Send in the troops: Congo raises the stakes on illegal mining

A Congolese army officer arrived in the village of Kafwaya in June and warned residents not to trespass on a major Chinese copper and cobalt mine next door. As night fell about a week later, the soldiers moved in.

“They didn’t say anything to anyone,” said Fabien Ilunga, an official in Kafwaya, which is home to thousands of miners eking out a living by illegally exploiting the nearby mineral resources. “The army started to burn down the tarpaulin houses.”

Deploying soldiers to clear tens of thousands of illegal informal miners from mining concessions is a new approach by the authorities in Democratic Republic of Congo, who have wrestled with the problem for decades.

An estimated 170,000 small-scale miners operate across Lualaba, and their numbers appear to be growing

Years of negotiations, alternative employment programs and sporadic interventions by the police have all failed to resolve the issue, which has long been a concern for mining companies sitting on some of the world’s richest mineral deposits.

But using soldiers to keep illegal miners out of vast concessions is likely to be a protracted and potentially violent battle, analysts say. The United Nations has often accused the Congolese army of human rights abuses.

Tech giants and automakers that use Congolese cobalt in smartphones and electric cars are already trying to clean up their supply chains after reports of child labor at informal mines in Congo. Any prolonged violence between soldiers and miners could unsettle investors again.

“Any further involvement of state security forces on mine sites will increase miners’ social risk exposure, which is already probably the biggest risk they face,” said Indigo Ellis, Africa analyst for risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft.

The Congolese authorities say informal miners are endangering the country’s interests and the army deployments are also meant to prevent the kinds of accidents that killed 43 illegal miners at a Glencore project on June 27.

Homes torched

Since the army deployed in southeastern Congo, thousands of illegal diggers have been pushed off Glencore’s Kamoto Copper Company (KCC) mine and China Molybdenum’s Tenke Fungurume Mine (TFM).

In the case of Kafwaya, which is in China Molybdenum’s 1,800 square kilometer TFM concession, local activists said a few days after the army’s initial warning on June 13, soldiers set market stalls ablaze and put up camp nearby.

Less than a week later, soldiers torched dozens of homes belonging to miners and farmers alike and ransacked a school, residents and a local activist group said.

They said the fires severely burned a 3-year-old girl and a 14-month-old boy who were caught inside their homes.

General John Numbi, who led the operation, denied anyone was hurt. Asked later about the specific allegations, he sent a text message that just said: “Let’s be serious.”

China Molybdenum declined to comment. TFM’s deputy general director, Kasongo Bin Nassor, said at a conference last week that the mine had asked the government to do more to secure the concession, but did not request the army be deployed.

He said the mine had been invaded and illegal miners had roughed up TFM employees, damaged machinery and made it hard to access certain parts of the concession.

“Once you have metals that require serious investment, you cannot encourage artisanal mining,” Bin Nassor said.

General Numbi is currently under U.S., EU and Swiss sanctions for reportedly threatening violence against opposition politicians in 2016. He denies any wrongdoing.

Strategic interests

The risk of ending up with Congolese cobalt mined by children in dangerous conditions has already prompted some car companies to look for alternatives.

Tesla is trying to use more nickel – which is mainly sourced from Indonesia, the Philippines, Russia and New Caledonia – and less cobalt in car batteries. Tesla says its next generation battery won’t use cobalt at all.

BMW, meanwhile, said in April it would buy cobalt directly from mines in Australia and Morocco.

General Motors said it did not purchase cobalt directly and referred questions to LG Chem, its battery supplier.

LG Chem said it was using blockchain technology in partnership with automakers Ford Motor Co. and Volkswagen, tech firm IBM and Huayou Cobalt to trace ethically sourced minerals, including cobalt.

Apple said since 2016 its suppliers in Congo have taken part in third-party audits to ensure they abide by a code of conduct. The U.S. tech giant dropped two cobalt refiners and smelters last year.

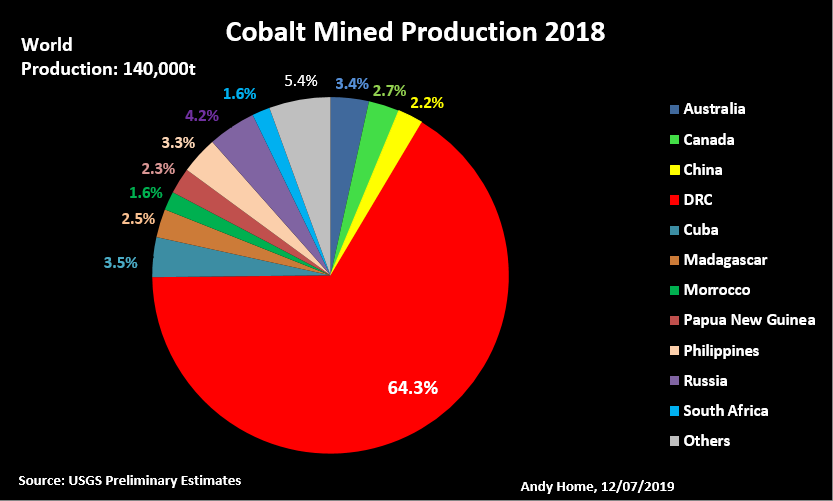

But with 64% of global cobalt supplies coming from Congo in 2018, according to the United States Geological Survey, it will be difficult for companies to cut the country out of their supply chains entirely.

“In the near term, they know and accept that they are going to have to buy cobalt or products at least in some part from the DRC,” said Caspar Rawles, senior cobalt analyst at consultancy Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

Glencore said its KCC concession had not asked the army to intervene and while troops were operating around the mine, they had not entered the site. The army said it had evicted 20,000 miners. The miners responded with a series of protests during which stores were looted and at least 20 people were arrested.

The commodities trading and mining company based in Switzerland referred Reuters to a letter its managing director wrote to Congo’s President Felix Tshisekedi urging Congolese forces to respect human rights and use the least force possible.

IndustriALL, an international union, said its affiliate at KCC had asked regional Governor Richard Muyej to address the issue of illegal miners but said it opposed sending in the army.

“There are strategic interests of the country at stake,” said General Numbi. “If the investors complain … the government will take measures (to deploy the army) if it decides the police cannot handle it.”

Mining alternatives

The industrial copper and cobalt mines in the southeast of Congo are far from the conflict zones in the east of the country where there are gold, tin, tantalum and tungsten mines controlled by militias and army commanders.

Those eastern areas of Congo have already been targeted by U.S. legislation seeking to stop so-called conflict minerals ending up in products such as smartphones.

But analysts say clashes between the army and miners in the copper belt where TFM and KCC are located could further unsettle investors already worried by the reports of child labor and dangerous conditions in artisanal mines.

“It’s not entirely clear whether you can operate a responsible mine inside the DRC or not. I genuinely do not know whether you can,” said one mining investor, who asked not to be named for fear of angering authorities.

Clashes earlier this year between police and stone-throwing miners in the southern Lualaba province, where TFM and KCC are located, killed three officers, convincing authorities that better-armed forces were needed to take on the miners.

Local police and private contractors who are supposed to secure mines are often bought off by the illegal miners and traders, analysts say, strengthening the case for intervention by the army.

The government has sought to convince informal miners to leave the sector in favor of agriculture, and mining companies have offered alternatives too.

Glencore, for example, supports cooperatives working in farming, welding, sewing and carpentry.

But informal miners say they don’t earn nearly as much through these activities and often begrudge industrial mines claiming the richest concessions, sometimes on land where their families have lived for generations.

An estimated 170,000 small-scale miners operate across Lualaba, and their numbers appear to be growing. Often equipped with just shovels, buckets and straw sacks, they burrow deep underground in search of ore. Accidents are common.

“There are cave-ins all the time on many of these sites,” said one official at an industrial mine in Congo. “Wherever there is cobalt in the DRC, there will be artisanal miners.”

In the absence of long-term economic alternatives for the illegal miners, they are likely to return to the concessions, pushing soldiers to resort to ever harsher measures, said one mining consultant, who asked not to be named.

“Displacing artisanals is like whack-a-mole,” he said. “What they will end up doing is just brutalizing the miners in order to make them too afraid to come back.”

(By Aaron Ross, Fiston Mahamba, Ben Klayman, Barbara Lewis, Zandi Shabalala, Stephen Nellis, Alexandria Sage, Heekyong Yang and Joe Bavier; Editing by Alexandra Zavis and David Clarke)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Andrés sorribes

Ulrich beck and his book “society risk”: it’s time to face the book truth… ??