Supply-chain fragility sends tin price soaring to new highs

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

A New Year and a new record high for the tin price.

London Metal Exchange (LME) three-month tin hit its latest milestone of $44,200 per tonne on Jan. 21 before suffering a bout of vertigo at the start of this week.

It has since regained its bull composure, last trading around $42,500, still more than double the price this time last year. Cash metal continues to command a hefty additional premium.

Tin is experiencing scarcity pricing, having been in the grip of a prolonged supply-chain crunch since the start of the coronavirus. Lockdowns boosted demand for home electronics, all containing tin solder, and simultaneously disrupted a small, globally concentrated supply base.

The resulting squeeze on availability has generated unprecedented degrees of tightness both on the LME and in the physical market.

This should be the year that the supply chain starts to heal but it could be a slow and painful process.

Indonesian delays rattle market

The latest price highs were triggered by news that Indonesia, the world’s largest tin exporter, is delaying new export permits due to administrative problems.

This is not the first time Indonesian bureaucracy has disrupted tin shipments but it is currently threatening one of the few potential sources of significant extra supply this year.

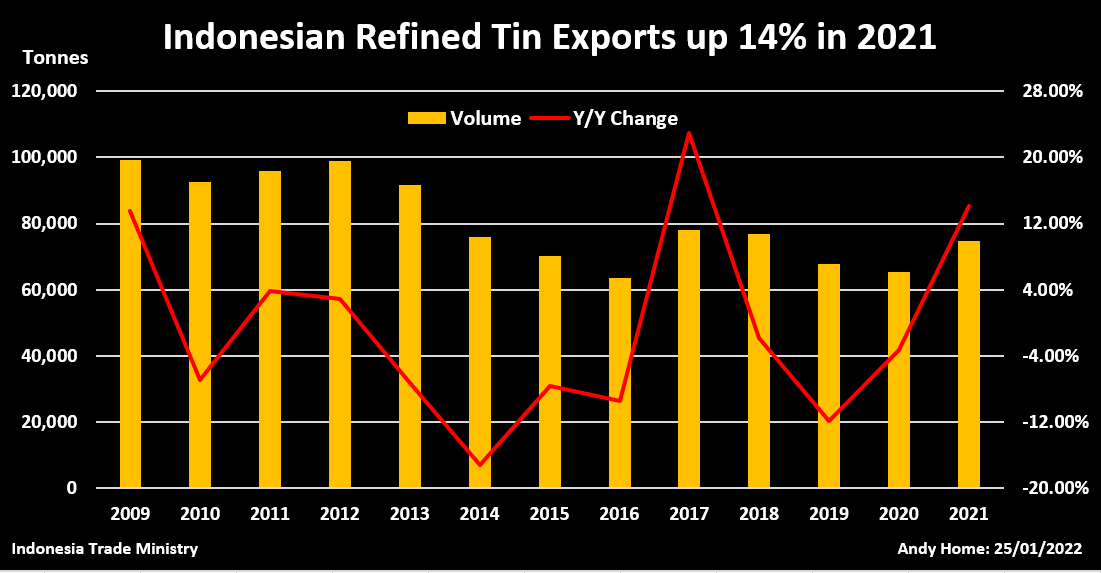

Indonesia lifted exports incrementally over the course of 2021 as operators recovered from covid-19 impacts and the price incentive grew ever larger.

Full-year shipments were 74,674 tonnes, up 14% on 2020 and the highest annual total since 2018.

A depleted supply chain really needs Indonesia to get back on administrative track as soon as possible, given its dominant export role and its evident ability to flex production higher.

The market is also looking for a turnaround at Malaysia’s MSC, which was plagued by a combination of lockdowns and operational issues last year. A six-month force majeure on shipments was due to be lifted on Dec. 20.

China lifts output

China, the world’s largest producer, has also responded to tin’s stellar price rally.

Refined production rose by 11.7% to 174,000 tonnes last year, according to a survey of 20 smelters conducted by state research house Antaike.

The country’s exports boomed, providing some welcome relief for starved buyers across Asia.

Outbound shipments more than tripled year-on-year to 13,882 tonnes in the first 11 months of 2021, making China a net exporter for the first time since 2019.

However, the export surge abated during the fourth quarter and China reverted to being a net importer of refined metal in both October and November.

That suggests renewed issues with China’s own supply chain into Myanmar, a key source of raw materials for many Chinese smelters.

Flows of tin concentrate have been affected by sporadic border closures between the two countries, most recently in November, when Myanmar import volumes plunged by half to just 7,000 tonnes.

Raw materials availability has tightened and at least one Chinese producer – Gejiu Kaimeng – is taking a maintenance break, according to the International Tin Association.

Stocks still low

The Myanmar-Yunnan border crossing is proving to be a lingering covid-19 bottleneck and one that is preventing the mainland market from normalising.

The Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE) tin contract, which has been hitting its own series of life-time highs, remains in steep backwardation across most of the forward curve.

Exchange inventory is still very low at 2,471 tonnes, down from 5,152 tonnes a year ago and a March 2021 peak of 8,853 tonnes.

Higher refined production has so far been absorbed by a combination of exports and physical demand, making little discernible impact yet on ShFE warehouse stocks.

So too in Western markets.

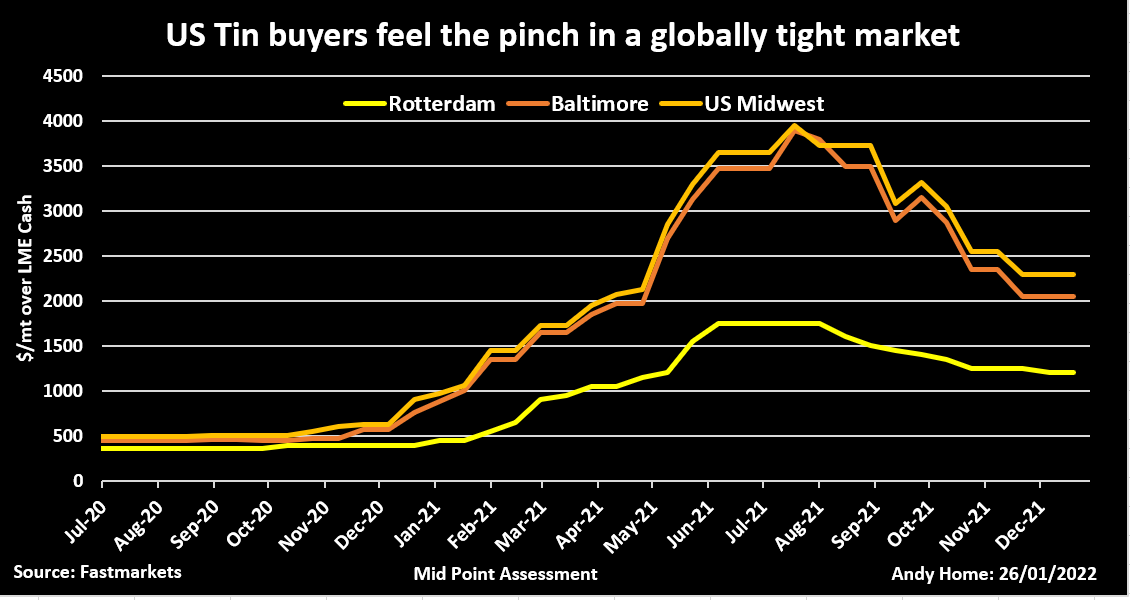

Physical premiums have come off their mid-2021 highs, Fastmarkets assessing that for the United States Midwest at $2,100-2,500 per tonne over LME cash, compared with $3,600-4,300 in August.

The premium for Rotterdam material has also eased to $1,000-1,300 from $1,500-2,000 over the same time frame but these are still very high levels by any historical yardstick.

Physical buyers are evidently still hungry for metal, which is why LME tin stocks are struggling to rebuild significantly from their bombed-out low of just 670 tonnes in November.

Total exchange inventory has edged higher to 2,195 tonnes but arrivals have only trickled in and often what has been warranted has just as quickly been cancelled and loaded out again.

Cash LME metal is still commanding a $451-per tonne premium over the three-month price, which would be extraordinary in any year but the one following 2021, when it exploded out to $6,500 at one stage in February.

A new price paradigm

Tin remains a de-stocked market and low inventory cover leaves it super-sensitive to even the smallest supply-side surprise such as the permits hiccough in Indonesia.

The supply chain is also highly fragile, dependent on MSC’s operational recovery and the potential for more disruption to tin concentrates flows across the Chinese border.

There’s a lot that could go wrong with supply in a year when the market really needs everything to go right.

Analysts are increasingly looking further into the future and wondering where the extra metal will be found to meet demand from both fast-growing electronics and energy transition technologies.

There is an evolving collective rethink about where the price needs to be to incentivise a sustainable supply response.

Analysts at Fitch Solutions, for example, expect tin prices to “ease slightly from spot levels in 2022” but to remain historically higher before rising to $35,500 per tonne by 2030.

That would represent a near doubling of the 2016-2020 average of $18,729, a necessary requirement to invigorate a thin project pipeline, according to a Nov. 2 research note from the ratings company.

It would also represent a significant discount to the current price, which tells you the market thinks even the immediate risk to supply is still skewed to the upside.

(Editing by Kirsten Donovan)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments