Sky-high coal prices won’t spur new mines in a greener world

The highest coal prices in years aren’t enough to spur investment in new mines in the face of heightened efforts by governments and financial institutions to get the world to abandon the dirtiest fossil fuel.

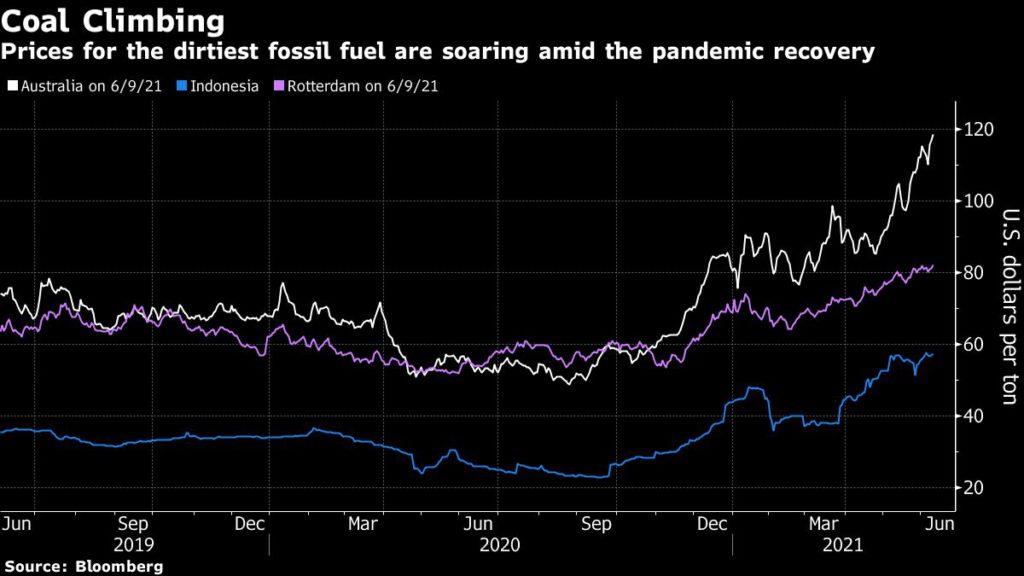

Prices are surging from China to Europe as demand for coal rebounds from a virus-induced hit, and temporary mine outages curtail supply. Yet companies remain hesitant to invest in new projects with financing difficult to come by and question marks over long-term demand.

That’s a boon for miners’ bottom lines but goes against the grain of the typical commodity cycle, where high prices are a signal to increase production and eventually bring the market back into balance. The disruption to normal dynamics underscores how broader environmental goals are changing investment patterns for fossil fuels.

“We expect most coal miners exporting into the seaborne market will seek to absorb the current increase in coal prices to bolster balance sheets, rather than commit to new supply,” said Viktor Tanevski, a principal analyst at Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “There remains a void of projects that are under construction or construction-ready that can be fast-tracked to alleviate price pressures.”

Strong industrial activity in major economies is aiding coal consumption, while supply is being constrained by myriad issues including heavy rains in Indonesia, China’s mine safety push and strikes in Colombia. In Europe, demand has increased 10% to 15% this year after a colder-than-usual winter left gas storage depleted, according to Axpo Solutions AG.

“We expect most coal miners exporting into the seaborne market will seek to absorb the current increase in coal prices to bolster balance sheets, rather than commit to new supply”

Viktor Tanevski, principal analyst at Wood Mackenzie

Futures for high-quality coal at Newcastle port in Australia rose to $118.50 a ton on Wednesday, the highest since 2012. Prices in China, the world’s largest coal consumer, are up 34% since the end of February and have risen so high the government is considering putting a cap on them.

Companies are doing what they can to boost output from existing mines. Indonesia’s PT Bukit Asam said it’s seeking to increase production this year with sales showing positive signals. In the U.S., the world’s third-biggest producer, some assets are underutilized, especially after output slumped during the pandemic, so miners can add more shifts or hire back some workers, said Lucas Pipes, an analyst at B. Riley Securities.

“You won’t find many producers out there who expect we’ll be in a multi-year recovery for coal demand,” Pipes said. “Coal is facing long-term headwinds.”

Even in China, which produces half the world’s coal, giant state-owned miners are shrinking capital spending budgets, said Michelle Leung, a Bloomberg Intelligence analyst. Older, smaller mines across the country are being shut down, and companies are replacing them with larger assets, keeping production capacity relatively steady, she said.

High carbon prices in Europe are making some operations unprofitable, and others are closing as governments seek to speed up the energy transition. German energy supplier Eins Energie in Sachsen GmbH & Co. KG, based in the eastern city of Chemnitz, plans to shut down all its coal-based power and heat generation activities as early as 2023.

One company that is investing in new coal capacity is India’s Adani Group. The conglomerate, which is also one of the biggest renewable power operators in the country, is digging up soil and laying railroad tracks in northeast Australia in order to produce its first coal this year from the Carmichael mine, which will eventually supply 10 million tons a year.

“We have long been confident that population growth and rising living standards in the Asia-Pacific region will drive ongoing growth in electricity generation capacity, especially in India,” said Adani Australia Chief Executive Officer Lucas Dow. “Both coal and renewables will be needed to provide affordable, reliable power while at the same time reducing emissions intensity.”

Adani’s experience developing the project may be one reason why entirely new projects, outside of existing mine sites, are such a rarity. It took nine years from when the operation was first proposed to secure final approvals, and faced scathing public criticism along the way.

At the same time that permitting and building new mines has become more difficult, financing is also increasingly tough, as banks withdraw from the sector to boost their green credentials. That leaves more expensive borrowing via private equity as the only route for the majority of miners who can’t fund new projects from their own balance sheet, said James Stevenson, lead researcher for coal, metals and mining at IHS Markit Ltd.

Even as the world moves away from coal, demand will remain strong through the 2030s and, without new supply, prices are likely to stay high, he said. When the market is squeezed, like now, price spikes won’t incentivize new supply, but will set off mini-waves of coal power plant closures that will kill off consumption until the market rebalances, Stevenson said.

(By Dan Murtaugh, Will Wade and Eko Listiyorini, with assistance from Randy Thanthong-Knight, Krystal Chia, Vanessa Dezem and Jesper Starn)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments