RWE will resist pressure for quicker shutdown of coal capacity

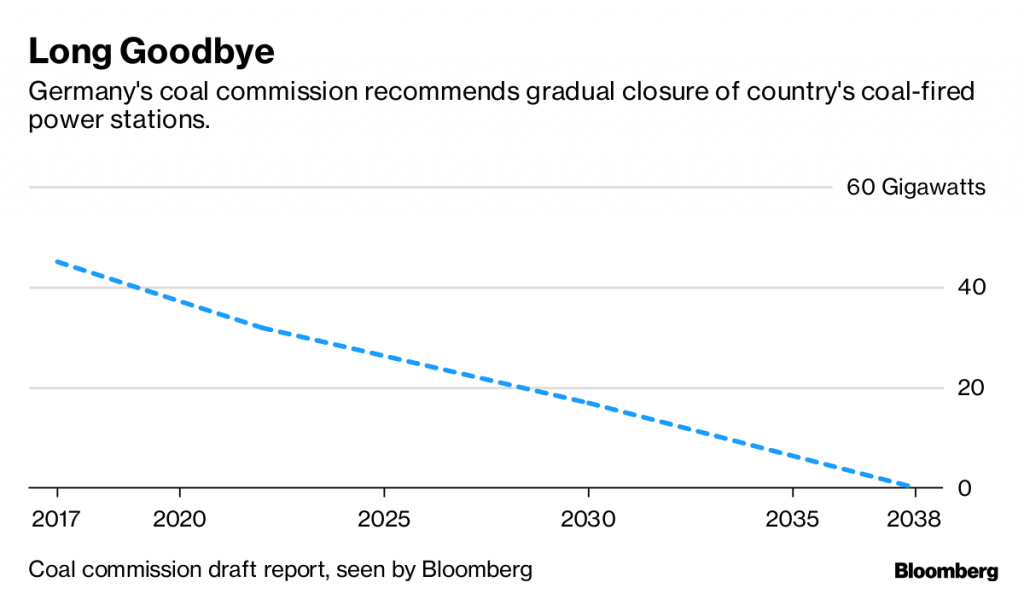

Germany’s biggest power generator will resist pressure from some environmental groups and shareholders for a rapid shutdown of its coal-fired plants much before the country’s deadline to do so by 2038.

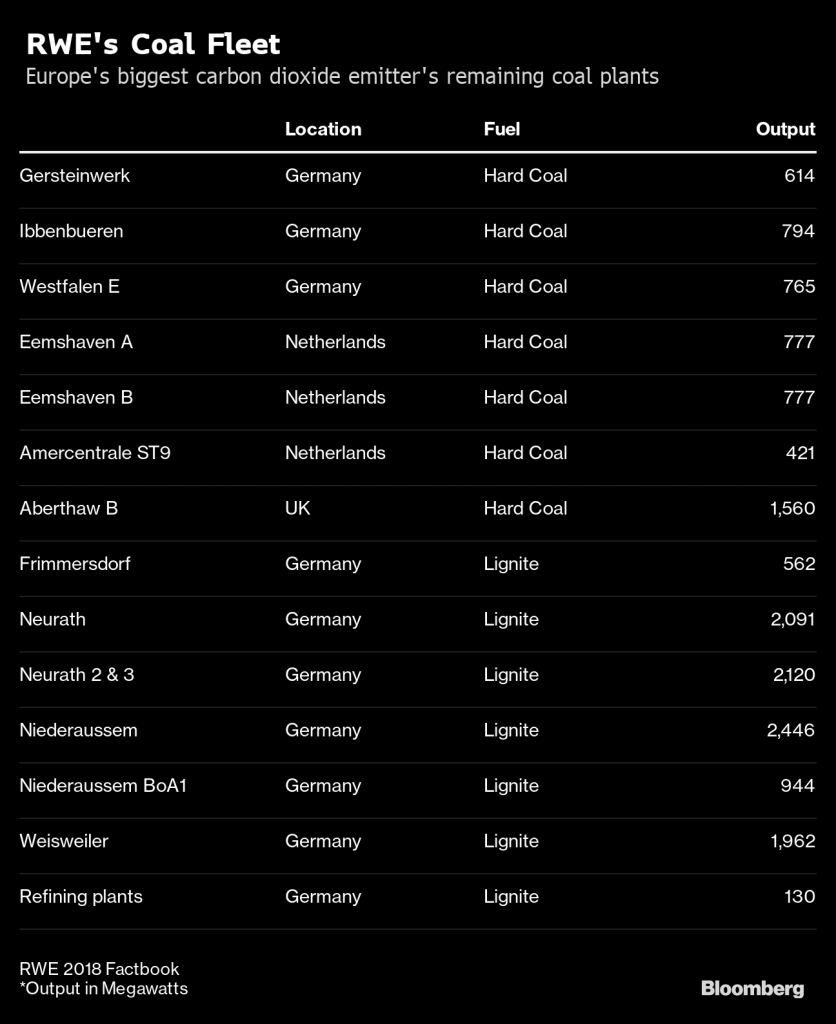

RWE AG, which owns six facilities using the dirtiest fossil fuel, has obligations to workers and municipal shareholders that will prevent quicker efforts to close coal capacity, according to its Chief Financial Officer Markus Krebber.

The remarks highlight the complexity of Germany’s decision to exit from using coal as a power generation fuel, a move that will end thousands of jobs and shutter billions of dollars of assets before their investors have earned their expected return. Utilities and the government are discussing exactly which plants to shut and when, with environmental groups pressing for faster closures.

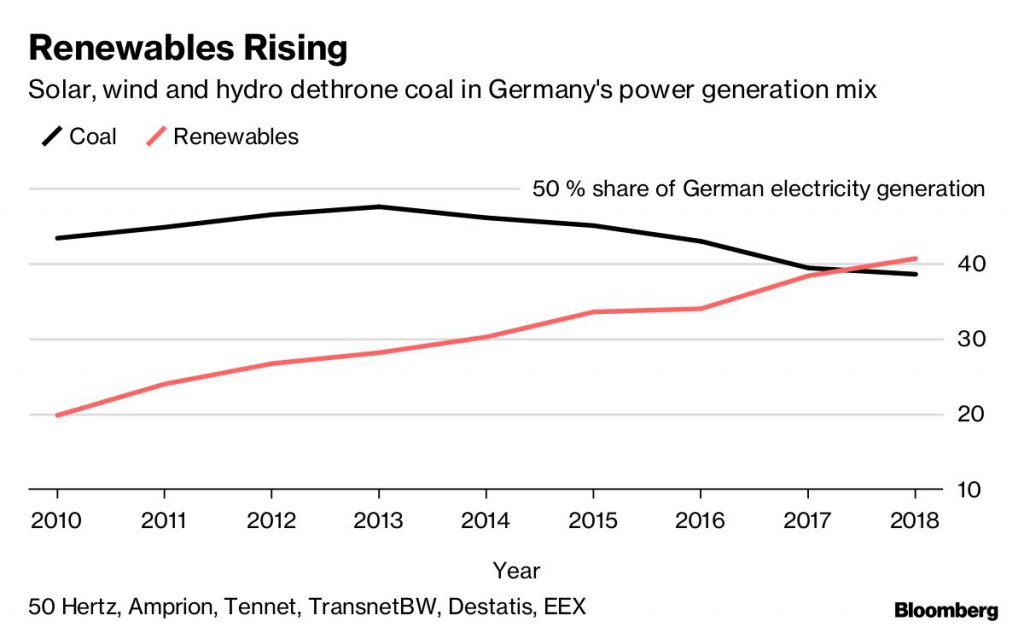

“You can’t just employ a hit-and-run strategy here,” Krebber said in an interview in Frankfurt. The exact date of the exit would rest on the progress Germany makes on shifting its grid toward wind and solar power and away from nuclear and coal plants.

Germany has pledged to quit coal-fired power generation by 2038 in order to meet emissions targets under the Paris Agreement on climate change. RWE has said it would stick to the commission’s recommendations for exiting the fuel and Krebber’s comments suggest the company won’t unilaterally wind down its coal operations much before then.

In September, the company pledged to make itself carbon neutral by 2040. The firm has come under pressure from environmentally-minded shareholders and protesters to quit its hard coal and lignite operations sooner. It was Europe’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide last year, according to European Union Emissions Trading Scheme data.

While Krebber acknowledged some shareholders see risks to RWE’s reputation and finances from maintaining large-scale coal operations, he also said the company employed 70% of its workforce in lignite mining operations and couldn’t abandon them. German corporate law mandates labor union representation and executive board and supervisory board level, constraining management’s room for maneuver.

Some of the company’s biggest shareholders are municipal governments where RWE employs those workers. They are likely to object to a rapid exit from the fuel.

At the end of 2018, RWE’s single-largest shareholder was KEB Holding, which is backed by the City of Dortmund. Its third largest shareholder was the City of Essen with 3% of its stock.

“That’s not something a company like ours — especially given the municipal shareholder tradition — can pursue,” Krebber said.

Discussing Germany’s ongoing coal exit talks, Krebber said the company was now in biweekly talks with the government, adding that the discussions have picked up speed after a slow start.

He said RWE was still seeking 1.2 billion to 1.5 billion euros ($1.3 billion to $1.7 billion) for every gigawatt closed early, but said that could fall if the government decides to deal with payments for workers outside the company.

RWE operates four large lignite plants with 10.3 gigawatts of capacity and three more units with 6.5 gigawatts that burns hard coal. Lignite is a soft form of the sedimentary rock that is the dirtiest form of the fuel. That includes units set aside in a capacity reserve.

“We would have wished for quicker talks because it’s not a big problem to sort it out but we are where we are,” Krebber said. “Now it’s going in the right direction.”

(By William Wilkes, Brian Parkin and Vanessa Dezem)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments