Supercharged commodity boom: Definitely. Supercycle? Not exactly

A surge in commodity prices has Wall Street banks gearing up for the arrival of a new supercycle, but underlying dynamics suggest it isn’t going to be a repeat of the epic China-led boom at the start of this century.

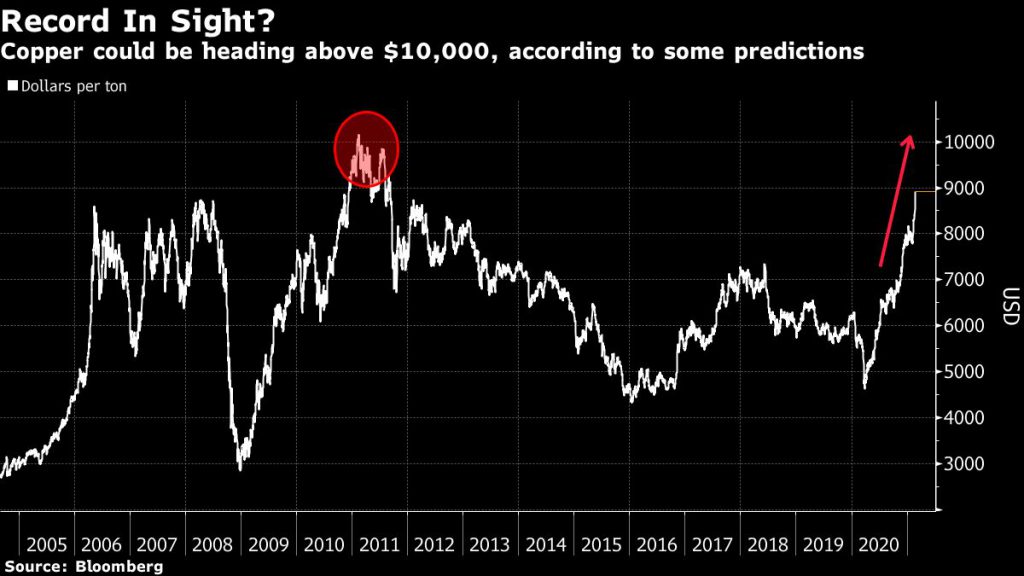

Copper heading for new all-time highs, surging agricultural markets and oil prices back at pre-Covid levels are driving excited talk as economies, juiced by massive stimulus, rev up after Covid-19 lockdowns. The theory is that this could be just the start of a years-long rally in demand for raw materials across the board.

But there are conundrums at the center of longer-term term forecasts. For example, the energy transition that heralds a bright new age for green metals like copper would be built on the decline of a key commodity: oil.

And as investors flock back to markets like copper in anticipation of a growth-led bounce in inflation, policymakers and economists alike are increasingly alert to the consequences of higher food and fuel prices.

While definitions vary, a supercycle is generally viewed as a sustained spell of abnormally strong demand growth that producers struggle to match, sparking a rally in prices that can last years or in some cases a decade or more.

A supercycle is generally viewed as a sustained spell of abnormally strong demand growth that producers struggle to match, sparking a rally in prices that can last over a decade

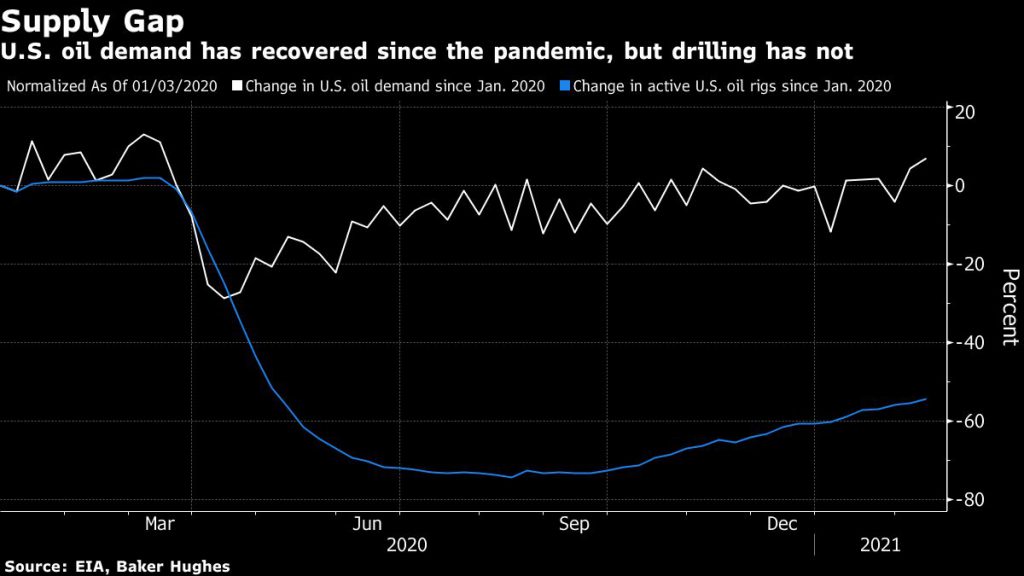

For some analysts, the current broad rally is rekindling memories of the supercycle seen during China’s rise in the early 2000s. But on closer scrutiny, the outlooks for individual commodities are diverging. While it could take copper miners a decade to tap new deposits to meet demand, oil producers from the Permian to the Persian Gulf may prove more nimble, imperiling long-running price gains.

The differing fortunes for oil and metals are already evident in equity markets, with BHP Group Plc, the world’s largest miner, overtaking Royal Dutch Shell Plc as London’s biggest listed company.

“Copper is a proper growth market, hands down; oil is not,” said Michael Widmer, head of metals research at Bank of America in London. “It doesn’t necessarily have to be bearish for oil, but it’s a very different dynamic.”

Goldman Sachs Group Inc., BlackRock Inc., Citigroup Inc. and Bank of America see copper moving back toward all-time highs above $10,000 a ton, and many of the hard yards have already been done. It’s doubled from lows in March to above $9,000, fuelled by bets that demand will spike as the world recovers from the pandemic and governments plough cash into electric-vehicle infrastructure and renewables.

Oil’s rallied too — to above $60 a barrel — as collapsed demand comes back quicker than a deeper and more enduring supply shortfall. Goldman sees it hitting $75 within months, but long-term gains hinge largely on supply continuing to shrink faster than demand as the energy shift gathers pace.

Rallying oil prices are hard for producers to resist. OPEC and its allies had about 9 million barrels a day of spare capacity offline last month. That’s 10% of current global supply. If prices keep rising, there’s little incentive for the group — or its rivals in countries like the U.S. — to keep barrels on the sidelines.

And then there are agricultural commodities that are ruled by their own dynamics. Soybeans and corn have rallied to multi-year highs, driven by relentless buying by China as it rebuilds its hog herd following a devastating pig disease. But much depends on when purchases from China will slow.

Just like in oil, the supply response has become quicker. Seed development means farmers are getting better yields, and crops aren’t as vulnerable to the weather as they used to be.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is already expecting record combined plantings of corn and soybeans this year, and executives from some of the world’s top agricultural commodities traders expect gains to last another year or two.

Supercharged profits

That’s left many advocates for a new commodities bull run honing in on metals, where rallying prices have led to supercharged profits and record returns for miners.

BHP and Rio Tinto Plc handed out $14 billion in dividends last week, but those profits are being generated mainly by iron ore, rather than the more forward-looking commodities such as copper or nickel that some on Wall Street see driving the next supercycle.

And while both have big growth plans in copper, they’re much more cautious on the outlook for other parts of their portfolio. BHP expects steel demand to grow at a similar rate to the global population. It’s a similar story for coal and oil, with the biggest companies in both looking to curtail, not grow, production.

That’s a stark contrast to the start of the last supercycle, when iron ore, coal and oil were the chief beneficiaries of China’s industrial expansion. Those markets dwarf copper in scale, while key battery materials such as lithium that are driving much of the latest hype are smaller still.

Differing fortunes for oil and metals are already evident in equity markets, with BHP overtaking Royal Dutch Shell Plc as London’s biggest listed company

The narrower commodity effect from a new green boom is reflected in the heavy caveats offered by analysts. Citigroup sees a supercycle in copper and aluminum, but more fleeting returns elsewhere. Others including BMO Capital Markets say that while demand could outpace supply for some time, the mismatch won’t last long enough to justify predicting a supercycle.

And even those who are universally bullish on commodities could end up being right for now, even if it doesn’t turn out to be a supercycle. Ultimately, for investors, the long-term discussion may be academic as they pursue the opportunities that exist in the here and now.

“Sometimes the world is just simple,” said Luke Sadrian, a fund manager at Commodities World Capital, who’s been involved in metals markets since 1991. “I’m having the best month of my entire career this month, stuff is moving around that much.”

(By Mark Burton, Thomas Biesheuvel and Alex Longley, with assistance from Agnieszka de Sousa, Grant Smith and Isis Almeida)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments