The climate change fight is adding to the global inflation scare

The inflation scare that’s become a major theme in markets is getting fresh momentum from the climate-change battle and the huge economic transformation underway.

As governments recognize the importance of climate action and push every corner of the economy to decarbonize, industries from glass to steel to autos are being left with little choice but to change how they make products and ultimately what they sell. The technical hurdles and investment involved mean it’s going to cost much more. Just two examples: Making glass without poisoning the planet costs 20% more, cleaner steel is up to 30% more expensive.

The potential price hit from the green revolution is adding to the arguments about the inflation outlook that are already brewing as economies reopen from pandemic lockdowns and some commodity prices surge to record levels. BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest asset manager, and the Bank of England put the issue in the spotlight this month, while others have also cited environmental demands as one reason why the current inflation pickup won’t be transitory.

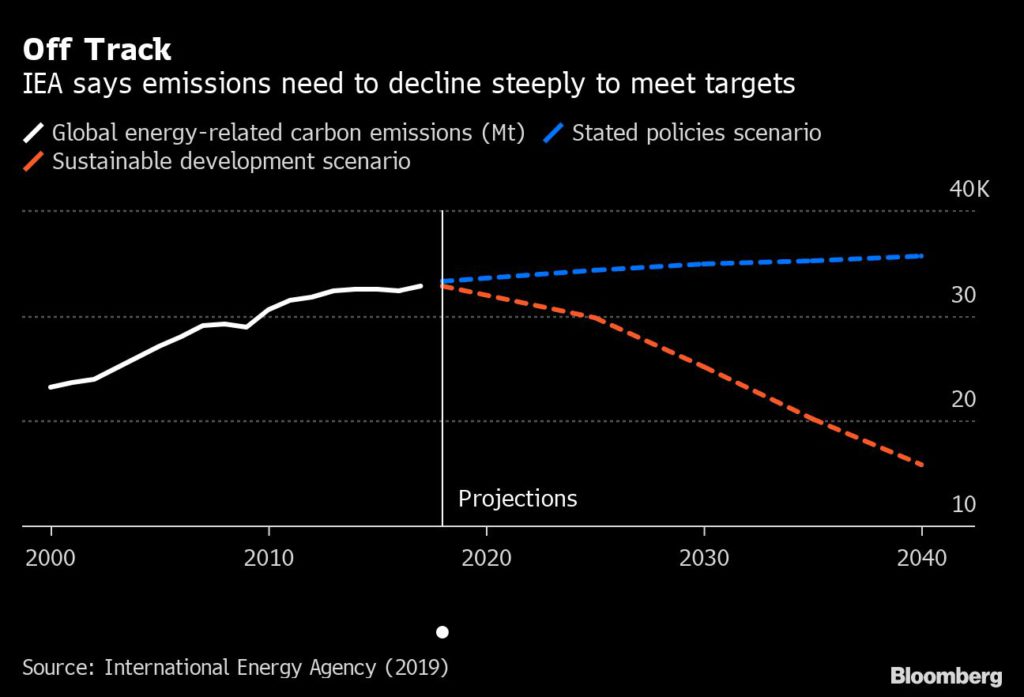

Hitting net-zero targets requires an investment of $5 trillion a year in energy systems by the end of the decade, more than double the average in the past five years, according to the International Energy Agency.

In addition to investment costs, the transition is fueling a huge demand for key raw materials

And there’s another piece to the puzzle. As green-minded investors tell oil companies to scale back drilling, the resulting supply squeeze is seen pushing up oil prices before economies are anywhere near phasing out fossil fuels.

“If I had to put my money on a single factor that was going to push up costs in the years to come, I would say it was the environmental emphasis and in particular the drive towards net zero,” said Roger Bootle, founder of Capital Economics Ltd. and author of the 1996 book `The Death of Inflation.’ “I think this is going to lead to a whole series of costs and price increases across the economy.”

Massive spending on new plants, technologies and processes could all feed through to prices. Manufacturing low carbon glass adds about 20% to the cost, according to Nippon Sheet Glass Co., which supplied the glazed exterior of The Shard, London’s tallest building. That’s a squeeze companies have to either swallow or pass on to customers.

Households are also going to have to spend. In the U.K., the government is drawing up plans to replace conventional gas boilers with more environmentally friendly — and more expensive — heating systems.

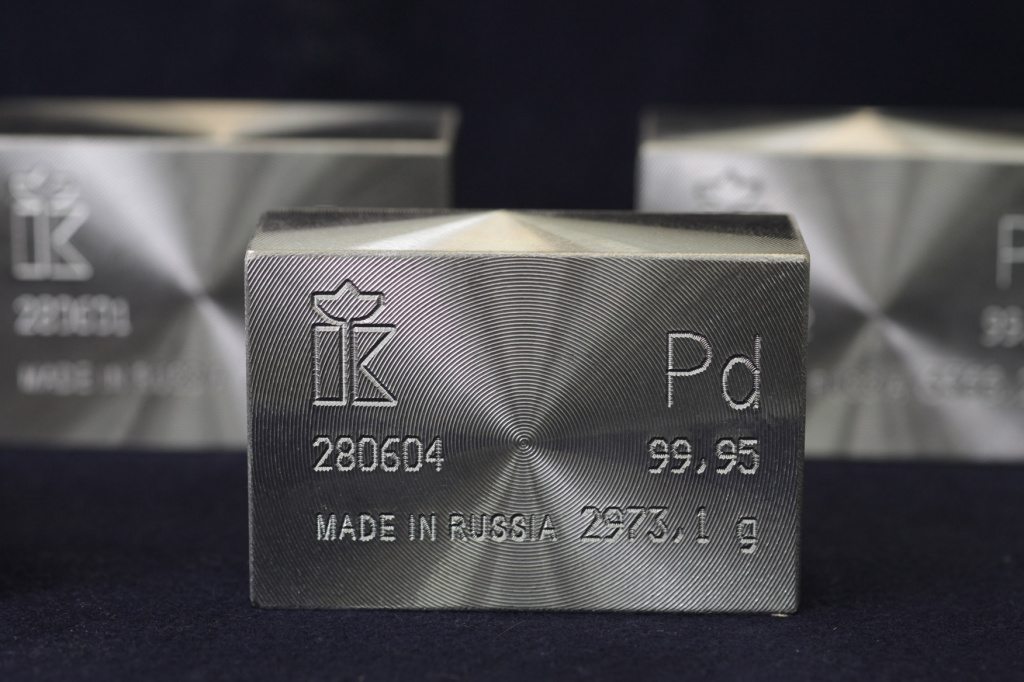

In addition to investment costs, the transition is fueling a huge demand for key raw materials. Copper for example, vital for power grids and wiring for wind turbines, is up more than 60% in price in the past year.

Steel is another case in point. The metal, used in everything from ball-bearings to bridges, is very carbon intensive to produce, normally relying on coal-fired blast furnaces. Greener production routes that use hydrogen or biomass exist, but are currently far more expensive.

That situation could worsen, with the IEA warning last month of a “looming mismatch” between “climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals” such as copper, nickel, lithium and cobalt.

“If our solution is entirely just to get a green world, we’re going to have much higher inflation, because we do not have the technology to do all this, yet,” BlackRock Chief Executive Officer Larry Fink said this month. “That’s going to be a big policy issue going forward.”

How to shift the balance between sources of energy — new versus old, clean versus dirty — will play a huge role in how the transition affects growth and inflation. Major oil and gas producers are coming under increasing pressure from shareholders to cut back on drilling to make credible net zero plans, and lower supplies could push up prices for customers. The inflation hit would be exacerbated if alternative renewable power sources — and the crucial infrastructure to get it into homes and businesses — aren’t ready to pick up all the slack.

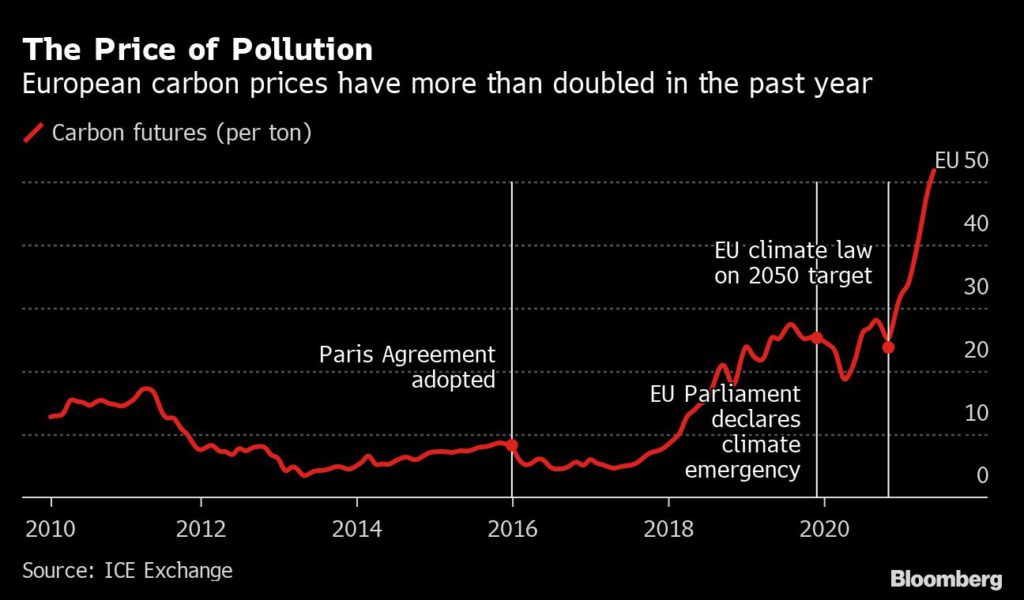

Government carbon pricing policy is another factor in the equation. Under Europe’s Emissions Trading System, companies either pay to pollute, a cost that has doubled in the past year, or invest in new technology to avoid producing carbon. To protect industries from becoming uncompetitive as a side effect of stricter climate policies, Europe now wants to impose a carbon border tax, or penalty for bringing emissions embedded in goods like steel or cement into the bloc.

But even if businesses and consumers have to contend with a price hump as part of the epic energy transformation, it’s unlikely to be permanent. As governments offer incentives, more renewables are used and people change habits, a virtuous circle of production and demand should ultimately improve returns on green investment and reduce costs. In the case of electric cars, BloombergNEF estimates they’ll reach price parity with internal combustion vehicles starting in 2025.

The initial increase in costs to consumers may also be capped as commodities account for only a fraction of the final price of goods. A study by Boston Consulting Group and the World Economic Forum found that decarbonization would add 1% to 4% to end-consumer costs in the medium term.

Falling prices are already being seen in some areas, such as solar power, which is down more than 90% in the past decade.

But while solar has become one of the cheapest forms of electricity, there’s a large upfront cost to installing panels in homes. That hasn’t deterred state lawmakers in the U.S. from making them a key component in the climate change fight. California, for example, requires most newly built homes to include solar systems.

Other U.S. states may follow California’s lead, and some parts of Germany will soon require panels on non-residential buildings. Still, the climate benefits can’t be ignored, plus the long-term savings on utility bills will eventually offset the initial expense.

“In the medium term, it’s still deflationary and that’s where people’s focus should be,” said Edward Lees, who co-manages BNP Paribas Asset Management’s Energy Transition fund. “The wind doesn’t charge you anything, the sun doesn’t charge you anything.”

Central bankers are paying close attention given the impact of climate change and the transition to cleaner energy on inflation, output, jobs and financial stability.

BOE Governor Andrew Bailey said this month that the green shift needs to start as early as possible to avoid a disorderly move later that would be more damaging, where carbon pricing jumps suddenly, companies have to scrap some assets, bottlenecks intensify and output takes a hit. The BOE estimates inflation in that scenario would accelerate to more than 4%, which compares with an average of 2% this century.

Doing nothing also carries huge economic risks. Climate scientists warn of increased frequency of extreme weather conditions, which can disrupt food supplies and damage buildings and infrastructure, all with a fallout on the broader economy.

Analysis from the Network for Greening the Financial System, a group of more than 90 central banks, estimates a global GDP hit of up to 13% by the end of the century if the green transition fails, even before accounting for damage from severe weather events. Amid such warnings, there’s more to consider than costs, according to Rain Newton-Smith, chief economist at the Confederation of British Industry lobby group.

“That’s just looking at that in isolation and not thinking about the huge wider benefits through better air quality, through helping to tackle climate change by reducing carbon emissions,” she said.

(By Rachel Morison, with assistance from Will Wade, Ann Koh, Catherine Bosley, Will Mathis, Tom Hall, Isis Almeida and Eddie Spence)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments