Russia’s war is turbocharging the world’s addiction to coal

In Germany and Italy, coal-fired power plants that were once decommissioned are now being considered for a second life. In South Africa, more coal-laden ships are embarking on what’s typically a quiet route around the Cape of Good Hope toward Europe. Coal burning in the U.S. is in the midst of its biggest revival in a decade, while China is reopening shuttered mines and planning new ones.

The world’s addiction to coal, a fuel many thought would soon be on the way out, is now stronger than ever.

Demand has been on the rise since last year amid a natural gas shortage and as electricity use surged after pandemic restrictions were rolled back. But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine turbocharged the coal market, setting off a domino effect that’s leaving power producers scrambling for supply and pushing prices to record levels.

The boom in the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel has huge implications for the global economy.

The higher prices will continue to feed into rising inflation. But even with the recent surge, analysts say that coal is still one of the relatively cheapest fuels. That’s making it more critical for power supplies at a time when coal burning also remains the biggest single obstacle in the battle against climate change. Meanwhile, miners are struggling to dig up any additional tons as utilities around the world keep demanding more, setting the stage for the next phase of the global energy crisis.

“When you’re trying to balance decarbonization and energy security, everyone knows which one wins: Keeping the lights on,” said Steve Hulton, senior vice president for coal markets at market-research company Rystad Energy in Sydney. “That’s what keeps people in power, and stops people from rioting in the streets.”

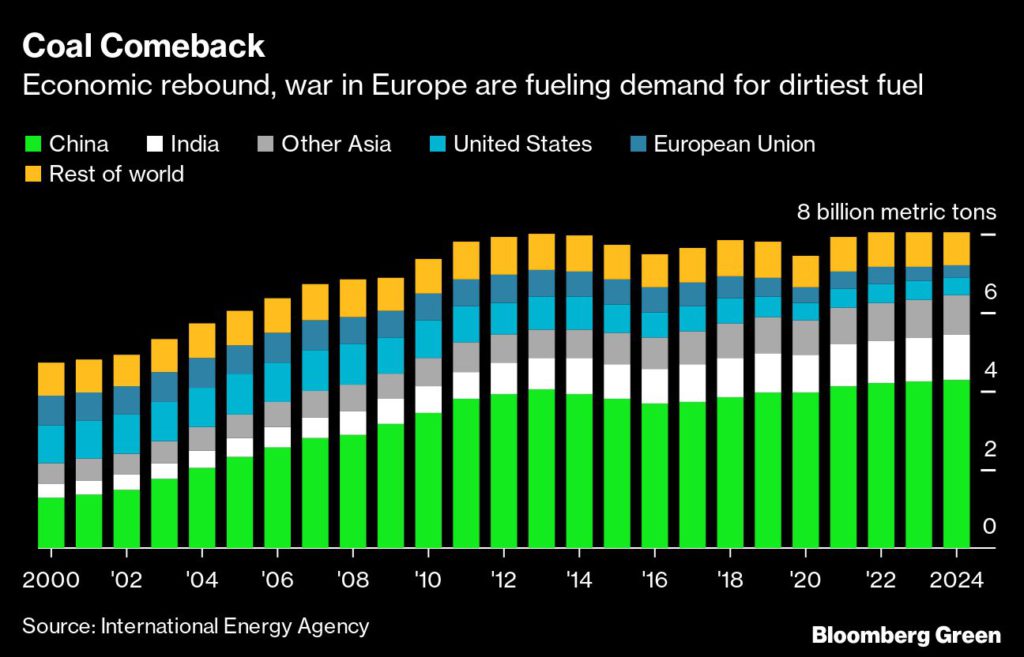

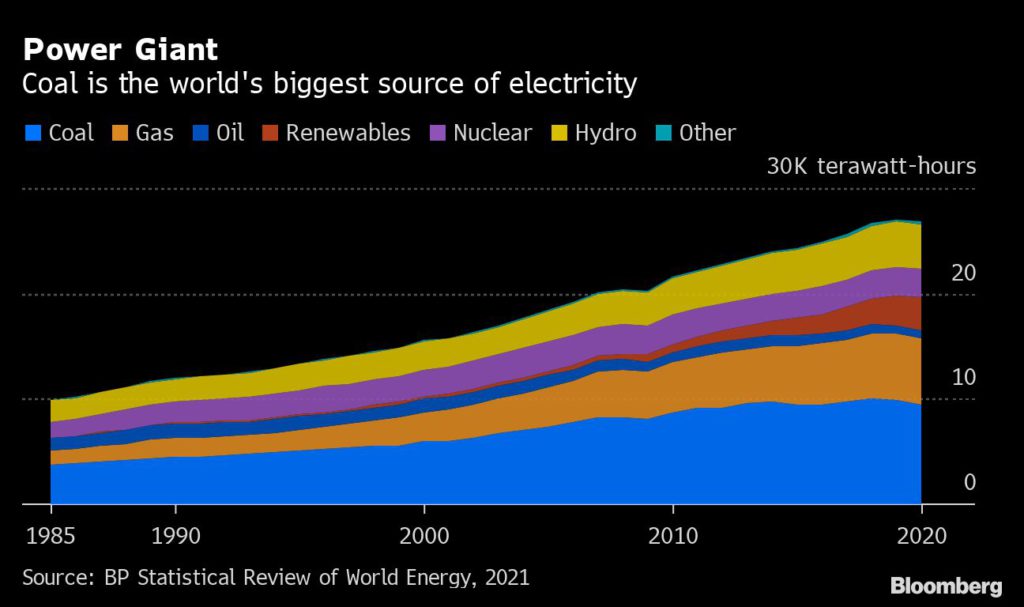

In 2021, the world generated more electricity from coal than ever before, with an increase of 9% from the previous year, according to the International Energy Agency. For 2022, total coal consumption — for generating power, making steel and other industrial uses — is expected to rise by almost 2% to a record of just above 8 billion metric tons and remain there through at least 2024.

“All evidence indicates a widening gap between political ambitions and targets on one side and the realities of the current energy system on the other,” the IEA said, estimating that carbon-dioxide emissions from coal in 2024 will be at least 3 billion tons higher than in a scenario reaching net-zero by 2050.

Coal’s story is inextricably linked with natural gas, often promoted as the cleaner-burning alternative.

Europe’s energy crisis and the coal comeback

As the world began to emerge from the pandemic in mid-2021, power demand surged as stores and factories reopened. But Europe, which had been leading the global charge away from coal, faced an unprecedented crunch for electricity and a shortage of natural gas. At the same time, renewable power was tight in the region and in some other parts other world. The confluence of events sparked blackouts in some regions and sent gas prices to extremes around the world, ushering in the energy crisis.

Suddenly, coal was back in vogue as a less-expensive alternative. Thermal coal, the type burned by power plants, is one of the cheapest fuel sources “on the planet,” with costs at about $15 per million British thermal units, according to a report dated April 1 from Bank of America. That compares with about $25 for crude oil and the global price of $35 for natural gas, the report said.

The European Union, which has some of the world’s most ambitious climate targets, saw its coal use jump 12% last year, the first increase since 2017 — albeit, that gain was from low 2020 levels. Coal consumption climbed 17% in the U.S., and also rose in Asia, Africa and Latin America. India and China, which dominate global markets, were also big drivers for increasing world demand.

Just a few months ago, negotiators arrived in Glasgow for the COP26 climate conference optimistic they could “consign coal to history.”

Instead, the climate talks ended in November with a watering down of the language on the use of coal. China, the U.S. and India are the three biggest polluters, and all three have now pledged to zero-out their emissions in the decades ahead. Yet India and China pursued last-ditch interventions to soften language on coal usage, and the U.S. played a role in accepting that weaker position, calling into question the nations’ short-term commitment to curb coal.

And that was all before the recent further revival for the market.

The IEA issued its annual demand outlook back in December. The agency now plans to issue a mid-year revision in July — its first time ever to do so — to analyze the impact of the war. In all likelihood, demand will be higher than the December forecast as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sets off a chain reaction in the global energy markets that further thrusts coal into the spotlight.

Can the EU give up Russian energy?

Europe is desperate for a way to reduce its reliance on Russia, a key supplier of fossil fuels. The EU is moving to ban Russian coal while also cranking up its overall use of the fuel as it seeks to simultaneously decrease its use of Russian natural gas. Europe’s move is centered on the notion that it will be able to pay more for non-Russian coal supplies than other buyers, a gamble that’s driving up global markets and could price out developing countries that may face shortages.

To help secure energy next winter, the German government is considering working with utilities like RWE AG to reactivate decommissioned coal-fired power plants and delay decommissioning of active facilities.

In Denmark, Orsted A/S is shoring up coal supplies to use instead of biomass, because supplies of the carbon-neutral wood pellets have been disrupted by the war. And Britain is exploring options to bolster energy security, including keeping open Drax Group Plc coal units.

“It’s the last hurrah for coal in Europe,” said Emma Champion, head of regional energy transitions at BloombergNEF.

Even before Europe’s risky move, coal supplies were already precarious. A power plant in Germany had to shut down last year when it ran out of coal. Shortages also led to power outages in India and China, which together account for about two-thirds of global coal consumption.

Coal’s price surge

Prices are hitting stratospheric levels. Futures prices for the Australian benchmark, which rarely breaks $100 a metric ton, spiked to $280 in October as utilities scoured the planet for fuel. It fell back, slightly, as relatively mild winter temperatures in the northern hemisphere eased some demand for power. But when Russia invaded Ukraine, supply concerns drove prices all the way to $440, an all-time high.

Europe’s market followed the same pattern, and even in the U.S., which is driven more by domestic demand, prices reached a 13-year high this month.

“The coal supply chain just wasn’t ready for that kind of shock,” said Xizhou Zhou, managing director for global power and renewables at S&P Global.

As coal grows in importance, supplies are unlikely to follow suit.

Miners are still concerned about long-term demand prospects, especially as the United Nations reiterates its view that the world needs to phase out the fuel. The report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released this month showed that coal burning needs to hit zero by 2050 to reach the goal of limiting global heating to 1.5° Celsius (2.7° Fahrenheit).

“To say in the long run there’s no demand for your product, but in the short run, can you please ramp it up — that’s a lot to ask of a supply chain,” said Ethan Zindler, head of Americas research at BloombergNEF.

Adding to the chaos, policymakers and companies in Japan and South Korea are also making moves to curb Russian coal imports. That will leave even more of the world looking for alternatives to the 187 million tons that Russia exported to power plants last year, which equals about 18% of the world’s thermal coal trade.

It won’t be easy to replace.

Global supply issues

Global production still hasn’t rebounded to pre-pandemic levels. Miners have been hobbled by weather problems, labor shortages and transportation issues, as well as a lack of investment in new capacity.

Indonesia, the top shipper of coal for power stations, halted exports of coal early this year to secure domestic supplies. Producers in Australia, another key exporter, have flagged they have limited ability to raise sales. State-owned Coal India Ltd., the world’s biggest miner, is limiting deliveries to industrial users to prioritize power plants in a bid to avert blackouts for millions of households. Exports from South Africa’s Richards Bay Coal Terminal fell to 58.7 million tons in 2021, the lowest in 25 years.

“The global seaborne coal market remains very tight this year,” said Shirley Zhang, an analyst at Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “So finding alternative supply would be extremely challenging regardless of high prices.”

As global coal supplies tighten and prices rise, emerging-market nations may no longer be able to afford to procure the fuel to keep their economies running. Cash-strapped countries in South Asia, like Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, are particularly exposed to price shocks and are already grappling with energy shortages.

To be sure, if coal’s price surge continues, that could in the longer term further encourage countries to wean themselves off the fuel and replace it with more renewables. And the larger geopolitical tensions brought on by Russia’s war are bolstering the argument that adding more electric vehicles to roads and installing additional wind turbines and solar panels can boost energy independence.

The impact of China’s fuel demand

China is also in the midst of a fossil-fuel production boom. Growing coal output has been an obsession of Beijing’s since a shortage of the fuel caused last year’s widespread power outages.

The nation mines half the world’s coal, and output has been rising just as a recent new spat of pandemic lockdowns slowed economic activity and curbed power demand. But it’s unclear whether the production surges are sustainable, with a top industry official saying recently that the push has reached its limits.

For now, the most-immediate dynamic is a global fight over available coal supplies to avoid power shortages.

“I don’t know if I even have an extra 200 tons,” said Ernie Thrasher, chief executive officer of Xcoal Energy & Resources LLC, the top U.S. exporter. “There physically isn’t the production capacity.”

(By Will Wade and Stephen Stapczynski, with assistance from Paul Burkhardt, Dan Murtaugh, Rajesh Kumar Singh, Eko Listiyorini, Jesper Starn, Todd Gillespie, Will Mathis and Iain Rogers)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Jason

Love it, oh we can’t have pipelines gas is so dirty. Absolutely love it.