Tesla strikes deal to buy cobalt from Glencore for EV plants

Tesla Inc. will buy cobalt from from Glencore Plc, the world’s biggest miner of the metal, as the carmaker looks to avoid a future supply squeeze on the key battery metal, a person familiar with the matter said.

The contract will help Tesla shore up its cobalt supply for new plants in China and Germany, said the person, who asked not to be identified as the details are private. The opening of Tesla’s so-called gigafactory in China this year has helped propel its shares to a record, as investors turn bullish on Elon Musk’s ambition to transform the company into a global mass-market automaker.

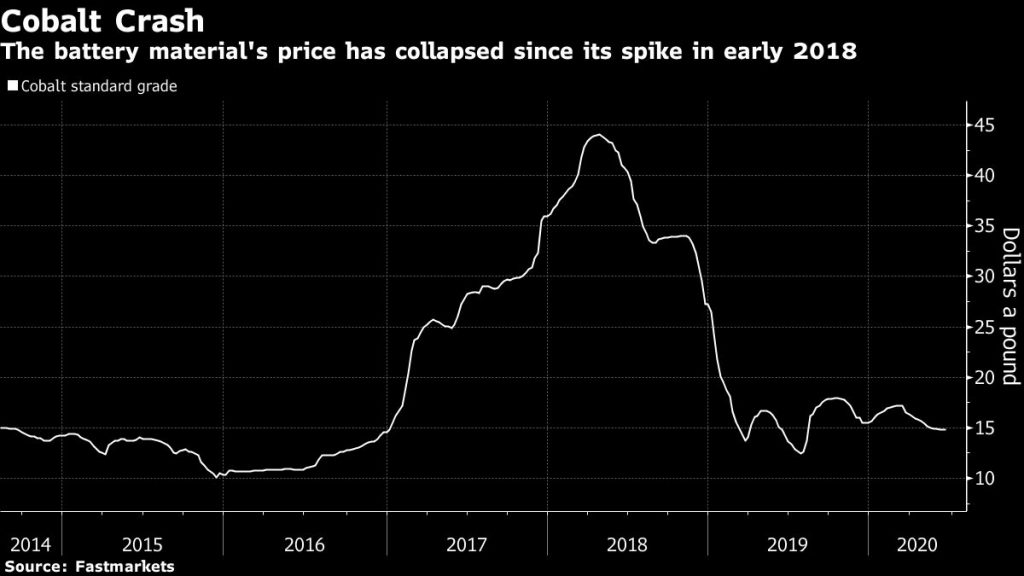

While there’s enough cobalt supply for now, demand is expected to surge in the coming years as Tesla expands in China and Europe and Volkswagen AG to BMW AG roll out fleets of electric vehicles. Warnings about long-term shortages caused cobalt prices to spike in 2017 and 2018, prompting Musk to work on reducing Tesla’s reliance on the metal. Even so, the accord signals that the metal will remain key to the company’s expansion over the next few years.

While Glencore is in a prime position to benefit from a boom in electric-vehicle sales, it has so far struggled to make that happen

The deal could involve Glencore supplying as much as 6,000 tons of the metal a year for lithium-ion batteries used in electric cars, the person said. Executives from the two companies had previously been hammering out terms for Glencore to supply raw materials for vehicles being produced at Tesla’s car facility in Shanghai, people familiar with the matter said in January.

Glencore declined to comment and Tesla didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. The Financial Times earlier reported details of the agreement to sell material for use at Tesla’s new factories.

The accord is in line with other recent contracts the trader-cum-miner has struck, including a four-year deal in February to supply as much as 21,000 tons to battery producer Samsung SDI Co. Ltd. Glencore last year agreed multi-year plans to sell about 30,000 tons of cobalt to SK Innovation Co. and at least 61,200 tons to China’s GEM Co. BMW AG also agreed to buy cobalt directly from Glencore’s Murrin Murrin mine in Australia.

With Tesla’s China plant expected to manufacture 1,000 to 3,000 cars per week, that would translate to about 1,200 tons of cobalt demand annually at full capacity, BloombergNEF analyst Kwasi Ampofo said in January. LG Chem Ltd. and Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. have agreed to supply batteries for the Shanghai factory. Tesla’s Germany plant near Berlin may produce about 500,000 vehicles a year once complete.

While Glencore is in a prime position to benefit from a boom in electric-vehicle sales, it has so far struggled to make that happen. The company booked losses last year related to cobalt after prices collapsed in mid-2018 from too much supply. In November, it shut one of its cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo for a maintenance program that could last two years.

After customers reneged on contracts in response to the price slump, Glencore spent last year locking in new long-term deals throughout the electric-vehicle supply chain.

Direct deals with miners are rare in the auto sector, and the agreements between Glencore, Tesla and BMW signal carmakers are concerned about securing sufficient supply from ethical sources. Almost three-quarters of the world’s cobalt comes from the DRC, and as much of 20% of the country’s output is produced at informal makeshift mines where fatalities and human-rights abuses are commonplace.

The nation is pushing for more influence over the supply chain and a bigger say in pricing. For example, it’s moving to centralize trading cobalt output that’s produced by about 200,000 artisan miners.

Tesla has begun “to engage directly with smelter and mines,” including in the DRC, on standards around ethical and responsible production, it said in a 2019 Impact Report released last week. The work comes as Tesla expands global vehicle production and extends supply chains, the report said.

The company said it will support sourcing of the metal from the DRC if it can be assured raw materials are coming from operations that meet social and environmental standards.

(By David Stringer and Thomas Biesheuvel, with assistance from Chunying Zhang and David Malingha)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments