Stuck with coal pits the world needs, but few want

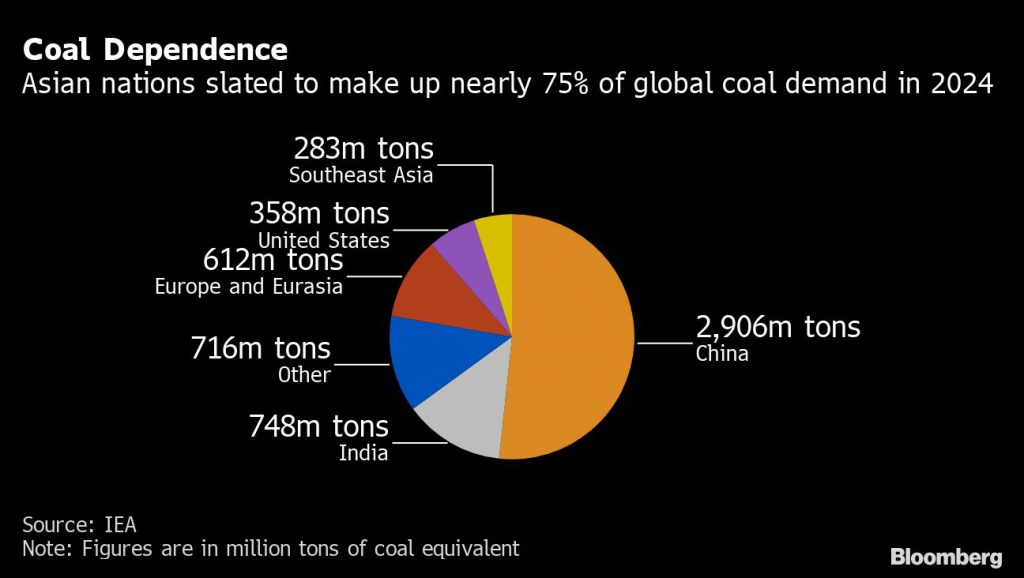

The Mt Arthur coal mine in Australia is one of the world’s best. It’s got plenty of reserves and the low-cost supplies produced there are easily shipped to Southeast Asia, where there’s insatiable appetite for the fuel.

Yet owner BHP Group has a problem: It’s struggling to find a buyer willing to pay the right price.

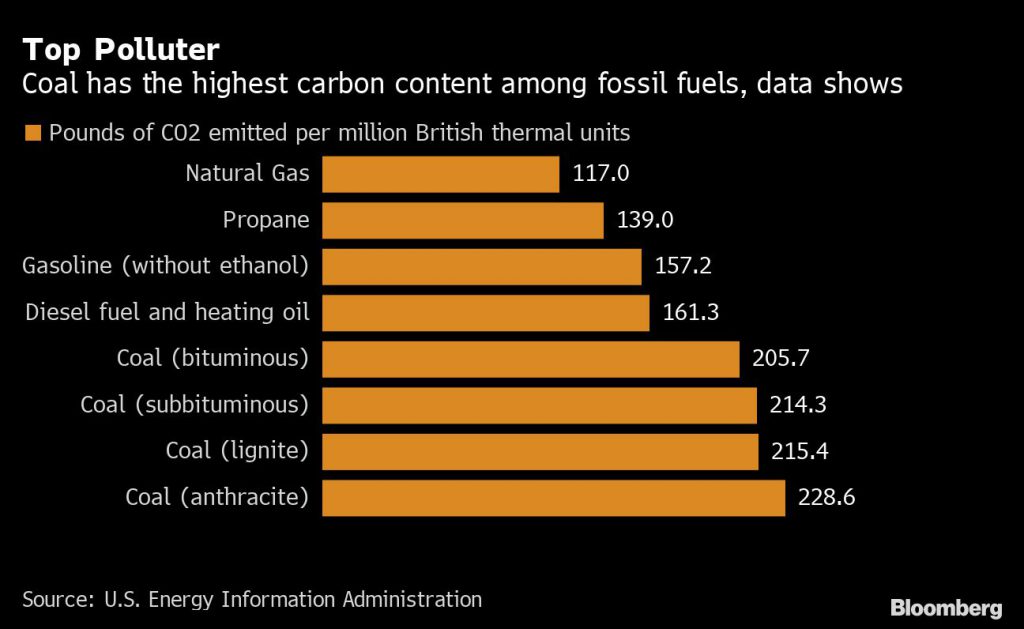

Investors increasingly don’t want to hold shares in companies digging the fuel, which accounts for about 30% of carbon emissions

The world’s biggest mining company’s unsuccessful effort over the past year to offload the asset highlights the predicament producers are in. To bow to mounting investor pressure to exit the most polluting fuel, BHP may need to sell a profitable mine for much less than it believes it’s worth.

Activists have for years said that miners could face a cliff-edge moment by holding onto assets for too long — and that now seems to be happening in thermal coal. While the mines generate plenty of cash and will have customers for years to come, investors increasingly don’t want to hold shares in companies digging the fuel, which accounts for about 30% of carbon emissions.

What’s happening in coal may be a warning to other mining and oil and gas companies about how quickly assets can drop in value as investors rally behind the Paris climate accord. It also presents a risk for resource companies that invest in projects based on the coming decades, rather than years.

Coal-asset values have collapsed quickly. Rio Tinto Group sold its last coal mines for almost $4 billion just two years ago amid strong interest from big miners and private equity groups. Now rivals BHP and Anglo American Plc risk paying the price of waiting too long.

“We could have exited a few years back, and we probably would have got a better price, but we’ve also made good cash flows from what are good assets,” Anglo American Chief Executive Officer Mark Cutifani said. “How we exit is more important to me, in terms of stakeholders and reputation, than getting an absolute number on the bottom line.”

Burning coal is the top contributor to carbon dioxide emissions, causing tens of thousands of deaths a year. While Europe is rapidly turning its back on the fuel, Asian countries like India and China are building hundreds of new power plants and global demand is expected to hold up over the next two decades.

But major miners realize their earnings from coal will ultimately be outweighed by the risk of too many investors dumping their stock. Even Glencore Plc, one of the staunchest defenders of the fuel, agreed to cap output and plans to separate the business should it spook too many shareholders.

There are signs the pool of potential buyers of thermal coal mines is shrinking. BHP rejected early offers from parties including Yancoal Australia Ltd. and Adani Group’s local unit for Mt Arthur that missed its own valuation, Bloomberg reported this week. Anglo American has decided it would be better to spin off its South African coal business rather than finding a buyer with enough cash.

“Who else is going to buy a massive thermal coal mine at this point in time? Is any other mining house going to come in, I doubt it,” said Tim Buckley, a Sydney-based director of energy finance studies at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “Private equity is unfortunately the only answer.”

Writing down

Colombia’s giant Cerrejon mine shows how tough it may be to offload assets. Owned by Glencore, Anglo and BHP, it mainly ships coal to Europe, where the market has been hit by cheap gas prices. Glencore has already written down the asset by $435 million and there are few obvious buyers for such a mine.

With thermal-coal asset values dropping so heavily in recent years, there’s potentially not much more room for prices to drop, said Nick Stansbury, head of commodity research at Legal & General Investment Management, which manages more than 1.2 trillion pounds ($1.5 trillion) of assets. Still, it might make more sense to sell them for less than they’re worth, rather than face investor backlash for holding onto them.

“Companies that aren’t Paris aligned are going to be increasingly bad investments, not because the cash flows are at risk, but because the cost of capital is going up”

Nick Stansbury, head of commodity research at Legal & General Investment Management

More shareholders “are adopting policies that say ‘I don’t want to own companies that produce thermal coal, it is so unaligned with Paris, it is so inconsistent with my investment values,’” Stansbury said. “Companies that aren’t Paris aligned are going to be increasingly bad investments, not because the cash flows are at risk, but because the cost of capital is going up.”

For some diversified miners, the fuel represents little more than a rounding error on overall earnings. Thermal coal accounts for a small fraction of BHP’s and Anglo American’s profits. It’s much more important for Glencore — the biggest thermal coal shipper gets about one-third of its mining profit from the commodity and has been the most resistant to investor pressure.

Glencore billionaire CEO Ivan Glasenberg agreed to cap production to “still have investors.” The company’s management is also prepared to spin off its coal unit should it start to detract from the value placed on its other mines, according to people familiar with the matter, who asked not to be identified as the matter is private.

That would allow it to focus on mining copper, cobalt and nickel, which are seen essential to green technologies.

“Unlike oil and gas, Big Mining does not require complete reinvention,” Deutsche Bank AG said in a note. “In-house energy transition opportunities are available, but M&A would help to improve the opportunity set for some of the companies.”

Still, investor attitudes can change quickly. Two years ago, Anglo American said investors supported the view that the company was best positioned to keep running coal mines the world needs, with local communities set to benefit from better access to health care, water and non-mining related jobs. Now, investors increasingly disagree.

“For us, our thermal coal assets are high quality and well located, but they are our shortest life assets on average, so it’s a rational economic decision and our likely exit is via a demerger,” Anglo’s Cutifani said. “But simply selling assets is not necessarily the best decision for the planet. That’s the reality.”

(By Thomas Biesheuvel, David Stringer and Paul Burkhardt)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments