2015. As on those occasions, fixed-asset investment (particularly by state-owned companies) is likely to surge to fuel fresh industrial activity. China’s yearlong credit diet — no less serious, in its way, than the one that preceded the 2016 boom — will be loosened to inject some fresh life into a virus-hit economy.

That’s likely to further defer China’s shift to an economy more dependent on consumption and less on mounting debt and carbon emissions — but it will also be bullish, not bearish, for commodities. China’s coal imports in the 12 months through June 2017 were nearly a third higher than in the preceding year; copper rose 12%, oil by 13% and iron ore by 7.7%.

As the virus dies down, don’t be surprised to see that pattern play out one more time. What exactly is it about a country vowing to build two hospitals in a fortnight that makes investors think industrial commodities are heading for the sick bay?

(By David Fickling)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments