Russia is getting frozen out as traders negotiate metals contracts

The metals world is beginning its annual ritual of hashing out contracts for the upcoming year with one key question in many traders’ minds: What’s going to happen to Russian supplies?

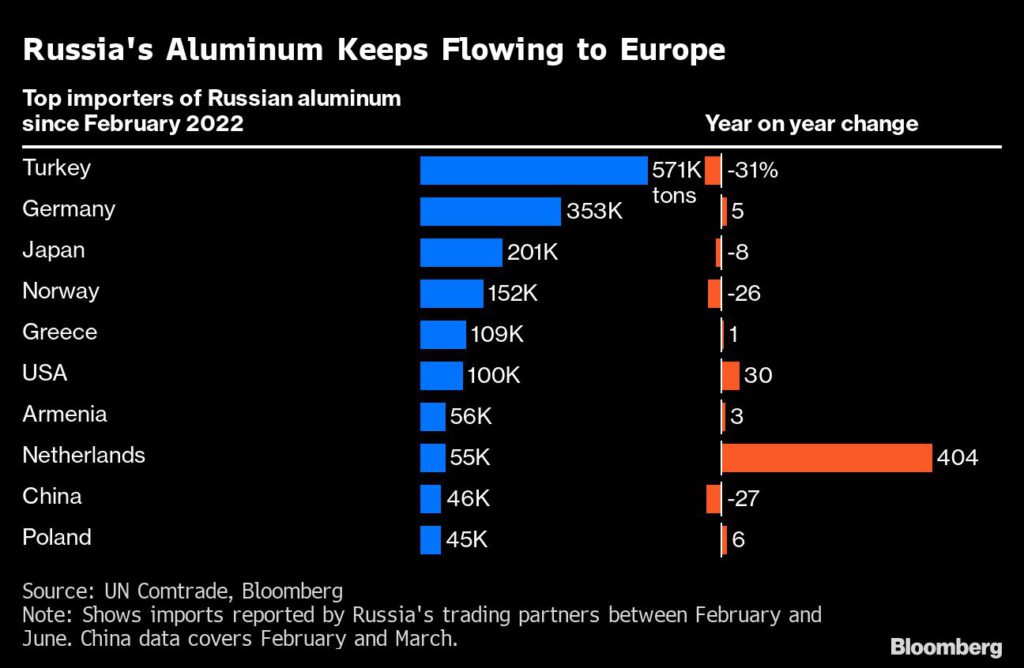

The country is a big producer of aluminum, nickel, copper and palladium, and supply deals signed before the war mean sales have largely kept flowing since the invasion of Ukraine. But September marks the start of what’s known as “mating season,” when new contracts are negotiated, and traders and executives say there’s a growing unwillingness in western manufacturing hubs to receive new Russian metal.

The self sanctioning could disrupt trade dynamics in global metals markets for years, creating schisms between regional markets as those still willing to buy attempt to scoop up Russian metal on the cheap. For aluminum in particular, Europe is usually a key market. Speaking privately, several traders also said they expect significant volumes of Russian aluminum to be dumped on the London Metal Exchange, potentially creating distortions in the global benchmark market.

Norsk Hydro ASA won’t agree to any new Russian metal, while Novelis Inc. has excluded Russian production from a key tender for new contracts to supply its European factories next year. Buyers overall are increasingly pushing back, although some in southern Europe may be more flexible if they can buy at a discount, according to traders involved in the market who asked not to be identified discussing private information.

“We categorically will not be buying from Russia for 2023,” said Paul Warton, executive vice president for Norsk Hydro’s extruded aluminum products business. “I don’t know where that material will flow to now — maybe into Asia, China, Turkey, and other areas that haven’t taken as tough a stance on Russian material.”

There are similar trends in other markets where Russia is the dominant supplier, such as nickel and palladium, but aluminum giant United Co Rusal International PJSC is particularly embedded in the European market and some specialized products vital for carmaking and aviation will be hard to substitute. Aluminum is also the market most vulnerable to growing stockpiles of unwanted Russian metal, because China has plentiful domestic production, making it harder to redirect sales eastward.

The shift from Russia also comes at a time when soaring energy costs are squeezing Europe’s domestic aluminum smelters, although Hydro’s Warton said the industry should be able to plug the gap with alternative supplies, such as imports from the Middle East.

Neither Rusal nor nickel and palladium giant MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC have been sanctioned by the U.S. or Europe.

And while some large buyers are balking, Rusal is planning to keep large shipments flowing to Glencore Plc under a multiyear supply deal that it signed in 2020, according to people familiar with the matter.

For Nornickel, early discussions with customers suggest that European buyers will try to reduce purchases, according to a person familiar with the matter. It’s too early to estimate how big the effect will be, the person said. The company’s large share of global production means its metals are hard to replace, although the miner is prepared to shift some sales eastward.

Spokespeople for Rusal and Nornickel didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment. Glencore declined to comment.

The question of Russian metal also remains a key focus for the London Metal Exchange and its members, according to people familiar with the matter. The exchange doesn’t plan to take independent action against Russian suppliers outside the scope of government sanctions, but is keeping the situation under review, a spokesperson said.

Excess stocks

If Rusal’s sales do drop sharply in Europe, the producer may offload excess stocks onto the exchange. Such a move could put further pressure on prices and — if the bourse becomes a dumping ground for metal that industrial consumers don’t want to touch — could force it to reassess its stance.

The LME is looking closely at the issue and it is a regular subject of discussion at meetings of the board and metal committees, one of the people said.

“If the demand isn’t there to absorb production then you will be likely to see more deliveries into the LME system,” Nicholas Snowdon, an analyst at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., said at a Fastmarkets aluminum conference in Barcelona. In the context of softer market conditions, self-sanctioning also “increases the likelihood of further deliveries,” he said.

As contractual discussions get underway, the metals industry also needs to weigh the outlook for weaker demand amid global economic gloom, against tightening supply in Europe, where high energy prices have forced smelters to cut back and even halt production.

A key part of the negotiations for deals will be the delivery surcharges that contractual customers agree to pay over futures prices for metal delivered to local ports, and traders are bracing for a big drop. European suppliers say they’re optimistic that the mounting aversion to Russian metal will give them an advantage premiums, while Rusal may need to offer discounts on its delivery premiums to entice buyers.

(By Mark Burton, Archie Hunter and Jack Farchy)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments