Steel industry cries for help beyond Trump tariff ‘band-aid’

Donald Trump claims his tariffs saved U.S. steel companies. But with production still slumping and jobs near an all-time low, the iconic U.S. industry is seeking a long-term solution.

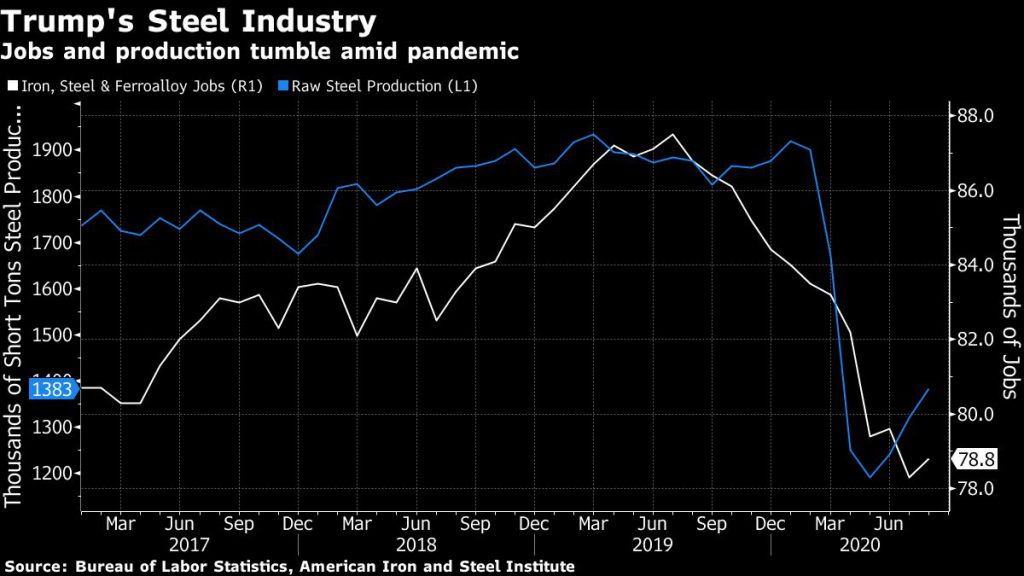

The 25% tariffs Trump introduced in March 2018 gave a brief jolt to American steel producers. U.S. Steel’s annual profit more than doubled that year and the domestic steel price hit the highest in a decade. Jobs rose as much as 9% from the all-time low in April 2017, the month Trump launched a national security investigation into steel imports.

Three years on and pummeled by a pandemic, steel’s gains have stagnated amid a persistent global oversupply. Trump is locked in a close battle with Democratic candidate Joe Biden in battleground states Ohio, Michigan and Pennsylvania, and the votes of blue-collar workers are key to his chances for a second term.

What else needs to be done to really save steel depends on who you ask. Some say keep the tariffs and work with trade partners to put pressure on overproducing nations. Others say a trillion-dollar investment in infrastructure. Some even suggest removing protections altogether and offering support and retraining to workers who lose their jobs.

United Steelworkers union head Tom Conway still has the pen that Trump used to sign the memo back in 2017 that set the tariffs in motion, given to him by his predecessor. While many of his members may vote for Trump in Tuesday’s election, Conway is already working on Biden, whom he joined a month ago for a train trip through Ohio and Pennsylvania.

Conway’s argument to Biden hinges on something that Conway believes Trump hasn’t grasped. “Tariffs aren’t a long-term solution. They’re a band-aid.”

Since a recent peak in the summer of 2019, steel jobs fell more than 10% to a new low of 78,000 in July, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, as producers shuttered at least 10 blast furnaces amid the pandemic. Some of that has since recovered as lockdowns eased and demand picked back up.

Production is on pace to drop 20% from last year, and will be more than 10% lower than 2016, the year before Trump took office. Total capacity — the output if all American mills ran at full blast — is down more than 4%. And the remaining plants operate at only 70% of capacity, below the 80% steel executives say is needed to support healthy profits.

The S&P Supercomposite Steel Index is down almost 15% this year, sending it below the level when Trump was elected four years ago.

“The challenge that eluded the Trump administration so far is what comes next after all of that,” said Scott Paul, the president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing, an industry group that represents manufacturers and steelworkers and was an early backer of the tariffs.

The administration, Paul and others say, has not addressed the main problem: A glut of supply fed by what the U.S. industry has long claimed is predatory overproduction by Chinese steelmakers. That would take coordinated action with allies like Canada, the European Union and Japan — all of which were hit by Trump’s tariffs.

More broadly, economists say the tariffs and the higher cost of steel also contributed to a slowdown in manufacturing growth before the pandemic. In a study published in December 2019, economists at the Federal Reserve Board found the benefits of Trump’s metals tariffs had been more than offset by “larger negative effects” from higher costs and retaliation by other countries.

The Trump administration insists its tariffs have worked to reduce the share of imported steel and protect an essential industry. In a statement to Bloomberg, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who oversees the administration of the steel tariffs, said that since Trump took office at least 34 companies had announced investments in new or existing plans with a total value of $16 billion.

Biden hasn’t said he would remove the tariffs. His campaign said in responses to a questionnaire sent out by the USW he would review them. But he has also said he would put a major emphasis on getting allies like the EU to work with the U.S. to take on China and address the oversupply.

Trump’s negotiations with China and his subsequent “Phase One” deal did nothing to rein in industrial subsidies in China or the “predatory actions of their state-owned entities and their unfair trade practices,” the Biden campaign said. Trump’s aides say the plan is to address subsidies and other structural complaints in future phases of negotiations.

Infrastructure

Biden’s plans also hinge on boosting domestic demand for steel via $2 trillion investment in infrastructure and alternative energy projects, which would be required to use U.S.-made steel.

But there are limits to the impact that “Buy America” programs can have, says Bill Reinsch, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies who years ago helped run the congressional Steel Caucus as an aide to Senator John Heinz (R-PA) and subsequently to Senator John D. Rockefeller IV (D-WV). “Buy America is a very popular phrase. Everyone votes for it and says it’s great and then they go to Walmart and buy imported products,” he said.

Infrastructure spending as well as a post-pandemic recovery in the U.S. economy may indeed boost demand for steel and save jobs. It won’t, however, eliminate the central political quandary: Even a protected industry needs far fewer workers than it once did thanks to a shift to more-efficient “mini mills” and away from huge plants around which whole communities were once built.

Gary Hufbauer of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a colleague last year calculated every steel job saved by Trump’s tariffs cost American consumers $900,000. The U.S. should instead remove protections and deploy generous buyouts of laid off steel workers and economic development plans for affected communities, he said, as well as encourage the industry to focus on high-value specialist steels.

The Trump administration and U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, a former steel trade lawyer, have dismissed a multilateral approach, saying the World Trade Organization and other multilateral venues have been too slow at combating immediate threats.

Foreign imports

Steelmakers argue that the tariffs have done their job limiting the effect of foreign imports, which are near the lowest level since 2009, and that the next administration can’t remove them. But they also say trade partnerships must be established to build off the tariffs in order to stop nations, including China, Vietnam and Indonesia, from flooding the world with excess steel that’s driving down prices.

The next president must keep the tariffs in place, but that it’s going to take a concerted international effort to persuade or pressure countries to change their policies, said Kevin Dempsey, the interim chief executive officer of the American Iron and Steel Institute that represents U.S. steelmakers.

“There is a real divergence happening right now between China on the one hand that is increasing both its capacity and its production, while pretty much all the rest of the entire world, responding to the demand shock caused by Covid-19, is reducing production quite dramatically,” Dempsey said.

(By Joe Deaux, with assistance from Shawn Donnan)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments